When students started dropping off the school rolls during the pandemic, Connecticut put $10.7 million of its federal relief aid toward a home visiting program designed to connect with families and bring students back to school.

A study released in January shows that the Learner Engagement and Attendance Program (LEAP) made a significant difference in reducing student absenteeism, particularly with secondary school students.

The new research is important for two reasons. First, it showcases a powerful intervention for improving student attendance, which is essential for academic recovery. Second, it highlights a second Connecticut initiative: using federal aid to create a research consortium that can turn around results quickly and guide district-level work.

“We have made it a priority to remain transparent about the effectiveness of federal and state recovery funding used to create programs such as LEAP,” Connecticut Education Commissioner Charlene Russell-Tucker said in a news release announcing the results.

Fifteen school districts received money for Connecticut’s LEAP program, which they used to pay school staff and community organizers to visit nearly 8,700 chronically absent students and families at their homes or other locations. One district targeted entire neighborhoods rather concentrating on students with the most severe absenteeism problems and saw little change in attendance patterns.

For most of the students, though, attendance rates increased by four percentage points in the month immediately following the first visit and climbed 15 percentage points after six months, often after multiple visits, researchers found. The biggest gains came in Hartford Public Schools, which saw attendance rates improve by 30 percentage points in that six-month timeframe. The chronically absent students had missed at least 10 percent of the school year, meaning their initial attendance rate was no higher than 90 percent. For some it fell far lower. So a 15-point gain could take a student from missing a day a week to missing a day every month.

Some districts used school staff to make the visits, while others tapped community organizations. Attendance rates increased regardless of who made the visit, the study showed. What did make a difference was how they connected. While some visitors used phone calls or Zoom to reach families, these approaches were not as effective as the in-person visits, the researchers found.

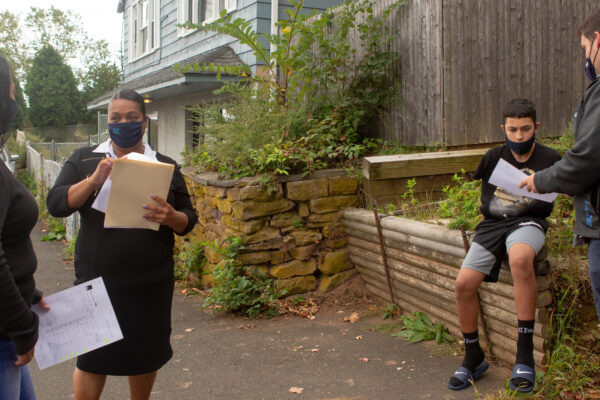

We wrote about the LEAP program in a story for The New York Times last fall, focusing on Torrington, a 4,000-student district in northwestern Connecticut that saw its chronic absenteeism drop by nearly a third after initiating the visits.

About 65 Torrington teachers and other staffers visited 350 families whose children had become chronically absent. The home visitors focused on middle and high school students, many of whom had been in remote learning longer. We talked with Claudia Ocasio, a family engagement liaison with the district, who conducted many of the visits. She found that the biggest reason students were missing school amid the height of the pandemic was because families were scared to send them.

We also talked with researchers from Connecticut higher education institutions who evaluated the program’s effect on attendance and other results. The state used its share of federal Covid-relief dollars to launch the Center for Connecticut Education Research Collaboration, pulling together eight higher education institutions to assess the impact of recovery efforts.

A team of researchers led by Steven Stemler, a psychology professor from Wesleyan University, began evaluating the LEAP project in spring 2022. The team tracked the number of visits with students and families, the type of visits, and the impact on attendance compared to similar students who weren’t in the program. The team also interviewed families and home visitors to see what worked best.

The report not only provides results but points to practices that made the effort more effective, including paying home visitors, taking steps to ensure their safety, connecting families to visitors who speak their home language, and repeating visits to build stronger connections with families.

Rather than the years-long lag time that often accompanies education research, the team was able to turn the results around in a matter of months, allowing Connecticut districts to adapt their approaches going forward. This sort of fast turnaround is also key to North Carolina’s efforts to use federal Covid aid for seeding research that track how various interventions are working.