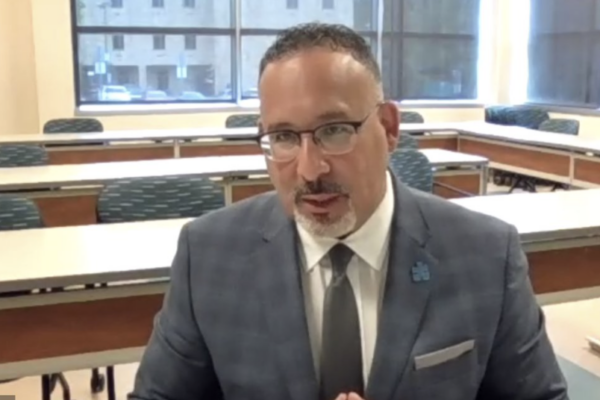

Connecticut Education Commissioner Miguel Cardona’s remarks accepting Joe Biden’s nomination to become U.S. secretary of education provides some insights into why the president-elect chose the grandson of Puerto Rican immigrants to be the nation’s top educator and glimpses of his priorities. FutureEd Director Thomas Toch annotated Cardona’s Dec. 23 speech.

Thank you for this opportunity to serve. I know how challenging this year has been for students, for educators, and for parents. I have lived those challenges alongside millions of American families, not only in my role as state education commissioner, but as a public school parent and as a former public school classroom teacher.

Toch: Cardona in stressing his public-school credentials is distancing himself and the Biden administration from the private sector-centric priorities and policies of the Trump administration. The Biden team has been under intense pressure from teacher unions, other elements of the public education establishment and their left-leaning allies in the Democratic party to promote a traditional, government-owned-and-operated vision of education delivery.

For so many of our schools, for far too many of our students, this unprecedented year has piled on crisis after crisis. It has taken some of our most painful, longstanding disparities and wrenched them open even wider. It has taxed our teachers, our leaders, our school professionals and staff who already pour so much of themselves into their work. It has taxed families struggling to adapt to new routines as they balance the stress, pain, and loss that this year has given. It has taxed young adults trying to chase their dreams to advance their education beyond high school and carve out their place in the economy of tomorrow.

Toch: Helping schools and colleges rebound from the pandemic is going to dominate Cardona’s agenda at the outset of his tenure at 400 Maryland Avenue, as it has as Connecticut education commissioner. The learning loss has been devastating in elementary and secondary schools, enrollment is down in higher education, especially among traditionally underserved students, and the financial foundations of many colleges and universities have crumbled.

And it has stolen time from our children. We have lost something sacred and irreplaceable this year despite the heroic efforts of so many of our nation’s educators. That we are beginning to see light at the end of the tunnel, we also know this crisis is ongoing, that we will carry its impact for years to come, and that the problems and inequities that have plagued our educational system since long before Covid will still be with us even after the virus has gone.

So it is our responsibility, it is our privilege to take this moment and to do the most American thing imaginable, to forge opportunity out of crisis, to draw on our resolve, our ingenuity, and our tireless optimism as a people, and build something better than we have ever had before.

Toch: For Cardona’s words to be more than empty rhetoric, he is going to have re-engage the nation on the difficult and unfinished work of school reform, improving the performance of the nation’s public schools and colleges, a task that includes teaching students to higher standards and one that will require much more than increasing education spending.

That is the choice Americans make every day. It is the choice that defines us as Americans. It is the choice my grandparents made…. when they made their way from Puerto Rico for new opportunities in Connecticut.

Toch: Cardona’s nomination helps fulfill Biden’s pledge to have a racially diverse cabinet, leadership that “looks like America.”

I am proud to say I was born at the Yale housing projects, that’s where my parents instilled early on the importance of hard work, service to community, and education. I was blessed to attend the public schools in my hometown in Meriden, Connecticut, where I was able to expand my horizons and become the first in my family to graduate college and become a teacher, a principal, and assistant superintendent in the same community that gave me so much.

Until his appointment as education commissioner in 2019, Cardona spent his entire career in Meriden, a working class, majority-Hispanic central Connecticut town where student test scores are below state averages.

That is the power of America. I, being bilingual and bicultural, am as American as apple pie—am as American as apple pie and rice and beans. For me, education was the great equalizer. For too many students your zip code and your skin color remain the best indicators of the opportunities you will have in your lifetime. We have allowed what the educational scholar Pedro Noguera calls the “normalization of failure” to hold back too many of America’s children.

Toch: Noguera is the dean of the University of Southern California Rossier School of Education and a darling of the education establishment. Cardona rightly highlights a pervasive problem in American education. Breaking the link between students’ backgrounds and their future prospects—ending the assumption that “demographics are destiny”—has been the central work of school reformers for several decades. President George W. Bush famously captured a key dimension of the problem in condemning a pervasive “soft bigotry of low expectations” for students of color and low-income students in the education sector. But centrist Democrats have pursued very different solutions to the problem than Noguera and others on the left. The question is whether Cardona can keep the two camps from attacking each other and move the cause of school reform forward. That Biden didn’t nominate a secretary with established connections to one side or the other suggests that the president-elect hopes Cardona can play a mediating role.

For too long we have allowed students to graduate from high school without any idea of how to meaningfully engage in the workforce, while good paying, high skilled, technical and trade jobs go unfilled. For far too long we have spent money on interventions and Band-aids to address disparities instead of laying a wide, strong foundation of quality, universal early childhood education and quality social and emotional supports for all of our learners.

Toch: The large-scale efforts in recent decades to raise standards and outcomes in public schools, strengthen the teaching profession, improve instructional materials, and incentivize innovation hardly amount to “Band-aids.” Expanding high-quality preschool opportunities, especially for low-income students, would be a valuable step, research suggests, though it is a very expensive proposition and it won’t be easy to produce high-quality programming at scale.

For far too long we have let college become inaccessible to too many Americans for reasons that have nothing to do with their aptitude or aspirations and everything to do with cost burdens and, unfortunately, an internalized culture of low expectations for some.

Toch: The soft bigotry of many educators’ low expectations has a devastating impact on students’ sense of their possibilities.

For far too long we have worked in silos, failing to share our breakthroughs and our successes in education. We need schools to be places of innovation, knowing this country was built on innovation.

Toch: A wide range of innovators have entered public education through charter schooling and through organizations such as Teach For America, the sorts of talented people who have eschewed public education in the past. The public education establishment has refused to acknowledge this reality, instead focusing on bad actors in the charter sector (which need to be addressed in a way that doesn’t undermine the charter sector as a whole).

For far too long, the teaching profession has been kicked around and not given the respect it deserves. It shouldn’t take a pandemic for us to realize how important teachers are for this country.

Toch: The nation’s teacher unions deserve substantial blame for the current standing of the public school teaching profession. Since their rise in the 1960s, unions have helped make teaching a low-status occupation marked by weak standards and factory-like work rules. And they have largely fought reforms that would transform teaching into a respected, performance-based profession that would give teachers the recognition, responsibility, collegiality, support, and significant compensation that the unions want for their members.

There are no shortages of challenges ahead. No shortages of problems for us to solve. But by the same token, there are countless opportunities for us to seize. We must embrace the opportunity to reimagine education and build it back better. We must evolve it to meet the needs of our students.

There is a saying in Spanish, En La Unión Está La Fuerza. It means we gain strength from joining together. In that spirit I look forward to sitting at the table with educators, parents, caregivers, students, advocates, state and local tribal leaders. There is no higher duty of a nation led to build better futures for the next generation to explore.

For too many students, public education in America has been a ‘flor pálida’, a wilted rose. Neglected, in need of care. We must be the master gardeners to cultivate it. We will work every day to preserve its beauty and its purpose….

Toch: That’s going to require a lot of tough love for the nation’s educators, by one of their own.

[Read More: An Educator to Lead the Education Department]

[Read More: Who’s Who in the Education Department]