After nearly four decades, the bipartisan coalition that pushed higher standards, tests, and accountability systems to improve public education has fractured. While standards-based reform lifted student achievement, especially for Black and Hispanic students who had long been marginalized in American education, it also generated a backlash against what critics charged were a preoccupation with test scores and an overly punitive stance toward teachers and schools.

But a nascent movement to expand students’ opportunities to acquire critical knowledge, skills and social networks by abandoning a “bachelor’s degree or bust” mentality in favor of multiple pathways to opportunity based on students’ passions and purposes could forge the next bipartisan consensus on education.

This new opportunity agenda differs sharply from vocational education of old that placed students into different tracks and occupational destinations based mostly on family background. That sorting process often carried with it racial, ethnic, and social-class biases, with immigrant students, low-income students, and students of color typically enrolled in low-level academic and vocational training and middle- and upper-class White students enrolled in academic, college-preparatory classes. Educators often described vocational programs as dumping grounds for students thought incapable of doing serious academic work, as Jeannie Oakes and her colleagues at the RAND Corporation found in their seminal 1992 report Educational Matchmaking.

In contrast, the new career pathways emerging around the country exemplify what University of Texas law professor Joseph Fishkin calls opportunity pluralism, a move to make the nation’s opportunity infrastructure more pluralistic by offering individuals more pathways to success.

A confluence of factors is fueling the new opportunity agenda. The rising cost of a college degree is leading many students to think they cannot afford college despite research showing that college graduates earn far more over their lifetimes than nongraduates. An increasing number of well-paying jobs do not require a bachelor’s degree but do require technical skills and credentials beyond high school. And the science of learning and development has emphasized the need to broaden education’s focus beyond academics to incorporate young people’s social-emotional development, including their search for identity, belonging, and agency.

The need to rethink the connection between K-12 education and careers garners strong support from parents and young people. In a recent nationally representative survey of public and private school parents conducted by FIL Inc., two out of three would rethink “how we educate students, coming up with new ways to teach children.” Eighty-two percent favor “work-based learning programs or apprenticeships in various career fields” and 80 percent support “more vocational classes in high schools.”

For their part, the nation’s more than 72 million young adults born between 1981 and 1996 express a sense of buyer’s remorse about their high school educations: Only some 22 percent say high school prepared them for workforce success.

II

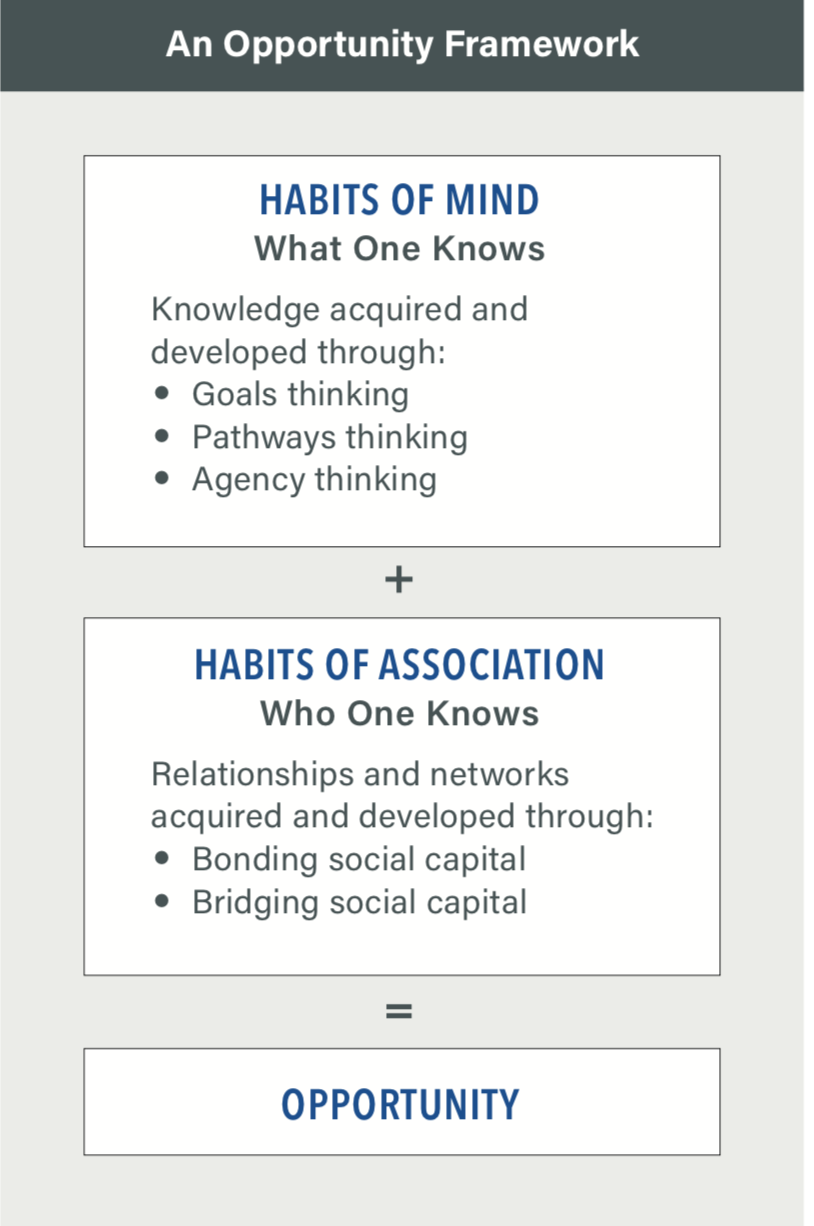

The essential elements of the opportunity agenda are what students know (knowledge) and whom they know (relationships.) Beyond the acquisition of academic and technical skills, students also need to cultivate other habits of mind and associations as the building blocks of individual opportunity. We call them habits because pursuing knowledge and relationships requires behaviors learned and internalized through practice. These habits are also character strengths that lead to the building of democratic, civic communities. Together, they enable the pursuit of opportunity.

Habits of mind comprise three types of thinking: goals thinking (defining and setting achievable outcomes); pathways thinking (creating a route to these outcomes); and agency thinking (pursuing goals and pathways through personal agency and self-efficacy). Pathways and agency thinking together foster the pursuit of goals, helping students overcome life obstacles.

Habits of mind comprise three types of thinking: goals thinking (defining and setting achievable outcomes); pathways thinking (creating a route to these outcomes); and agency thinking (pursuing goals and pathways through personal agency and self-efficacy). Pathways and agency thinking together foster the pursuit of goals, helping students overcome life obstacles.

Habits of association include two kinds of social capital networks: “bonding” and “bridging.” Bonding social capital occurs within a group, reflecting the need to be with others for emotional support and companionship. Bridging social capital occurs between social groups, reflecting the need to connect with individuals different than ourselves, expanding our social circles across demographics and interests.

Bonding and bridging social capital are complementary. As social scientist Xavier de Souza Briggs notes, binding social capital is for “getting by,” and bridging social capital is for “getting ahead.”

Economist Glenn C. Loury suggests that social capital may be an essential prerequisite for creating what economists call human capital, the experiences, skills, training, education, and acquired social aptitudes that determine individuals’ earning power and, thus, their ability to generate and accumulate wealth.

Social capital operates on multiple levels: the relationships between individuals, such as between young people and prospective employers; the relationships with mid-level groups or firms, such as between young people and local community organizations; and the relationships with courts and other large local and national institutions that order society and that we often think of as civic capital. In short, opportunity equals knowledge plus an ever-expanding set of networks that center young people in society.

Understanding opportunity through a prism of knowledge and networks is a way to frame a bipartisan conversation about the role of schools and other community institutions in student success. It has the potential to unite divergent political orientations and beliefs by encouraging and enabling individuals, schools, community organizations and local enterprises to work together—expanding their relationships, networks, and social circles to advance opportunity and engendering an understanding of relationships as valuable resources.

III

Today’s opaque education credentialing process for work and careers too often serves as a bottleneck, rather than a bridge, to opportunity for young people. As a result, young people have different levels of confidence in their ability to set occupational goals and develop pathways to reach them. Young people from households with lower incomes, in particular, report feeling more pressured to make premature occupational choices in part because of the financial risks associated with longer periods of education and career exploration. Black and Hispanic young people understand the impact supportive adults can have in their lives but don’t always know where or how to find them.

To ensure that young people are empowered to choose the pathways and connections that are right for them, the new opportunity agenda recognizes that students need:

Academics + Technical Skills. The new opportunity agenda builds on the history of standards-based reform by recognizing that all young people need a strong foundation of academic skills—but they also need the opportunity to begin acquiring technical skills in high school that can give them a jump start on careers.

Credentials + Networks. Although equalizing opportunity along the pathway from high school graduation to a bachelor’s degree remains an important policy goal, the new opportunity agenda focuses on the creation of multiple pathways to success through the acquisition of credentials that are valued in the labor market and that young people can begin earning in high school.

These credentials should both certify young people’s employability based on key skill sets and serve as building blocks toward associate’s and bachelor’s degrees, through the expansion of such pathways as dual-enrollment programs and early college high schools.

Equally important is connecting young people with adults who can serve as mentors and bridge builders to viable careers. This is particularly important for young people in high-poverty communities who may lack connections to adults in their chosen career fields.

Agency + Advising. To avoid tracking young people into jobs based on race, ethnicity, gender, and social class, the new opportunity agenda must include a strong system of advising and early career exploration so that young people are knowledgeable and empowered to choose the pathways that are right for them, rather than having pathways chosen for them.

[Read More: Pathway Models]

These principles lead to five essential features of pathways programs that can guide coalition efforts at the local and state levels:

Academic Core and a Credential. Programs have a clear curriculum that combines academic and technical skills and is aligned with labor market needs—i.e., supply and demand are linked. There is a well-defined timeline for program completion. Upon completion, participants receive a recognized career credential. In the best of circumstances, there is a good job waiting for the program graduate.

Exposure to Work and Careers. Programs are structured to introduce young people to work and careers no later than middle school, through activities like guest speakers and field trips. High school includes career exposure through work placement, including mentorships and internships. Work-based learning is integrated into classroom instruction. It is also used as a motivational strategy challenging young people with genuine tasks so they understand labor market demands—both academic and technical knowledge and “soft skills” like the ability to communicate clearly through writing and speaking.

A Strong System of Advising. Programs include a robust advisory component to ensure that students are making informed choices about their chosen pathways; address potential barriers, such as financial assistance; and use data to keep students on track to their goals.

Authentic Partnerships. Employers, industry associations, and other local institutions collaborate in this effort. Employers help set program standards and define skills and competencies needed for certification and employment and provide paid apprenticeships. Others assist with convening, planning, and work placement navigation and social support services for participants (and their families). There are written agreements between partners that delineate roles and responsibilities. They include budgets.

Supporting Policies. Policy leaders play a critical role in these programs, since local, state, and federal policies create a framework for the programs’ development and expansion. The policy framework includes executive orders and federal, state, and local directives. For example, a policy that creates incentives for K-12, postsecondary institutions, labor, and workforce groups to integrate their funding streams enables long-term financial support for pathways programs.

Together, these elements of successful pathway programs help young people develop an occupational identityand a vocational self, as well as a broader sense of who they are as adults, something that should be a key focus of schools preparing young people for civic responsibility.

IV

Importantly, the opportunity agenda requires a shift away from traditional notions of success centered on advanced degrees, status, and wealth. And there’s evidence that that is happening.

In 2019, Gallup and the think tank Populace conducted wide-ranging interviews and a survey with a nationally representative sample of 5,242 adults to create The Success Index, a portrait of what success means to Americans. In the course of their interviews, they learned that while many individuals believe society’s view of success is based on wealth and status, their personal definition of success is rooted in happiness, peace of mind, and a fulfilling life. They balanced education, work, and financial security with health, character, and the quality of personal relationships. Eighty-eight percent of respondents prioritized a “good, satisfying life” over a “successful life by society’s definition.”

A recent poll by Echelon Insights conducted for the Walton Family Foundation of Gen Z (ages 13 to 23) and Millennials (ages 24 to 39) on the American Dream and how they think about their futures yielded a similar perspective. Both groups described the dream as having the freedom and opportunity to build their lives on their own terms, having many paths to success.

Similarly, nearly 4,000 Black and Hispanic youth from all income levels and White youth from households with annual incomes less than $75,000 reported to Goodwin Simon Strategic Research that they aspire to a career that is fulfilling. They want to be well-connected and respected socially. And they want to give back to their communities. They see themselves as change agents but know they need connections and relationships to realize their goals.

On the employer side of the equation, the Center on Education and the Workforce at Georgetown University and the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland have identified growing numbers of jobs that require more than a high school diploma but less than a bachelor’s degree. This middle-skills sector, where traditional blue-collar jobs are increasingly being replaced by skilled technical work, now represents nearly a quarter of all employment paying at least $35,000 a year.

Helping young people achieve their aspirations by making the nation’s opportunity infrastructure more pluralistic, by providing young people with a greater range of pathways to pursue the knowledge and networks they need to achieve their aspirations and live flourishing lives, is an agenda for conservatives, moderates and liberals alike.

It offers a chance to put aside the divisive school reform debates of recent years and forge new and diverse coalitions of policymakers, advocates, funders and other civic entrepreneurs. It is, ultimately, a new civic equation that gives the nation’s schools a key role in building new pathways to the future.

Bruno Manno is a senior advisor to the K-12 program at the Walton Family Foundation. Lynn Olson is principal at Lynn Olson LLC and a FutureEd senior fellow.

The Walton Family Foundation supports FutureEd financially.