Among the Covid-19 pandemic’s most pernicious aftershocks is its impact on student mental health. Isolated at home, disconnected from friends, and suffering trauma from family members’ job losses or Covid-related deaths, students are experiencing high levels of anxiety and depression.

About 44 percent of adolescents experienced persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness during the pandemic compared to 37 percent in 2019, according to a recent survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In schools, students’ struggles manifest themselves as misbehavior, disengagement from school work, and spiraling absenteeism.

Recognizing this, school districts across the country are using federal Covid-relief aid to bring mental health professionals into school buildings and to expand social-emotional learning programs. Public schools have received nearly $190 billion in three waves of federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief, or ESSER, that can be used for a range of priorities, including school-based mental health supports.

But the unprecedented infusion of federal aid also creates a challenge: how to sustain new school staff positions when the funding expires at the end of 2024. Medicaid, the federal-state partnership that provides health care for millions of public-school students, could be part of the solution—as long as states take the necessary steps to use the tool and federal agencies back them up.

Unprecedented Resources

In the latest round of ESSER funding—$122 billion allotted in the 2021 American Rescue Plan—school districts and charter school organizations were required to submit plans detailing how they expect to spend the federal dollars. Drawing on a database of more than 4,400 local spending plans compiled by the data-services firm Burbio and covering 70 percent of the nation’s students, FutureEd found that more than a third of the local education agencies have earmarked a total of $1.2 billion in ESSER funding for psychologists, social workers and mental health counselors. If the trend continues, the investment could reach more than $2 billion.

The local jurisdictions range from the Poway Unified School District in the San Diego area, which is earmarking nearly $10 million of its $17 million ESSER III allotment for hiring social workers, psychologists and counselors in its 38 schools to the Hot Springs School District in Arkansas, which is spending $1.2 million of its $21 million allotment to employ therapists in some of its six schools.

School districts in nearly all states are making these investments, but the strategy is more popular in some states than others: 263 of the 583 California districts in the Burbio sample are planning to spend ESSER III funds on mental health professionals, compared to five of the 215 Arkansas districts in the sample.

[Read More: How Local Educators Plans to Spend Billions in Federal Covid Aid]

And local investments vary by geographic setting: 43 percent of districts and charters in cities and 41 percent of those in suburbs plan to spend on mental health workers, compared to 34 percent in small towns and 27 percent of rural districts, the analysis of the sample shows. This may reflect, in part, a lack of available counselors and psychologists in more remote communities. Even in urban settings, some schools report having difficulty finding the mental health workers they need to support students.

Investments also vary by community poverty rates. Dividing the school districts in the Burbio database into four quartiles, FutureEd found that 32 percent of the districts with the highest poverty levels plan to bring in mental health professionals, compared to 40 percent of the most affluent quartile. The analysis did not include charter schools, for which poverty information was not readily available. Taken together, these are distressing findings, given the critical need for mental health supports among students in rural communities and in low-income neighborhoods.

Still, the White House estimates that public schools have already seen a 65 percent increase in the number of social workers and 17 percent increase in counselors in recent months, due in large part to the latest round of ESSER funding. Sustaining funding will be a challenge. That’s where Medicaid could be a critical tool.

Leveraging Medicaid

States and school districts can leverage Medicaid to support mental health care for students through a variety of mechanisms, including through school-based health centers and partnering with community providers. Georgia’s Apex program is an example. For school districts that have hired their own mental health professionals and plan to keep those positions after ESSER funds expire, school Medicaid programs could help fill the funding gap.

In 2014, the federal government opened up a new avenue for support when it reversed what’s known as the “free care rule” and allowed schools to seek Medicaid reimbursement for some health services provided by school employees, including mental health counselors, for all students enrolled in Medicaid. Previous guidance limited reimbursement to services included in a student’s Individualized Education Plan (IEP) or Individualized Family Service Plan under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

In 2019, about 36 percent of school-aged children were enrolled in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), according to estimates by Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families. That number is likely even higher today, given that about half of all children in the United States (40 million) were enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP as of January 2022, the vast majority through Medicaid. Given this, allowing school districts to receive reimbursement for services delivered by mental health workers and other health providers on their payroll could go a long way to sustain school mental health services after ESSER funds expire.

But at this point, not every district has that option. Expanding reimbursement beyond Medicaid-enrolled students with IEPs requires state action, often through submitting a Medicaid State Plan Amendment for approval by the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. In some cases, the state legislature must first sign off on the change.

Expanding School Medicaid Programs

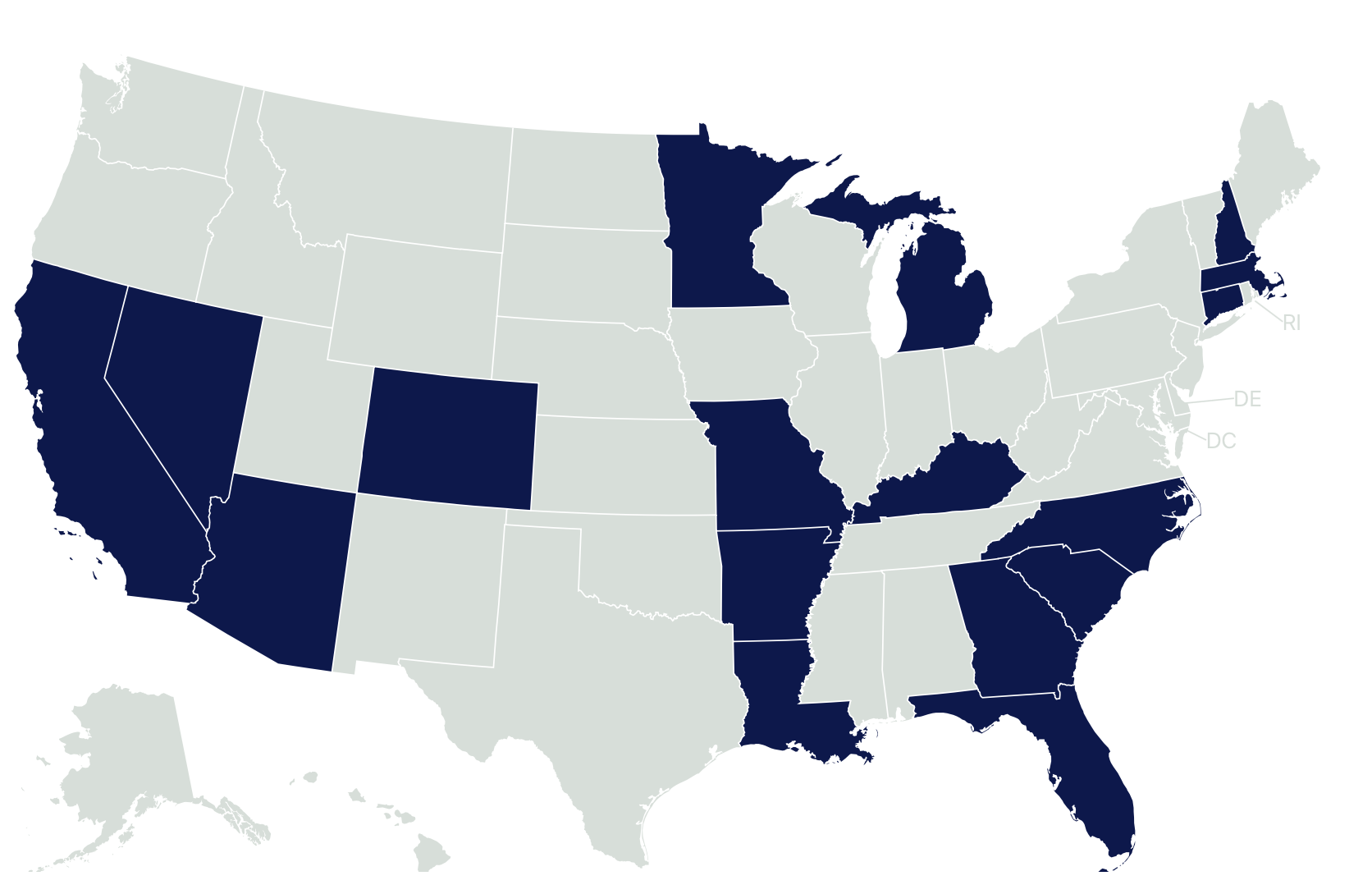

Currently, 16 states—Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts,  Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, North Carolina, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina—have expanded their programs to allow qualified school providers to bill for covered behavioral health services for Medicaid-enrolled students beyond those with IEPs, according the Healthy Schools Campaign.

Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, North Carolina, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina—have expanded their programs to allow qualified school providers to bill for covered behavioral health services for Medicaid-enrolled students beyond those with IEPs, according the Healthy Schools Campaign.

Connecticut limits the expansion to students with 504 plans, which are provided for some students with disabilities who don’t have IEPs. Georgia has also expanded its school Medicaid program but limits reimbursement to nursing services and thus was not included in this group for purposes of this analysis. Another five states—Illinois, Indiana, New Mexico, Oregon and Virginia—are in the process of expanding their programs but have not yet implemented them.

FutureEd’s analysis found that just over half of the 1,566 school districts and charter organizations in the Burbio sample that devoted federal ESSER funds to mental health professionals were in the 16 states that have expanded their school Medicaid programs or in the states in the process of expanding. That means the other half that are investing ESSER III aid in mental health professionals are in states that do not allow broader reimbursement—and thus have limited options in using Medicaid to help sustain mental health staff on school payrolls once the federal Covid-relief aid expires in late 2024.

The Biden Administration’s Commitment

The federal government could help address the problem. A White House fact sheet released alongside President Joe Biden’s 2022 State of the Union address suggests the administration agrees. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is working to “make it easier for school-based mental health professionals to seek reimbursement from Medicaid,” the document says. President Biden announced in early March that he has asked the U.S. Education Department to work with HHS in developing guidance that can help schools offer more mental health support. “And this is going to include enabling schools to use Medicaid funds to deliver those important services,” the President said at a cabinet meeting. The Administration and its health and human services agency leaders could support this goal by:

Releasing updated resources and guidance on Medicaid and school-based health services to encourage states to expand access to mental and behavioral health care. This could include updating a 2003 Medicaid school-based guide for how to submit administrative claims and updated guidance.

Such guidance could highlight opportunities for states to expand their school Medicaid programs under the free care reversal and provide claiming and billing information on topics such as parental consent and the alignment of Medicaid and education licensure and provider requirements. Best practices for service delivery including the use of telehealth would also be helpful, as would strategies to address challenges to staffing school-based health services.

Offer learning collaboratives and additional technical assistance to states and school districts, especially for small and rural school districts with less capacity, to share successful strategies and opportunities such as improving Medicaid billing. This could also help districts, which face challenges in determining which providers are qualified for reimbursement and developing administrative tools and capacity for making claims.

[Read More: What Congressional Funding Means for K-12 Schools]

Beyond these efforts, President Biden’s fiscal year 2023 budget includes proposals to devote $1 billion for more school-based mental health professionals, including counselors, nurses, psychologists, and social workers. The budget also supports a number of broader mental health initiatives, including $700 million in proposed funding for programs that would provide training, scholarships and loan repayment for mental health providers willing to work in rural areas and other communities with limited access to services. And it includes more than $30 billion in Medicaid and mental health proposals, such as expanding access to certified community behavioral health clinics.

Congressional action would be required to move such proposals forward. Encouragingly, a number of Congressional committees have announced bipartisan legislative efforts on mental health including children’s mental health. Most recently, the House Energy & Commerce Committee included legislative language requiring HHS to issue guidance to state Medicaid agencies, elementary and secondary schools, and school-based health centers on reducing administrative barriers to providing health care services in schools as part of a May 11 committee markup.

Schools can serve as important partners in addressing students’ mental-health needs, especially if leaders remove barriers to school Medicaid programs. As the Surgeon General noted in his recent advisory on the youth mental health crisis, improving student mental health is ultimately going to require a “whole-of-society” effort. Hopefully, the pandemic has made clear to educators, health care providers, and society as a whole the importance of students’ mental and behavioral health to their academic success.

This report is a collaboration between FutureEd and the Center for Children and Families, both affiliated with Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy.

More Resources: