In his State of the Union address, President Joe Biden called on local educators to use their federal Covid-relief aid for tutoring programs that can support students who have fallen behind academically. “I urge every parent to make sure your school does just that,” Biden said in the March 1 speech. “They have the money. We can all play a part: sign up to be a tutor or a mentor.”

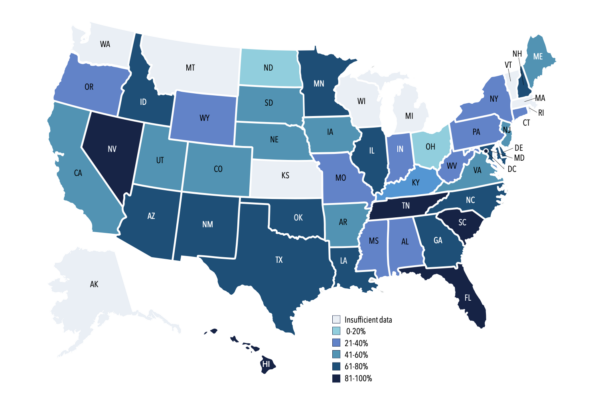

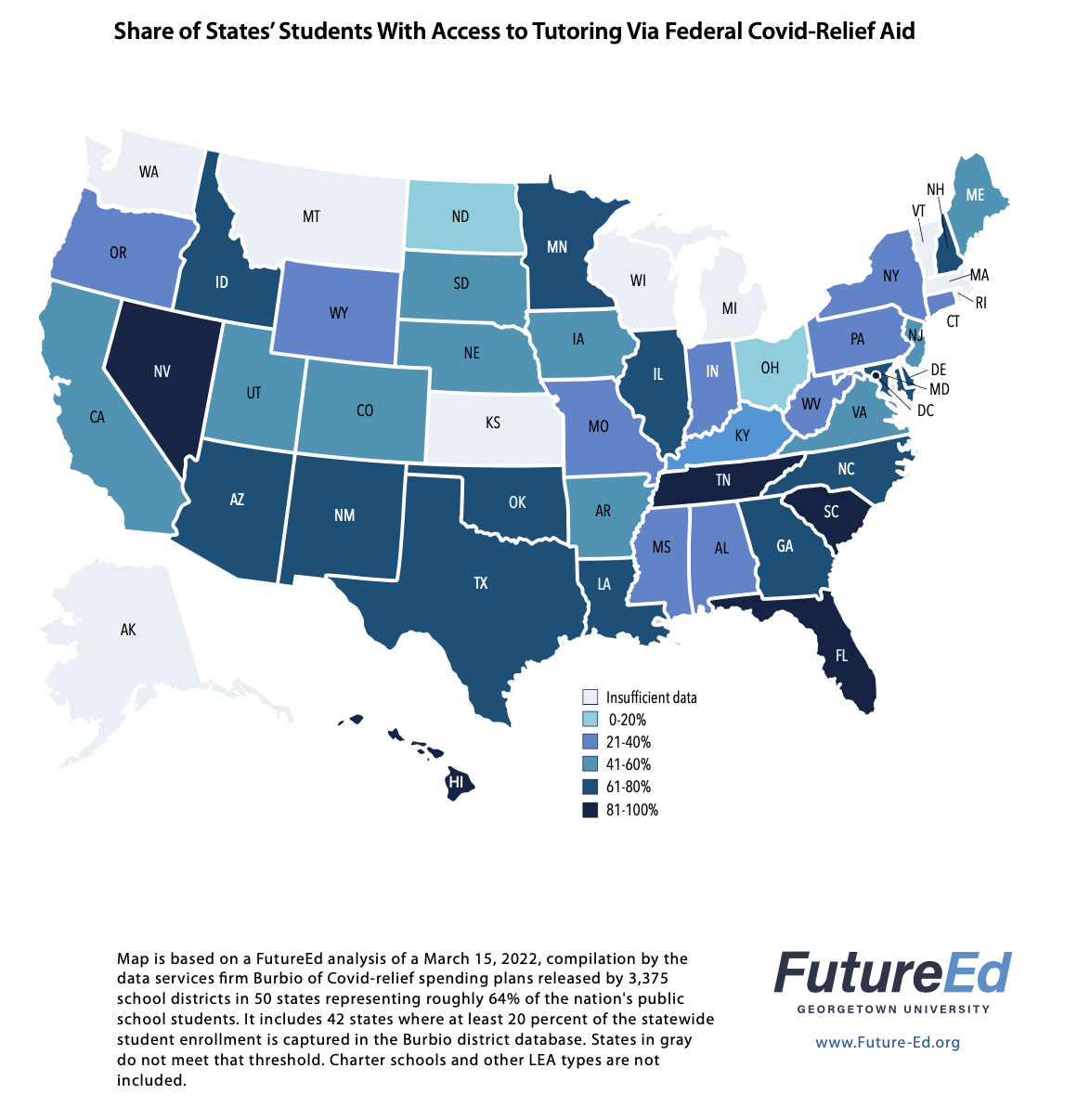

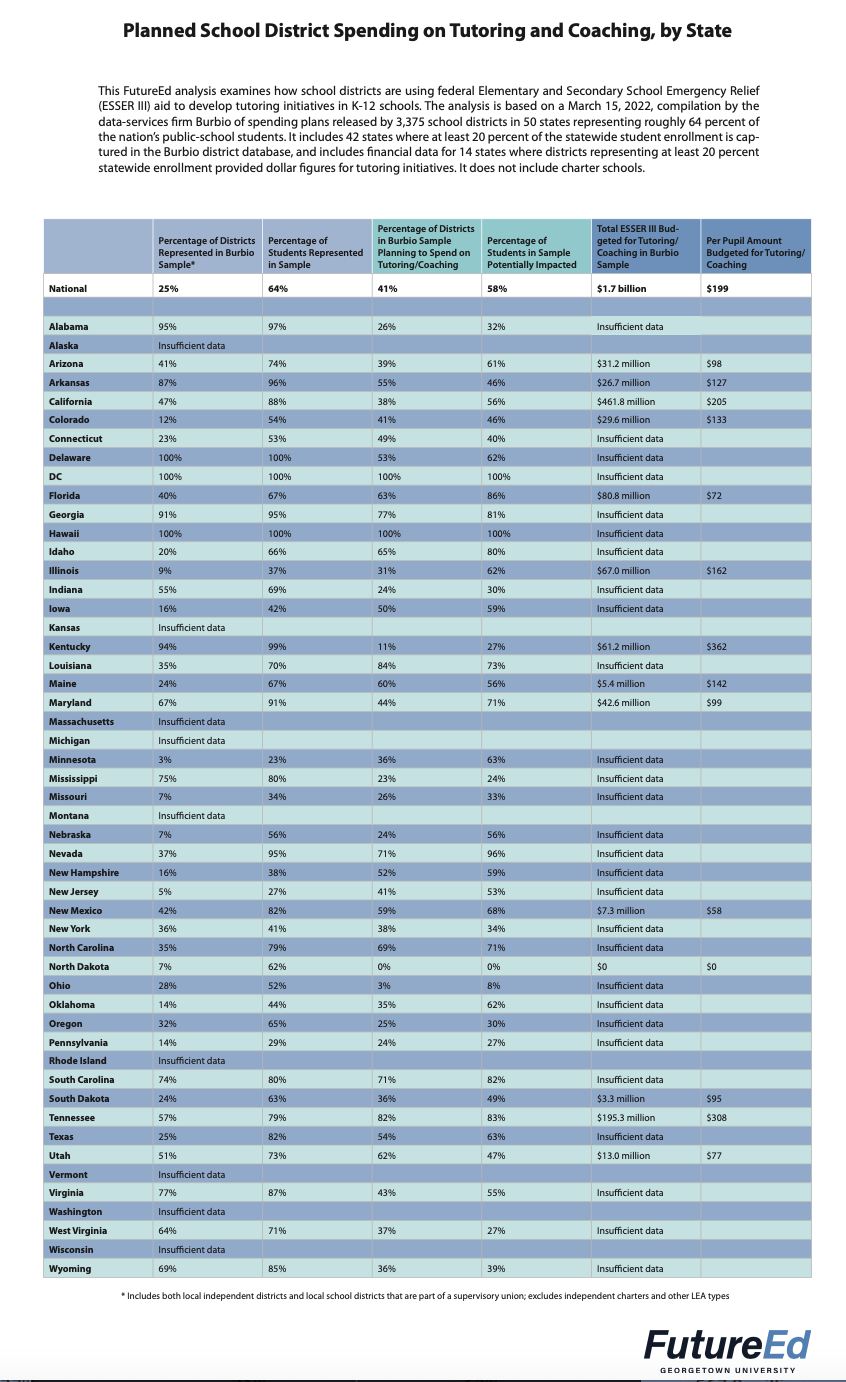

A new FutureEd analysis suggests that more than 40 percent of school districts and charter organizations—and two-thirds of the nation’s largest systems—are planning to put a portion of their federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER III) money toward tutoring and academic coaching.

And America Achieves announced that it has raised $65 million in philanthropy to launch a new national nonprofit organization to support the expansion of high-quality tutoring systems in the nation’s schools. Former Tennessee Commissioner of Education Kevin Huffman will lead the initiative, known as Accelerate.

Using a database of Covid-spending plans released by more than 3,500 local education agencies compiled by the Burbio data services firm, FutureEd estimates that more than $1.7 billion has been designated for tutoring and coaching by school districts in the sample, with roughly $24 million more committed by charter organizations and other LEAs.

That’s about 3.3 percent of the $53 billion that these districts have designated for spending so far. Since the sample is roughly nationally representative*, spending on these priorities could reach $3.6 billion in school districts nationwide by the time the money is fully spent in late 2024.

The sum is likely even larger since some districts haven’t yet assigned dollar figures to their tutoring initiatives. Others are building tutoring into summer or afterschool programs, which appear in different line items in local spending plans. Some districts use the terms tutoring and academic coaching interchangeably, but coaching is more likely to refer to personalized support from an instructional specialist during the school day.

In addition to local investments, 37 state education agencies support tutoring programs in their own ESSER spending plans, including grants to local districts and statewide tutoring corps in Tennessee and Arkansas. State education agencies can spend up to 10 percent of the ESSER III money, $12 billion of the $122 billion allotted by Congress.

Research shows that well-designed tutoring is one of the most effective interventions for helping students catch up on learning, making it a valuable tool in the wake of the pandemic. But schools face several key challenges to expanding tutoring and coaching for students.

The first is staffing: many districts simply can’t find the tutors they need to help all those who have fallen behind. A second is student attendance: absenteeism rates remain high across the country, and even students who attend during the school day often eschew afterschool help sessions. A third challenge is designing tutoring programs with research-based features that make a difference for student learning, including offering services at least three times a week with no more than four students per tutor.

[Read More: State Guidance for High-Impact Tutoring]

At this point, the plans represent what districts hope to spend, rather than what they have actually spent. But they provide a sense of how districts will deliver tutoring and coaching services. FutureEd reviewed plans for the nation’s 100 largest school districts, which educate 22 percent of the nation’s students and account for more than $1 billion in spending on tutoring and coaching. We found that:

- Large districts plan to offer tutoring at a range of times: during the school day, before school, in afterschool programs, and in Saturday schools.

- Many districts are focusing on literacy tutoring in the elementary grades and math skills for middle and high school students. This jibes with research finding that the biggest gains for younger students are in literacy. New York City, for instance, is including tutoring as part of its Early Literacy for All initiative, which also includes screening for dyslexia. Seattle is focusing on students identified with special needs. Houston is including tutoring for college entrance exams within a broader initiative.

- Districts are drawing on tutors from a range of sources, tapping existing staff, college students, volunteers, and community organizations. Several districts are using national service workers provided through AmeriCorps.

The plans reveal some innovative approaches: Chicago, for instance, is forming a tutoring corps using both internal staff and tutors hired and trained from the community, local universities, and a pool of recent high school graduates. Pinellas County, Fla., is supplementing its more traditional approaches led by teachers with a peer-to-peer tutoring corps. The Baltimore City school district is tapping paraeducators and using the tutoring sessions as an opportunity not only to help students catch up, but also to develop paraeducators’ skills toward eventually becoming teachers. Washoe County, Nev., which includes Reno, is hiring long-term substitute teachers who can serve as tutors when they’re not teaching a class.

In Tennessee, state officials are driving local commitment to tutoring. Using the state’s share of earlier rounds of federal Covid-relief funding and other resources, Tennessee has earmarked an estimated $200 million for the Tennessee Accelerating Literacy and Learning (TN ALL) Corps. The state initiative, established by the Tennessee legislature, recruits tutors, develops content for lessons, and provides matching grants to local education agencies.

[Read More: Smart State Strategies Building for Intensive Tutoring Systems]

The state set evidence-based standards for the program, including requiring that students receive at least two sessions a week for 30 to 45 minutes each, with no more than three students in elementary school and four in middle school working with a tutor at one time. At this point, 82 percent of Tennessee’s school districts in the Burbio sample have signed on for the initiative, and they expect to spend $195 million on tutoring programs, about $308 per student. An analysis by Tennessee SCORE suggests that about half the districts they reviewed are using evidence-based practices.

In Arkansas, another state with a tutoring corps, more than half the districts in the sample plan to spend on tutoring and coaching. Their expected expenditures add up to nearly $27 million, or about $127 per student. More than a third of California’s districts in the sample are investing in these priorities for a total of $462 million, or about $205 per student.

In Louisiana, where the state education agency launched a tutoring strategy known as Accelerate, about 84 percent of school districts in the Burbio sample are planning to offer tutoring and coaching. Most of them, though, do not provide dollar figures for how much they intend to spend. Georgia, likewise, has nearly 80 percent of its districts planning to do tutoring, but the state didn’t ask for a breakdown on spending for that priority in its local plan template.

The widespread investment in tutoring is a welcome sign that districts and states recognize the value of the intervention in helping students recover academically. The challenge ahead is to ensure that schools are using evidence-based practices and implementing them effectively.

*The Burbio sample is somewhat overweighted toward large, urban districts, although the demographic characteristics of the student population in the sample are otherwise similar to nationwide trends, meeting the U.S. Education Department’s standards for a representative sample. It includes only 4 percent of the nation’s charter school organizations and 14 percent of charter students.

FutureEd research associates Nathan Kriha, Gunjan Maheshwari and Robert Nishimwe and communications associates Andrew Edghill and Noa Neubia contributed to this report.