This piece was published in The 74.

Leaders at selective colleges and universities often say that they want to recruit high-achieving students from low-income backgrounds—but can’t find them. A new program that brings college coursework into some of the nation’s poorest high schools is providing students with college credit and a pathway into higher education. And it’s creating a hybrid model for online and classroom learning that could be adapted more widely amid the Covid outbreak.

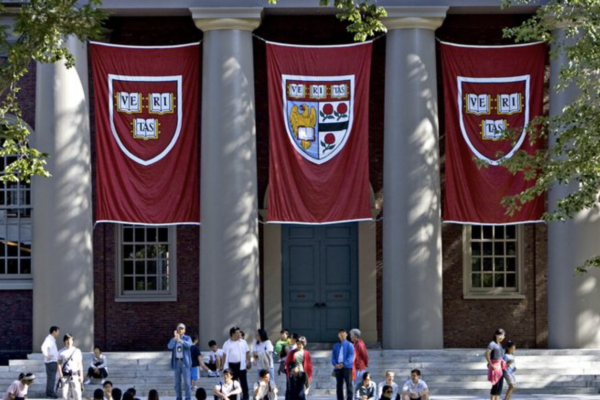

Last fall, 277 students in 11 cities completed the inaugural College-in-High School course, learning American poetry—from Walt Whitman to Kendrick Lamar—from a Harvard University professor. About 90 percent of them received college credit. They include students from an Indian reservation in New Mexico, the Louisiana bayou, and big cities such as New York and Los Angeles.

This semester, about 40 students are getting an introduction to engineering from Arizona State University. Howard University will join the line-up with a class on criminal justice in the fall, when the project is expected to reach a total of 1,000 students in 50 Title I high schools.

In the program, developed by the nonprofit National Education Equity Lab, the college professors’ lectures are delivered online, while a classroom teacher at the high school leads discussion of the material. The students’ papers and tests are sent to the colleges, where graduate students grade them and provide coaching on writing skills.

Part of the project focuses on helping students apply for college: One partner, The Common Application, matches every student with an advisor who helps with applications and financial aid forms. Another aspect focuses on getting the juniors and seniors more familiar with higher education. That includes online conversations with students already in college and videos from former First Lady Michelle Obama and the Reach Higher initiative. Banners outside the high school classrooms proclaim “College in Session.”

[Read More: ‘Fitting In’ and Graduation Rates at UT Austin]

Research shows that first-generation college students often feel like they don’t belong on campus and don’t know how to access the help they need. It also shows that low-income students who could succeed at a selective college often don’t apply.

Earning college credit from a big-name university—with easily transferrable credits—can give students the confidence to apply to better schools. It also gives those schools a sense of what these students can achieve.

Many kids in high-poverty neighborhoods get “nicked up” somewhere in their high school education, says Johns Hopkins University researcher Robert Balfanz, who sits on the Equity Lab’s advisory board. That could be two Ds in 9th grade or a long stretch of absenteeism in junior year that messes up their grade point average. And that can leave college admissions officers unsure whether to take a chance on a student.

The College-in-High School program can help. “What better way to prove that you can actually do college level work than to do college level work,” Balfanz says.

While dual-enrollment programs are expanding across the country, black and Latino students, especially those from low-income backgrounds, are less likely to take part. And the programs that do exist often direct them to community colleges or local institutions—with the unintended effect of discouraging students from reaching for a more selective choice.

The project is in its infancy; there’s no research yet to demonstrate its success in the long-run, but the organizers have learned some lessons. Already they have found that offering the course in an afterschool program is less effective in terms of retention and academic performance than during the school day.

Scaling up the program should be straightforward, says Equity Lab CEO Leslie Cornfeld, a veteran of both the Obama-era Education Department and then-Mayor Mike Bloomberg’s education team. The colleges offer the online coursework at discounted rate, and the tapes from the remote lessons can be used for new classes every semester. In the program’s first year, school districts and state agencies paid some of the costs, and philanthropic partners filled in the gaps.

Amid the funding cuts likely to hit schools post-Covid, the College-in-High School program offers another way to provide high-quality instruction affordably. And it has proven somewhat resistant to the virus: With students already equipped to deal with online content and teachers trained to interact with remote lessons, the program moved online seamlessly this Spring. In fact, its mix of in-person and on-line instruction could be a model for schools that find themselves opening and closing again amid a second wave of the pandemic.

Ultimately, the project offers opportunities for students who need them most, those without the resources, the knowledge, or the confidence to see themselves succeeding in college. Four credits from Harvard go a long way to proving their worth—both to admissions officers and themselves.