FutureEd was invited to testify before the Early Childhood, Elementary, and Secondary Education Subcommittee of the House Education & Labor Committee at its September 20, 2022, hearing: Back to School: Meeting Students’ Academic, Social, and Emotional Needs. Below is the written testimony we submitted, as well as a videoclip of testimony for associate director Phyllis Jordan.

We are honored to be here today to discuss the learning loss that students have experienced during the pandemic and the plans that school districts and states have developed for spending federal Covid-relief aid, particularly the $122 billion allotted for K-12 schools in the American Rescue Plan, to help students recover academically and socially. Our research into 5,000 school districts has shown that local educators have set priorities for spending most of the federal aid they have received and are beginning to spend that money in anticipation of the September 2024 deadline for obligating the funds.

While there is concern that the spending in some places has been slow, we are beginning to see promising practices that suggest this unprecedented infusion of federal cash will make a difference for students and schools. These positive signs include a renewed commitment to following the science when we teach reading, the use of targeted financial incentives to address teacher shortages, increased support for accelerating learning through tutoring, and a long overdue recognition of the importance of students’ mental health and emotional well-being to their academic success.

Learning Loss and its Solutions

The impact of the pandemic on learning is clear: National Assessment of Educational Progress data released earlier this month showed that between 2020 and 2022, reading scores for 9-year-olds fell by 5 points, the largest drop in over 30 years. In math, scores fell 7, the first drop ever since the test began in 1970s. The declines were greatest among the students already struggling in school and among students from low-income families, widening achievement gaps and creating more challenges for our schools. Other national and state studies suggest students showed some recovery in the past school year, but there is still substantial work to do. A study released in May led by researchers Dan Goldhaber and Tom Kane found that students who spent more time learning remotely experienced bigger learning gaps than those who returned to school sooner,. Beyond the academic indicators, schools saw absenteeism rise over the past year and student engagement decline. Many students experienced anxiety and depression, and teachers felt stressed out and stretched thin.

But just as the impact on student learning is clear, so are the solutions. A body of research points educators to interventions that can help students recover academically and socially. We’re seeing school districts adopt these solutions in their plans for spending the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER III) aid included in the American Rescue Plan.

In our Covid Relief Playbook, released in June 2021, FutureEd highlighted 18 evidence-based practices that have delivered improvements in instructional quality, school climate, student attendance, or student achievement—and sometimes all four.

Among the most common we see in ESSER III plans are:

Tutoring: High-impact tutoring can boost academic achievement, social-emotional development, and other outcomes. While tutoring can take many forms and often includes a mentoring component, Brown University’s National Student Support Accelerator defines high-impact tutoring as “a form of teaching, one-on-one or in a small group, toward a specific goal” that supplements, but does not replace, classroom instruction. Tutoring is most effective when it: occurs during the regular school day; includes at least three sessions per week for the duration of the school year; occurs in groups of four or fewer students; has students work with the same tutor over time; provides tutors with pre-service training, oversight, ongoing coaching, and clear lines of accountability; uses data to inform tutoring sessions; uses materials aligned with research and state standards.

Summer Learning: Research shows that well-designed summer programs lead to gains in reading and math and support the social-emotional development of students when students attend regularly. A study of several programs by the RAND Corporation suggests that the most effective summer programs run for at least five weeks, preferably six, and provide at least three hours a day of academic instruction—a standard few districts currently meet. Students who attend at least 80 percent of the summer classes and return in subsequent summers achieve the best results. Many successful programs combine academic with enrichment activities, often in partnership with community organizations.

Afterschool Programs: Researchers have found that regular participation in afterschool programs was associated with gains in math achievement test scores for elementary and middle school students over two years, when compared to students who dropped into programming but were not consistently supervised. Elementary and middle school students who regularly. Afterschool programs serving 10 to 20 students and offering 70 to 130 hours of additional instructional time annually are most effective, but programs that offer 44 to 100 hours annually are also likely to have an impact.

The ARP explicitly calls for districts to use evidence-based practices, using the four levels of evidence described in the federal Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). Strong evidence requires randomly assigning groups of similar students to receive an intervention while other students continue as usual. Moderate evidence involves research comparing similar groups but no random assignment. Both of these levels must involve at least 350 students across several sites. Promising evidence provides a correlation to positive results but lacks either similar comparison groups or the size of the stronger research. Finally, ESSA and ARP, allow districts to use a lower level of evidence, which has no research yet but offers a rationale that the intervention can yield positive results. In some cases, the intervention may be too new to have the support of rigorous study, though there may be evidence from a similar study to suggest the approach might work. These four levels of evidence give schools and districts wide latitude to adopt interventions that can help students recover academically and socially from the damage done by the pandemic. Implemented effectively, these proven practices can provide substantial returns on state and local Covid-relief investments.

Trends in Spending ESSER III Funds.

Plans and Priorities

When it comes to Covid-relief spending, there are three key questions we need to answer. The first is how do districts and charter organizations plan to spend this unprecedented infusion of federal money to address learning loss? That’s a question on which we have quite a bit of information to share. The second question is what actual spending looks like, both in terms of how quickly districts are spending and whether they’re staying true to their plans? The answer is starting to emerge, but it’s incomplete. The third question, and probably most important, what will the impact of this investment be on student achievement? It’s early, but we’re seeing some promising signs that this evidence-based work is helping with academic recovery and that states and districts are spending some of the federal money to provide proof points on what is effective.

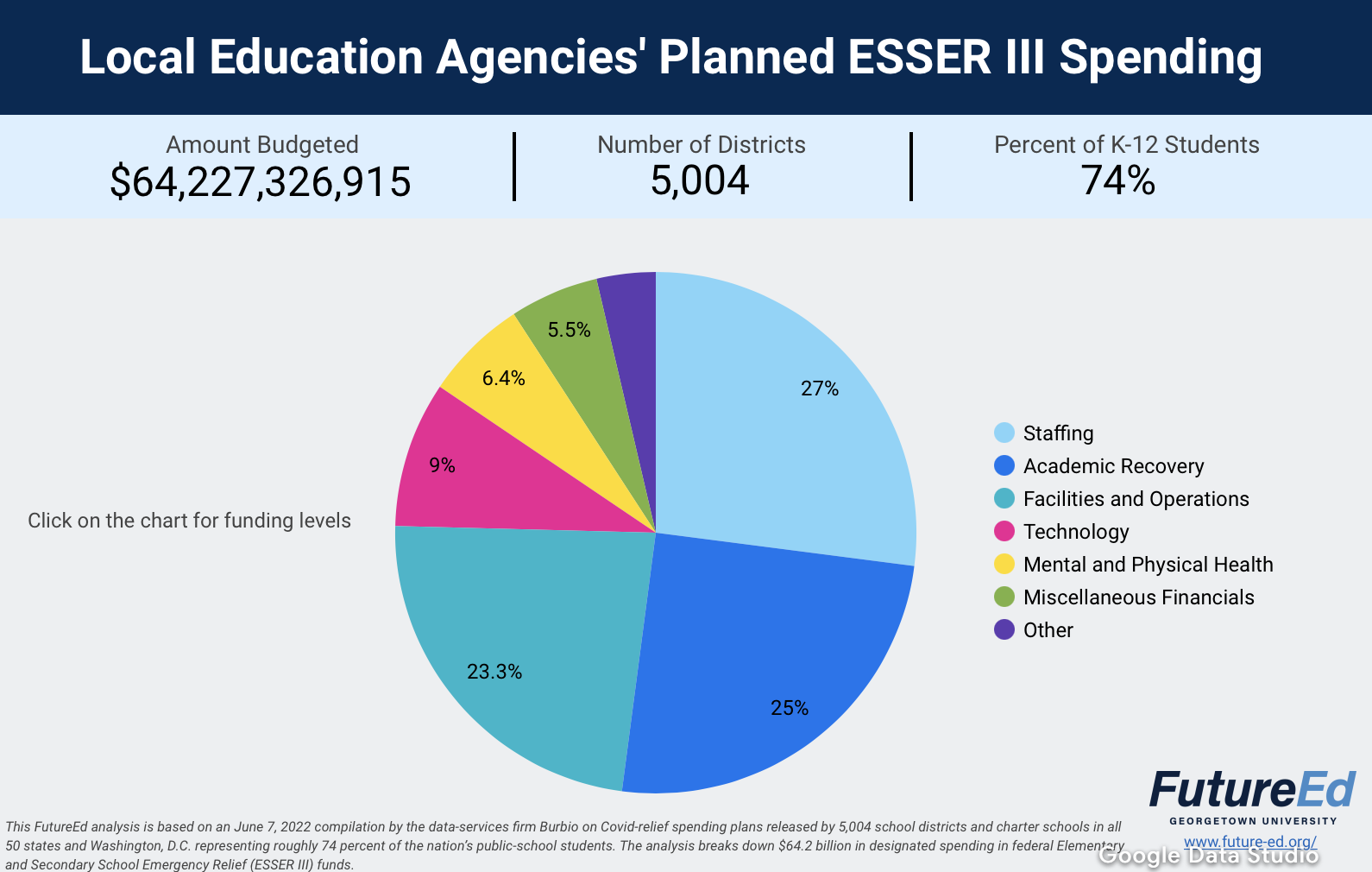

Before districts received any of the American Rescue Plan ESSER money, they were required to submit spending plans to their state education agency. These spending plans provide a window into the priorities that local educators are assigning to this $122 billion program. FutureEd analyzed a national sample of 5,004 local spending plans from districts and charter organizations serving 74 percent of the nation’s public school students. The data base, compiled by the Burbio data services firm, breaks down planned spending into about 100 categories, allowing us to see not only what districts and charters plan to spend on, but how much they plan to spend. FutureEd also examined the planned spending based on student poverty levels, geographic setting and state partisan lean. While these plans can and likely will change somewhat, the size of the sample yields valuable insights into how districts are prioritizing needs and how communities can hold local leaders accountable for spending the federal money effectively.

While new athletic facilities made headlines, our analysis shows that such expenditures make up very little of the money that districts have designated. Instead, local education agencies intend to use the bulk of their Covid-relief funds in ways that can not only improve student outcomes but also address longstanding needs.

If the trends continue through the September 2024 deadline for committing ESSER III funds, we expect to see:

• More than $27 billion on academic interventions, especially summer learning, afterschool programs and tutoring

• More than $30 billion on teachers and staffing, much of which goes to learning loss priorities such as hiring academic coaching or reducing class sizes

• Nearly $26 billion on school facilities and operations, particularly ventilations upgrades.

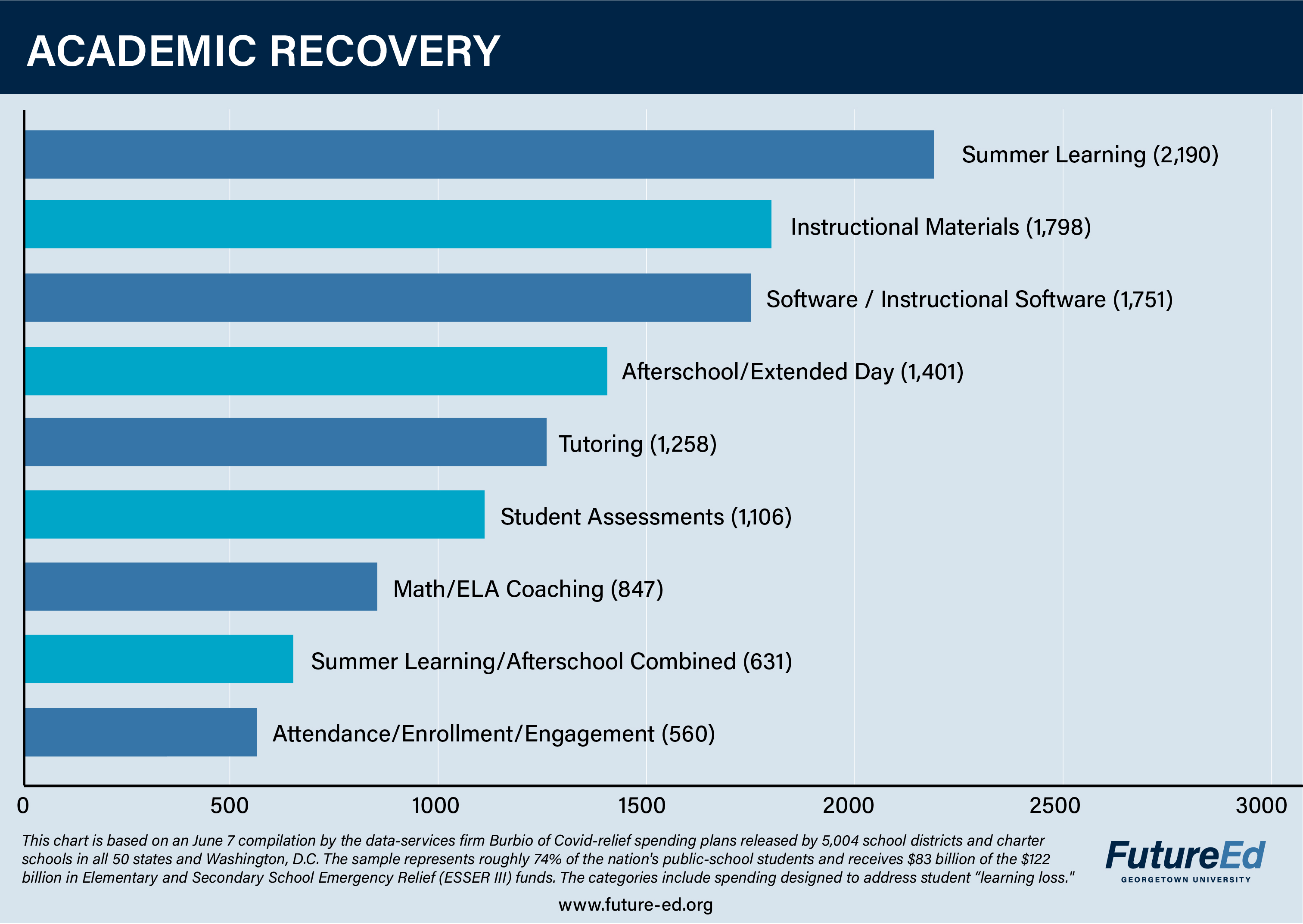

With the American Rescue Plan’s requirement that schools spend at least 20 percent of the federal aid to address learning loss, we’re seeing considerable investment in academic recovery strategies:

• Summer learning and afterschool programs make up nearly a quarter of the academic recovery spending, with about $3.7 billion earmarked for those categories. That number could be expected to grow to $6.3 billion nationwide.

• Tutoring and coaching for math and English language skills comprise another 12 percent, or $1.8 billion, which could eventually reach $3 billion if trends hold true. Many districts also set aside additional money for staffing these programs.

District Priorities for Academic Recovery

Beyond funding levels, we also looked at the numbers of districts designating funds for the evidence-based, academic recovery interventions. About 60 percent of the school districts and charter organizations in the sample plan investments in summer learning, afterschool programs or both. More than 300 plan to extend the school year or add weekend classes. In addition to our analysis of the national sample, FutureEd did a detailed review of plans for the 100 largest local education agencies, including one large charter organization, to see how the spending broke down. We found most districts put money toward summer learning, though the investments varied in length and strength. Some districts offered little more than the traditional summer school, with opportunities to take an extra class or make up for a course failure. But others had robust programs that combined recreation, arts and learning to help students recover academically. Many had a social aspect aimed at helping student re-connect and re-engage with school.

About a third of the districts nationally are earmarking funds either for tutoring or academic coaching. The percentage rose to two thirds when we reviewed plans for the 100 largest school districts. We saw a big emphasis on tutoring in early reading for the youngest students and in math for secondary school students. Districts are drawing on tutors from a range of sources, tapping existing staff, college students, volunteers, and community organizations. Several districts are using national service workers provided through AmeriCorps.

The district-level plans for academic recovery comes on top of the ESSER funds that states are spending to address learning loss. The American Rescue Plan requires states collectively to reserve $1.2 billion of their ESSER allotment for summer learning and $1.2 billion for afterschool programs, as well as $6 billion overall for addressing learning loss. In many states, this is taking the form of grants to local school districts and charters, as well as community-based organizations, such as Boys & Girls Clubs and the YMCA. At least 37 states earmarked money for tutoring efforts. Some states, Tennessee and Arkansas among them, are using their ESSER money to launch tutoring corps.

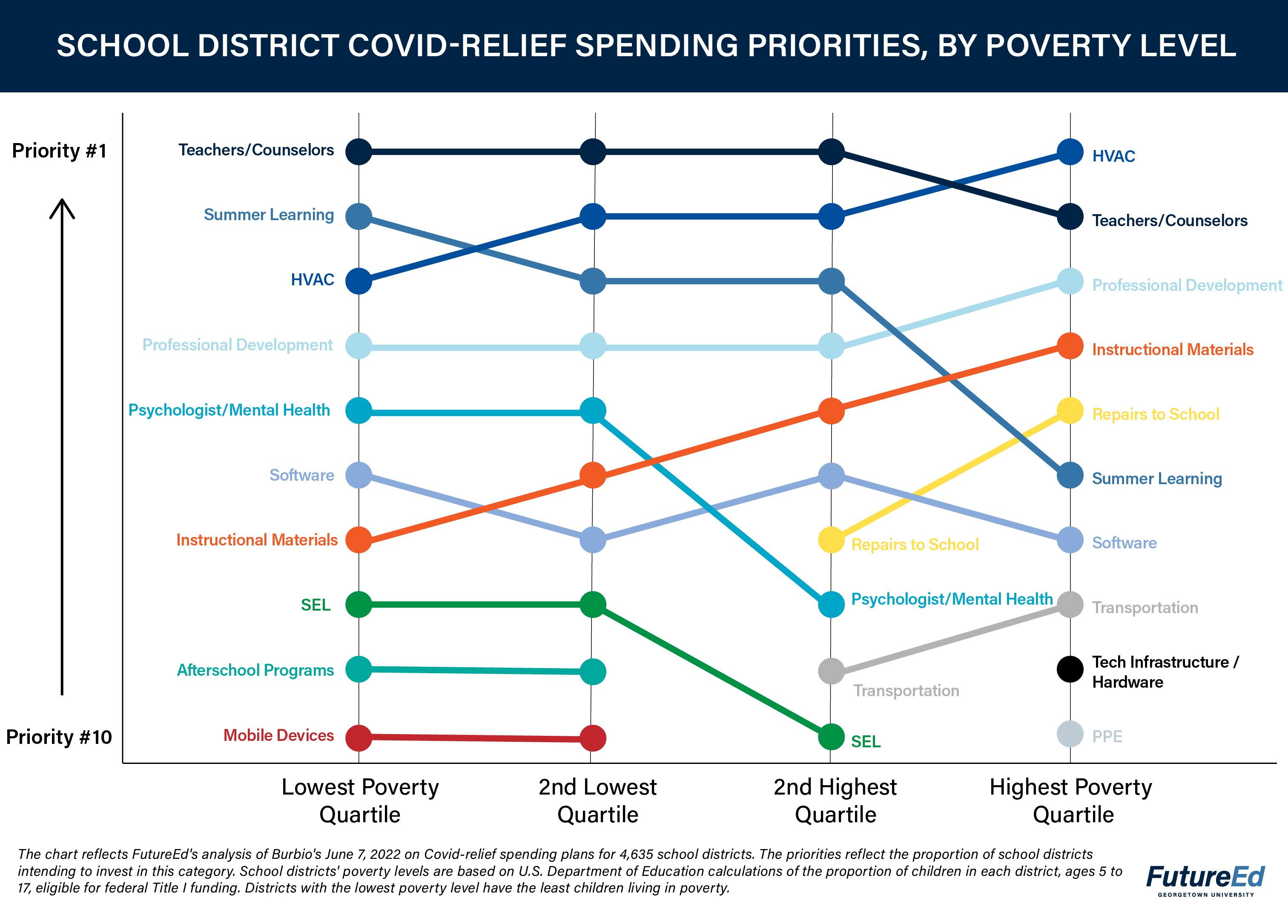

How Poverty Levels Influence Academic Spending

When we broke down the academic recovery spending based on the district’s poverty rate we found some distinct differences. We used U.S. Department of Education figures showing the proportion of children in each district, ages 5 to 17, eligible for Title I funding. We found that the higher the poverty rate, the more likely a district is to use ESSER aid for new instructional materials. We believe that some of these traditionally under-resourced districts are using the money to address some longstanding needs.

When we broke down the academic recovery spending based on the district’s poverty rate we found some distinct differences. We used U.S. Department of Education figures showing the proportion of children in each district, ages 5 to 17, eligible for Title I funding. We found that the higher the poverty rate, the more likely a district is to use ESSER aid for new instructional materials. We believe that some of these traditionally under-resourced districts are using the money to address some longstanding needs.

Afterschool and summer learning programs top the list of what more affluent districts are planning to spend on academic recovery, our analysis shows. To be clear, the districts with more children in poverty are also spending on extended learning time, but they’re putting a greater share of their funds toward instructional materials.

How Location Influence Academic Recovery Spending

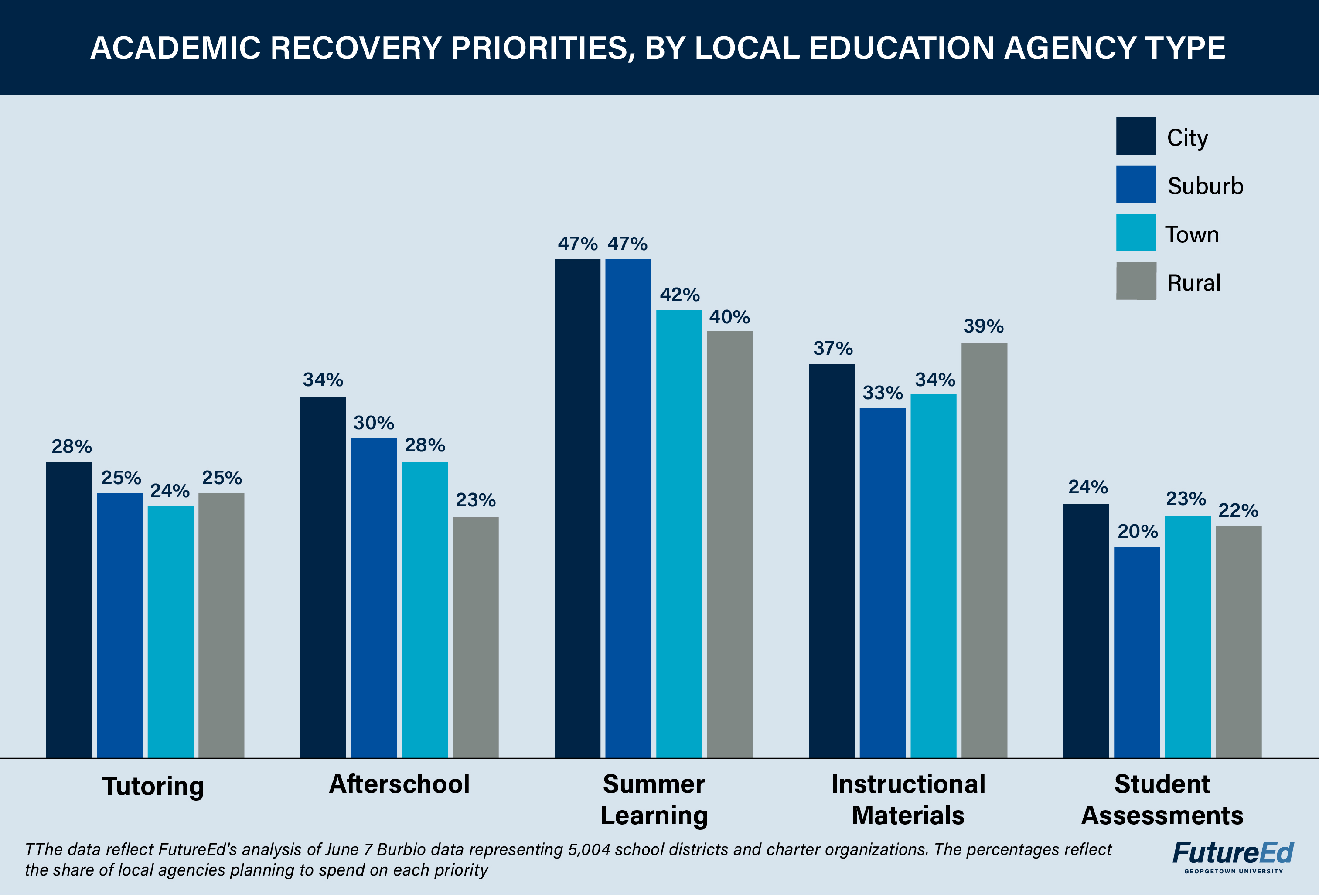

FutureEd also examined Covid-relief spending patterns using the National Center for Education Statistics’ four classifications of school district settings—city, suburban, towns, and rural.

FutureEd also examined Covid-relief spending patterns using the National Center for Education Statistics’ four classifications of school district settings—city, suburban, towns, and rural.

We found that rural districts were less likely to spend on extended time solutions, like afterschool, summer learning, and tutoring. About 34 percent of city districts and charters are planning to spend on afterschool programs, compared to 30 percent in suburbs, 28 percent in towns and 23 percent rural communities. A slightly higher share of city education agencies, 28 percent are planning to spend on tutoring, compared to 24 percent in suburban and rural communities and 24 percent in towns.

The transportation challenges rural districts face may shape their strategies—it’s harder to keep student for afterschool and summer programs when bus routes run across wide swaths of rural areas. The rural school districts in the sample were more likely than their urban counterparts to spend on instructional materials and assessments—which ranges from standardized testing to classroom progress checks.

How Partisan Lean Influences Academic Recovery Spending

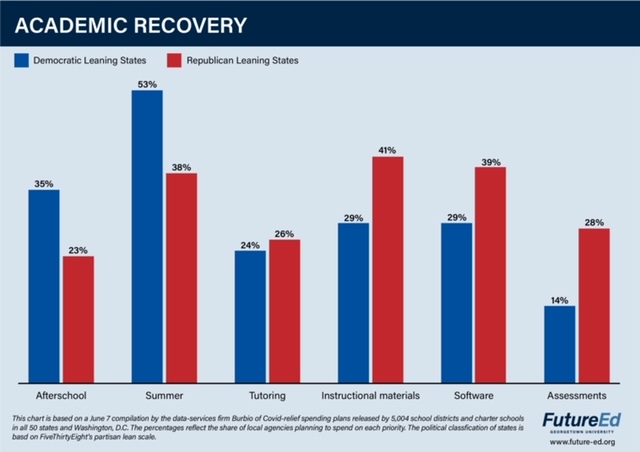

We broke down states by partisan lean using FiveThirtyEight’s ranking of how states voted relative to the rest of the country in a mix of recent elections. We found some notable similarities: nearly the same percentage of local education agencies in red and blue states earmarked ESSER III funds for social-emotional learning. Both have made hiring and rewarding teachers their top priority and plan to spend at similar rates on tutoring, teacher training and new school infrastructure. Red states are actually more likely than blue states to earmark funds for teacher bonuses and student assessments—counterintuitive findings given many conservatives’ opposition to testing in recent years and their fraught relationship with the teaching profession.

We broke down states by partisan lean using FiveThirtyEight’s ranking of how states voted relative to the rest of the country in a mix of recent elections. We found some notable similarities: nearly the same percentage of local education agencies in red and blue states earmarked ESSER III funds for social-emotional learning. Both have made hiring and rewarding teachers their top priority and plan to spend at similar rates on tutoring, teacher training and new school infrastructure. Red states are actually more likely than blue states to earmark funds for teacher bonuses and student assessments—counterintuitive findings given many conservatives’ opposition to testing in recent years and their fraught relationship with the teaching profession.

More than half of districts in blue states intend to spend on summer learning programs, making it their top learning-loss strategy and their No. 3 priority overall. By contrast, 38 percent of districts in red states plan to spend on summer learning, and it ranks No. 6 on their list of priorities. Spending on afterschool programs is also more common in blue states than their more conservative counterparts. Roughly 40 percent of districts in red states plan to purchase instructional materials, software and curriculum. This compares to about 30 percent of blue-state districts.

Staffing Priorities for Academic Recovery

Our analysis found that school districts and charter organizations plan to invest heavily in hiring and rewarding teachers and other staff who can support academic recovery. Nearly $30 billion or 27 percent of the spending in the national representative will go toward staffing, with a third of that going for teachers and academic staff. Districts are also spending on recruitment and retention efforts to ensure they have enough teachers to support student needs and on professional development for new curriculum and instructional techniques.

Overall, 60 percent of the school districts and charter organizations in the nationally representative sample are planning to spend Covid-relief funds on hiring and rewarding teachers, academic specialists and guidance counselors, making it the most popular choice across the different geographic settings and most poverty levels. Our review of the 100 largest districts provides some nuance to this picture, which we will share in a forthcoming report. We found that at least 63 districts earmarked money for hiring: about half bringing in teachers and half academic specialists, typically elementary school reading or math coaches. Some districts are hiring teachers to reduce class sizes, sometimes on a short-term basis for social distancing as well as to improve student learning. This comes despite the fact that ESSER spending will expire in 2024, leaving districts without the money to pay extra staff. Some district plans specify that the new hires will be temporary positions, but others are less clear.

At least 29 of the largest districts promised retention bonuses to teachers and staff, and in at least 13 places those bonuses are targeting hard-to-fill specialties, like special education and high school science and math, or hard-to-fill schools. A few places are providing bonuses to effective teachers. Bonuses are a more sustainable spending approach than permanent salary hikes that will be hard to continue when the federal aid is spent. But the across-the board bonuses that many districts have embraced are not as effective as the more targeted approaches.

Investing in Mental and Physical Health

Beyond academics, many districts are helping students recover from the isolation and trauma of the pandemic, a priority that President Biden stressed in his State of the Union address and a subsequent initiative to address youth mental health. Mental and physical health spending—on such priorities as social-emotional learning, testing and vaccines—add up to about $4 billion of the spending designated so far, a figure projected to rise to $7 billion if trends continue. About a third of local education agencies in the database list social-emotional learning in their spending plans. That includes, funding for curricula, classroom materials, and training. On top of that more than a third of the sample are planning to bring psychologists or mental-health professionals into schools to work with students, adding another $1.3 billion to the designated spending and $2.2 billion to projections.

Our breakdown of districts by poverty level found the more affluent districts are more likely to spend Covid-relief money on mental-health services than their higher-poverty counterparts. About 40 percent of the most affluent quartile of districts are earmarking money to provide psychologists and other mental health professionals to help students and staff deal with pandemic-related trauma, compared to 32 percent of the highest poverty quartile. When we looked across geographic settings, we found city and suburban communities more likely to designate Covid-relief dollars for mental health professionals and social-emotional learning programs than their counterparts in rural areas and towns.

Spending on Facilities and Operations

Nearly a quarter of the spending designated would pay for facilities and operations priorities, particularly upgrades to heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems—a use explicitly allowed under the American Rescue Plan. More than $5.7 billion is earmarked for these projects, which could reach $9.7 billion by the time the ESSER III money is spent. Another $2.8 billion is set aside for “repairs that prevent illness,” a priority that includes lead abatement, removing mold and mildew, improving bathrooms, or replacing leaking roofs, which is projected to reach $5 billion.

More than half the districts in our analysis expect to spend money on HVAC, which is a top-three priority in every region of the country. The plans range from thousand-dollar investments in filters that block the spread of the virus to multi-million-dollar plans for replacing entire HVAC systems. The higher the poverty rate in a district’s student population, the more likely its administrators are to devote the federal aid toward renovating aging ventilation systems and other repairs to schools, our analysis showed. As with instructional materials, this may reflect the pent-up need for repairs to aging systems.

In addition to mitigating the spread of Covid, better ventilation can contribute to better student outcomes. We saw how schools in Philadelphia and Baltimore shut down at the start of this school year because air conditioning systems weren’t working. Research shows that learning suffers when students are too hot or too cold in the classroom. Mold and mildew contribute to absenteeism, especially for students with asthma—the No. 1 cause of student absences before the pandemic. Exposure to lead, through contaminated water or peeling paint, can contribute to learning delays and behavioral problems. Fixing these problems can ultimately create safer, healthier learning environments.

Status of Spending

Our analysis of spending plans shows us that local educators have a clear sense of how they expect to use the federal aid through the September 2024 deadline for obligating the funds. Given the learning loss that many students have experienced, policymakers and educators naturally feel some urgency to spend money for academic recovery as quickly as possible. The latest data from the U.S. Education Department portal shows that across the three rounds of ESSER funds, $56 billion or about 30 percent has been used as of late July. For ESSER III, about $17.1 billion or about 14 percent has been spent.

In considering these trends, it’s important to keep a few things in mind. First reporting lags behind actual spending, as do district requests for reimbursement. Plus, the spending totals don’t reflect what’s committed for the years ahead. Delays in state allocations and the requirements of federal procurement rules can also slow down the spending process.

What’s more, some districts that have access to the money can’t find the people they want to hire. The pandemic has exacerbated longstanding shortages in critical teaching areas, particularly special education, science and math. And with many districts hiring more teachers and specialists, there are more positions to fill. One superintendent told us how larger districts were poaching some of his strongest teachers. While we haven’t seen the exodus of teachers that many pundits predicted, many districts are struggling to fill their vacancies. Districts are also having problems finding tutors and staffing summer and afterschool programs—slowing down their ability to spend money on these priorities.

Promising Practices

After two years of ESSER spending, we have begun to see some promising policies and practices from states and school districts that could warrant future funding.

They include:

The science of reading: The evidence-based notion that children learn to read better when they’re taught the sounds that letters and syllables make has gained traction again in recent years. The infusion of Covid-relief dollars has supercharged efforts to train teachers and buy the materials needed for this phonics-based approach. Richmond, Virginia, for instance, is putting more than half of its $122 million ESSER III allotment toward a literacy push, which includes training teachers on powerful curriculum known as LETRS or Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling. North Carolina is putting $12 million of the state’s ESSER share toward LETRS training. This training—and its impact on students—will last long after the relief money is gone.

Targeted bonuses: After decades of paying every teacher on a single scale, post-pandemic shortages and the availability of federal funding have led increasing numbers of districts to target extra pay for hard-to-fill slots. Houston, for instance, is using its ESSER money to offer added bonuses for teachers qualified for special education, English language classes and upper level math and science. The school district is also offering $15,000 bonuses to teachers who will lead a team of instructors, providing a level of teacher collaboration and coaching that is crucial to promoting good learning. Detroit is offering $15,000 recurring bonuses for special education teachers. These steps are more effective in addressing shortages while maintaining the quality of instruction than small across-the-board bonuses for all staff members or lowering entry standards to the teaching profession by, for example, eliminating requires that applicants have college degrees.

Intensive tutoring: The need to catch students up academically post-pandemic has led to a resurgence of tutoring, one that has come with a heightened awareness of evidence-based tutoring practices. A good example is Tennessee, where officials used the state’s share of earlier rounds of federal Covid-relief funding and other resources to earmark an estimate $200 million for the Tennessee Accelerating Literacy and Learning (TN ALL) Corps. The state initiative, established by the Tennessee legislature, recruits tutors, develops content for lessons, and provides matching grants to local education agencies. The state set evidence-based standards for the program, including requiring that students receive at least two sessions a week for 30 to 45 minutes each, with no more than three students in elementary school and four in middle school working with a tutor at one time. At least 82 percent of Tennessee’s school districts signed on for the initiative, and an analysis by Tennessee SCORE suggests that about half the districts they reviewed are using evidence-based practices.

Attention to student mental health: Educators have said for years that students need more support managing the mental health problems they bring to school. The ESSER funding is delivering billions of dollars in support. We see places like the Poway Unified School District in the San Diego area, which is earmarking nearly $10 million of its $17 million ESSER III allotment for hiring social workers, psychologists and counselors in its 38 schools. The Hot Springs School District in Arkansas, which is spending $1.2 million of its $21 million allotment to employ therapists in some of its six schools.

This comes on top of money spent for social-emotional learning and school climate initiatives. The next two years should show us the impact of increased mental health support. If that impact is strong, we suggest that the federal government provide more funding for these programs and that the government simplify the Medicaid reimbursement process to make it easy to recover money spent on eligible students.

Making the case for these initiatives requires evidence that they are working. Some states, particularly Connecticut and North Carolina, are spending some of their state ESSER allotment to assess interventions that districts are using. They’re tapping the expertise of researchers within their states, and asking for a quick turn around on the findings, so they can use the results to adjust their approach, increase spending or shift priorities. The U.S. Department of Education is also conducting research, as well as sharing existing evidence on effective practices. Ultimately, the goal is to emerge from the pandemic with stronger evidence of what works to improve learning outcomes, especially for our most underserved students.