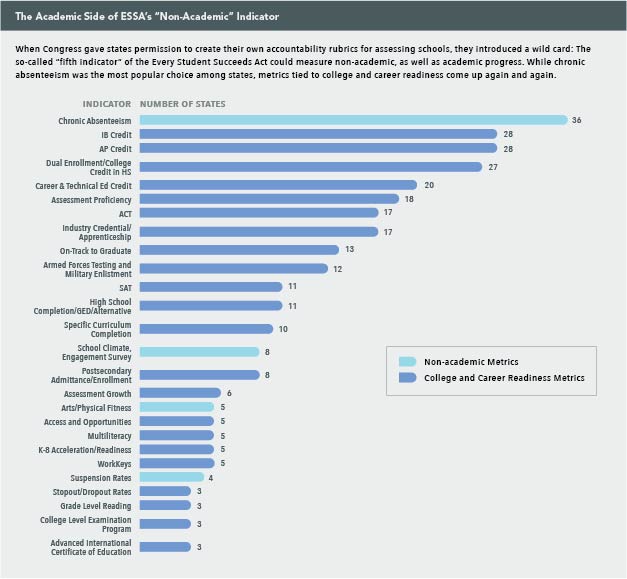

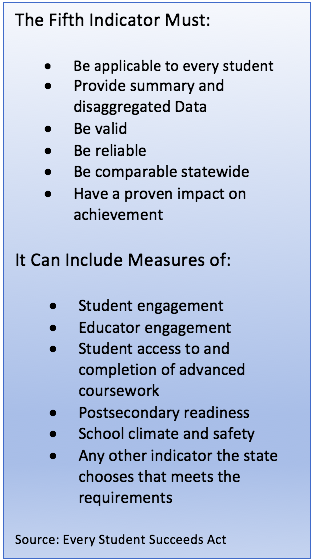

When Congress rewrote the federal No Child Left Behind Act to give states greater flexibility in measuring school performance, lawmakers inserted a wild card. They required traditional academic metrics, including proficiency on standardized assessments, test score growth or another academic measure, graduation rates and progress for English language learners.

But in an effort to dilute the influence of standardized tests in the nation’s classrooms, a move pressed by teacher unions, the law also requires states to include at least one measure of “school quality and student success” that went beyond academic outcomes.

The law encouraged states to include metrics such as “postsecondary readiness,” and “completion of  advanced coursework,” but it also suggested “school climate” and “student engagement.” Many education experts and school reformers hoped that states would embrace non-academic contributors to student success such as student self-management and social awareness—so-called social emotional skills that create classroom conditions conducive to learning.

advanced coursework,” but it also suggested “school climate” and “student engagement.” Many education experts and school reformers hoped that states would embrace non-academic contributors to student success such as student self-management and social awareness—so-called social emotional skills that create classroom conditions conducive to learning.

In the end, three fourths of the states chose to include chronic absenteeism in their fifth indicators, providing a window into student engagement and other aspects of school culture that along with social emotional learning contribute to student success.

But many of them simultaneously adopted a distinctly academic measure of school performance in their fifth indicators: college and career readiness. And often the readiness metrics are given much more weight than chronic absenteeism, a new FutureEd analysis shows.

Adding chronic absenteeism to an accountability rubric makes a lot of sense. As recent headlines from the District of Columbia make clear, the problem is severe. Data is readily available and relatively straightforward to interpret. And the metric can reveal not just disengaged students headed off track but also problems with a school’s climate. Four states plan to hold schools accountable for student suspension rates, which also reflect school climate and safety.

A handful of states have sought to capture student engagement more directly—requiring schools to administer annual surveys to students on non-academic topics ranging from safety to the quality of teaching and learning, and the strength of relationships between adults and students.

Done right, such surveys can illuminate students’ sense of themselves as learners and as members of school communities—key factors, a growing body of research suggests, in students’ willingness to work hard in school, to persevere in the face of academic and social challenges.

Only the District of Columbia plans to explicitly measure an aspect of social emotional learning (SEL)—described as “social-emotional support and community/family engagement” in early learning settings. Kentucky intends to award points to schools where students have access to mental health counselors under an “Educating the Whole Child” initiative. Colorado discusses the possibility of creating an SEL fifth indicator in the future, without specifying what form that would take.

But the inclusion in two thirds of the states of career and college readiness in their fifth indicators could dilute school districts’ focus on non-academic contributors to student success, especially since many states have given these academic proxies substantially more weight in their ESSA formulas than chronic absenteeism and student surveys.

States define career and college readiness variously as the availability of advanced high school coursework and apprenticeships, qualification for military service, and a strong performance on college admissions tests, the career and college readiness measures.

Research by Paige Marley. Design by Jackie Arthur Designography

Our analysis of state ESSA plans finds that several states—Alaska, D.C., Georgia, Nevada, Ohio, and Tennessee—assign double or even triple the weight to college and career readiness that they give to chronic absenteeism in their fifth indicator formulas. States such as Arizona, Indiana, and South Dakota measure chronic absenteeism in grades K-8 then drop it for high schools, where they prioritize career and college readiness. Only five states—Alabama, California, Montana, Oklahoma, and Oregon—weight absenteeism and career and college readiness equally in high school.

Given that the first four indicators in every state’s ESSA plan are academic metrics, the lower weighting for chronic absenteeism in the fifth indicator means the law isn’t likely to be the dramatic catalyst for attention to the non-academic side of student success that some advocates had hoped it would be.

That puts pressure on advocates to make clear to policymakers and practitioners the relationship of chronic absenteeism to important upstream contributors to student success, including school culture, students’ sense of themselves as learners, and teachable social and emotional competencies. It points to the importance of measuring chronic absenteeism accurately and in ways that incentivize educators to address the problem rather than try to conceal it.

[Read More: Who’s In: Chronic Absenteeism Under the Every Student Succeeds Act]

It requires the policy community to supply practitioners with concrete, cost-effective strategies for reducing chronic absenteeism, enhancing students’ social emotional skills, and strengthening school cultures in ways that build students’ confidence in themselves as learners and their sense of connectedness to the schools they attend. And it requires increased attention to the challenging task of accurately measuring schools’ success in achieving these aims.

With its commitment to widening the aperture of school improvement to include non-academic contributors to student success, ESSA has presented an opportunity to expand a potentially powerful new strategy for raising student achievement.

But given what on close inspection is a modest role for the new school measures under the state’s initial ESSA plans, policymakers and practitioners could easily focus their energies only on the academic side of the school equation in the months and years ahead. An important opportunity could be lost if substantial steps aren’t taken to build a policy and political infrastructure to scale non-academic strategies for student success.