Put yourself in the shoes of a state or school district education leader about to receive a share of hundreds of billions of dollars from the American Rescue Act, the largest infusion of federal education funding in history. Which schools and grades could use the most support? As you chart a path to allocate these funds before they expire in 2024, how can you and your constituents monitor educational progress?

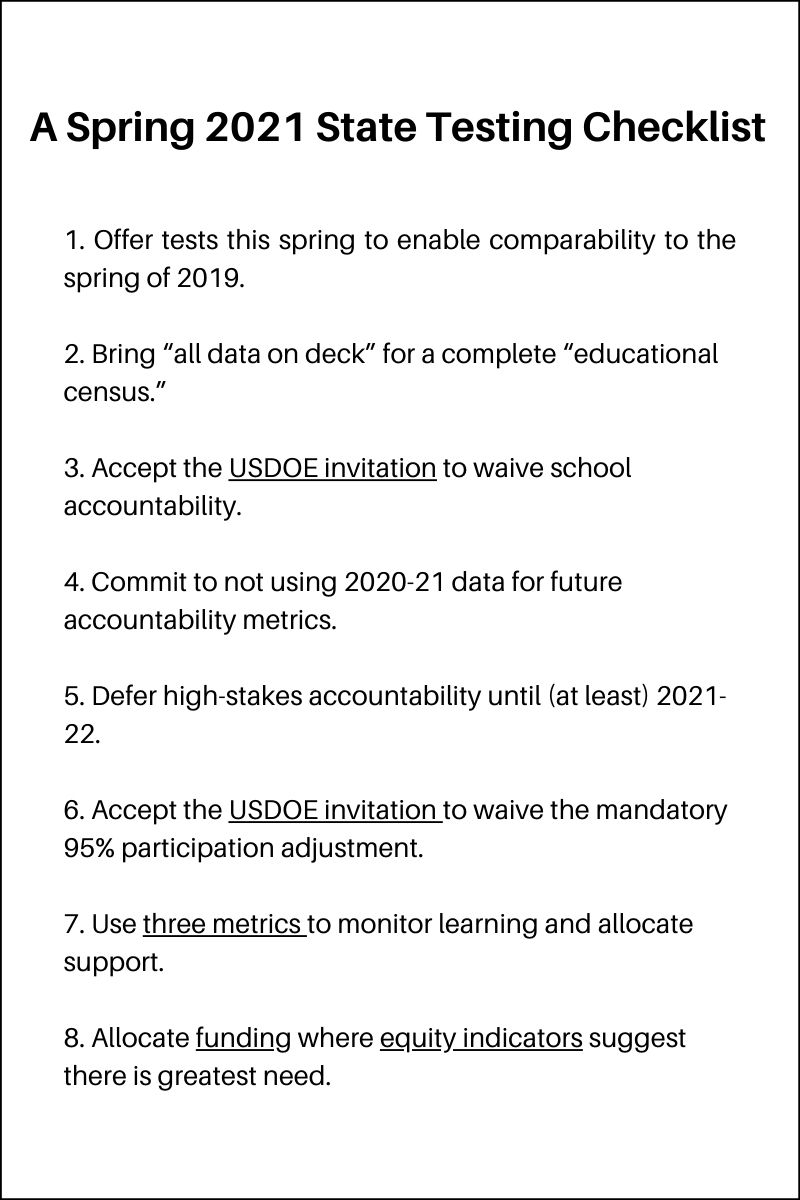

State standardized tests are ideally suited for this purpose. Yet many state and district leaders are asking for waivers from testing this spring, arguing that testing is unnecessary, infeasible, and even inhumane.

I can see why. While tests could diagnose needs and direct effective interventions, 20-plus years of education policy have cast testing as a tool for unforgiving accountability. Stories of failure dominate stories of improvement. Achievement gap rhetoric can reinforce racist and classist ideas that low-scoring students have irrevocable deficits. State tests have lost the support of many students, parents, teachers, and school leaders.

The lingering mistrust and doubt are understandable. Without specific answers to the questions of how states and districts will use test scores to target support, education professionals may assume that testing is just a ploy to get back to the same old accountability blame-game, to set a new baseline for the next value-added model.

It is an unfortunate coincidence that this oft-deserved backlash is culminating in a political movement to waive state tests just when these tests could help policymakers direct federal Covid relief aid effectively. And this could be accomplished without forcing children to take standardized tests or holding schools accountable for test results.

Testing is necessary, feasible, and, if flexible, humane. Especially if it is part of an “educational census” that brings “all data on deck”—information on students’ academic achievement, but also their physical and emotional health, attendance records, and other equity indicators—to help ensure that students who need the most help get it. State tests have three particular strengths that make them valuable this spring above and beyond classroom and district assessments that provide timely feedback: comparability, alignment, and authority.

[Read More: Blueprint for Testing: How Schools Should Assess Students During the Covid Crisis]

State standardized tests have strong quality controls that enable experts to compare student results across schools and school districts and over time. Comparability over time enables leaders to target resources not only to schools, grades, and subpopulations that needed support in 2019, but also those who now need even more support in the wake of the pandemic.

Second, state tests are designed to measure consensus content standards more directly than district and local alternatives. Although some states have suggested that district tests will suffice, there is not sufficient evidence to support “equating” of district and state tests.

Third, state tests have credible performance standards, selected by consensus among teachers and subject matter experts in each state. These standards can highlight disparities and inequities with the greatest authority. Together, the comparability, alignment, and authority of state tests enable us to answer a critical question that other tests cannot: Where have our needs grown greatest?

But states must change their business-as-usual score reporting. Failure to do so will cripple the validity of the results by conflating changes in student populations with changes in student proficiency. A school that has an out-migration of previously high-scoring students will look like it needs disproportionate assistance when it does not. A school that has an out-migration of low-scoring students will look like it does not need assistance when it desperately does.

This year, unlike a typical year when almost all students are in school, we must pay attention to both students who are tested, and those who are not. This can be accomplished by considering three metrics instead of one: a “fair trend,” an “equity check,” and a “match rate.” Like a blood pressure reading that provides two useful numbers, these multiple metrics provide a necessarily complete assessment of school needs while accommodating absences, departures, and students who opt out.

The “fair trend” captures the progress of 2021 test takers by comparing their results to their own past scores. The “equity check” describes the scores of students who are not tested in 2021 by looking at their past scores. The “match rate” describes the relative weight of the two. If there is no testing this spring, educators are essentially left with only an “equity check” with no “fair trend.”

All states should calculate these metrics, even those who believe that they will have high attendance rates. Standard attendance rates may dramatically underestimate student absenteeism, by neglecting students who would be in school but for the pandemic. These students should be included in the “equity check” in the hopes that they’ll return to school rolls soon.

Students and parents who want to test should be able to test, to know where they stand and help to allocate additional support. Students and parents for whom testing would be stressful or unsafe should be able to opt out. But the greater the number of students who are tested, the better we will be able to allocate support where it is most needed.

To build trust among teachers, parents and students, states should take the Department of Education’s invitation for an accountability waiver. States should additionally commit that 2020-21 data will not be repurposed inappropriately for accountability metrics in the future.

This is a year when we should hold educators harmless and focus on student need. States should opt-out of accountability and opt-in to smart metrics for state testing.