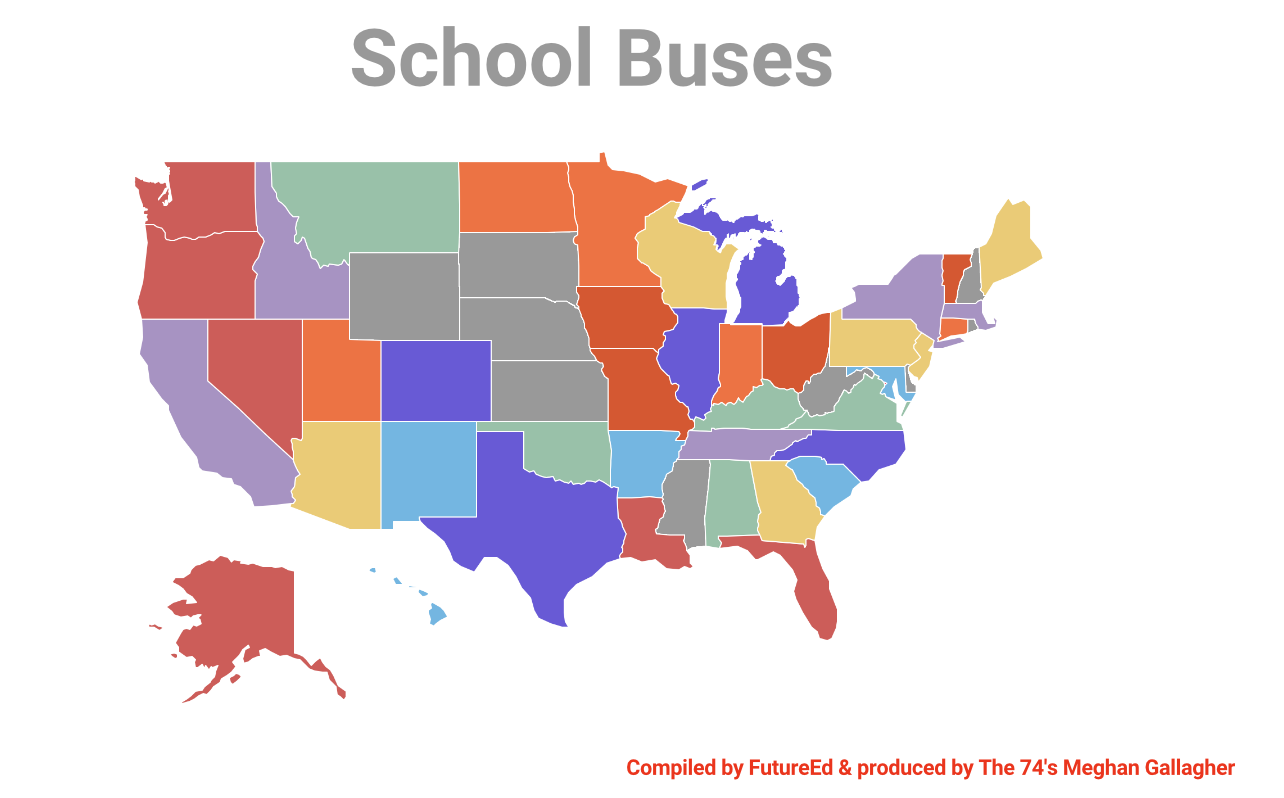

As political leaders debate the merits of reopening schools amid the COVID-19 pandemic, state education and health agencies are thinking through what that would actually look like on campuses this fall. FutureEd reviewed guidance released by states and partnered with The 74 to show what states are advising on six of the most important issues facing schools: meals, school schedules and classroom setups, face coverings, school buses, temperature checks and symptoms, and handwashing. Policy Associate Brooke LePage offers a summary of our findings. And you can click on the maps to learn what each state is advising on each topic.

A screen for COVID-19 symptoms as students step on the morning school bus. A handwashing station as they walk into school. Lunch in classrooms, a brief break from wearing masks. Midday dismissals so buildings can be cleaned before afternoon students arrive. Morning classes at school and at-home learning for the rest of the day.

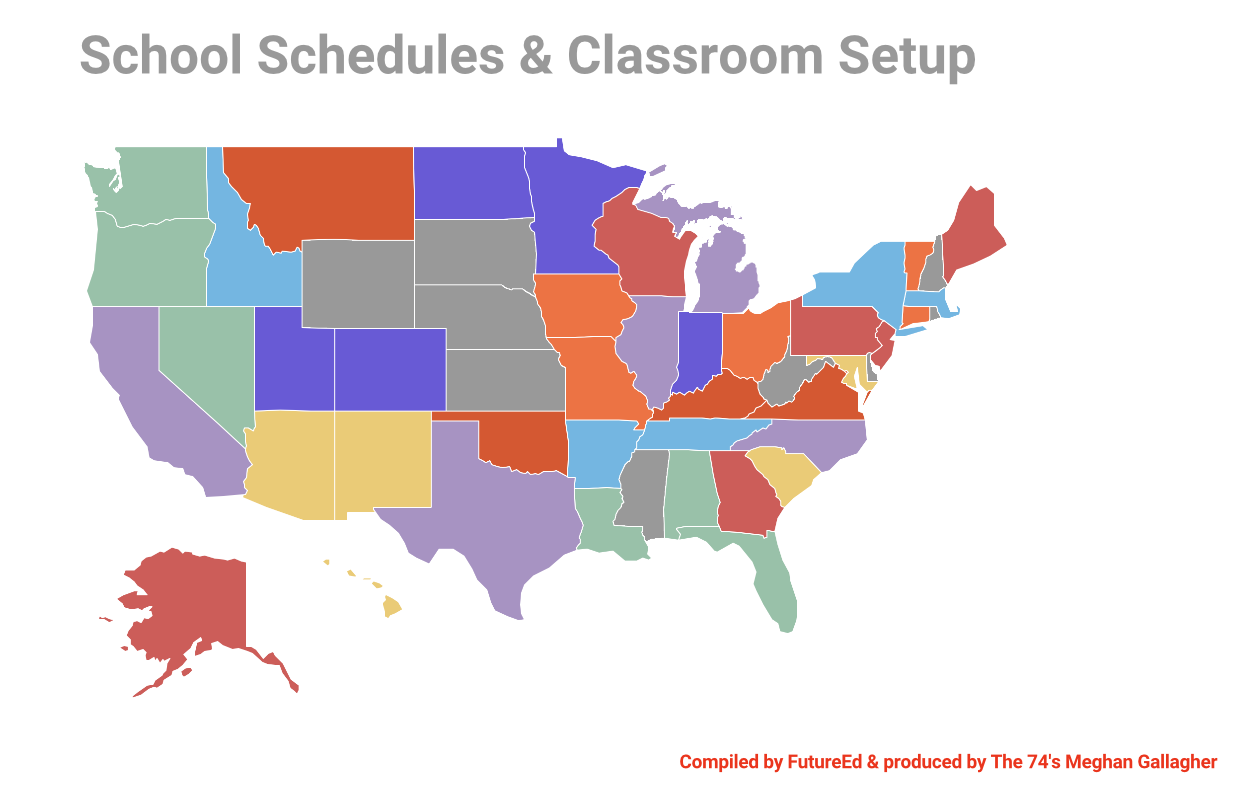

Amid the increasingly politicized debate over whether schools should reopen, states are developing detailed plans for just how to do it. What’s certain is that classrooms and school days will look very different, not only from last year, but also from district to district and from state to state. Virginia will allow classes of 10 students, North Dakota, 15, and Louisiana will move in phases from 10 to 25 to 50. California calls for adding school bus stops to keep too many students from congregating in one spot, while Washington, D.C., recommends one-way sidewalks and street closures to promote social distancing on the way to and from school.

A new analysis by FutureEd of states’ guidance for reopening schools shows that most are following released in April by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations. But as the issue becomes increasingly politicized and Covid-19 cases spike in some regions, the responses will continue to evolve throughout the summer. One thing is clear: States are leaving many of the big decisions — on classroom schedules, face coverings and temperature checks — to local districts.

Of course, even if school buildings do reopen this fall, or are required to do so, as in Florida, not all families will opt for in-person learning. The Ipsos/Axios Coronavirus Index released this week found that 71 percent of parents, including 89 percent of Black parents, consider sending their child to school in the fall a large or moderate risk. A May USA Today/Ipsos poll found 60 percent are likely to pursue at-home learning instead of sending their children to school this fall, and 30 percent say they are very likely to do so.

Pennsylvania’s guidance, which was funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences and developed by the research organization Mathematica, suggests 20 percent of students could stay home voluntarily.

When AASA, the School Superintendents Association, asked superintendents whether their districts would resume in-person learning fall, only 5 percent of leaders answered yes. Los Angeles and San Diego announced this week that they would begin their schools on line, and New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said schools will reopen only if their region’s infection rate is below 5 percent over a 14-day average. All the plans released by states so far call for providing remote learning options.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, which recently published its own education guidance, advises that students return to classrooms in the fall, stressing in a later statement that the local leaders and public health experts should make the final decisions. Others cite the low odds of children contracting the disease or point out that many working parents cannot afford to keep their children home, whatever their wishes.

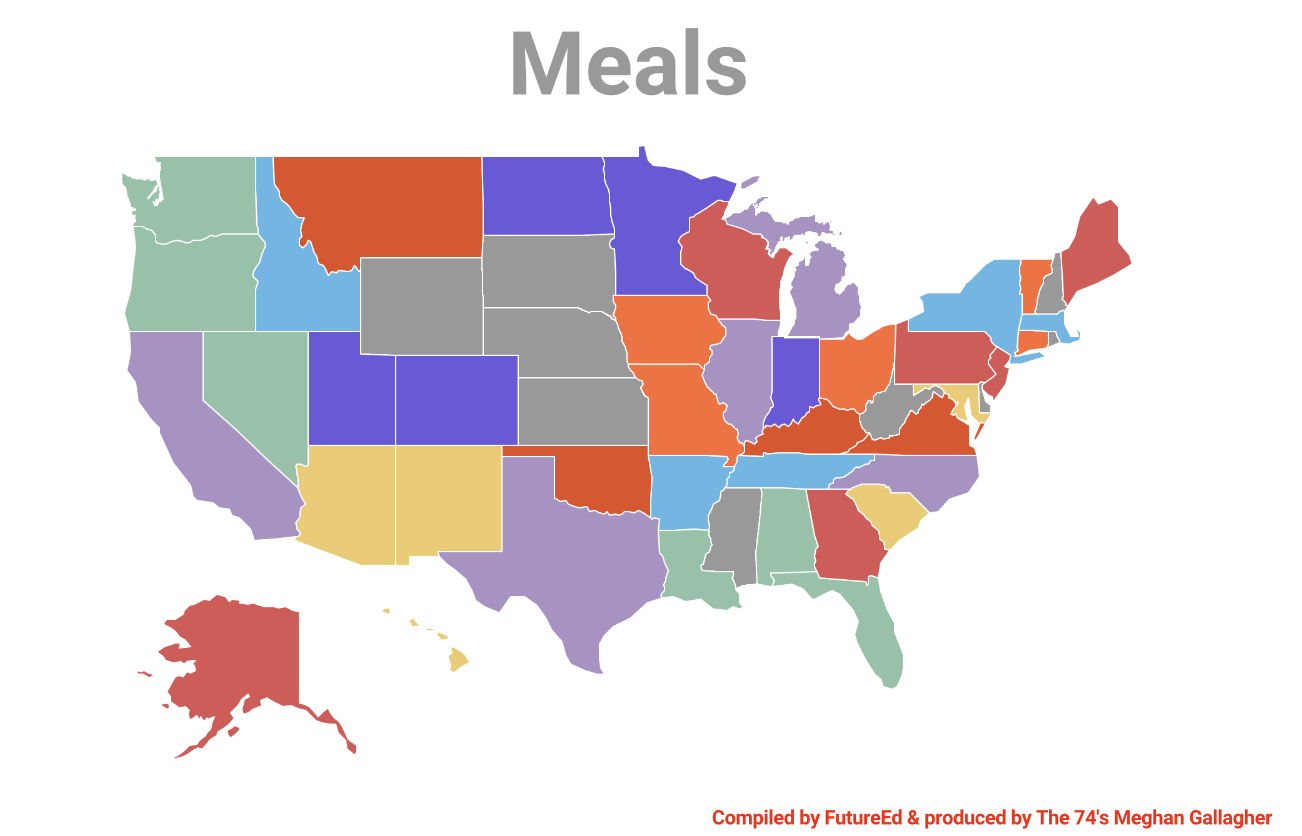

State guidance is relatively consistent in advising districts to have students eat meals in classrooms, spread students out on buses and in class, avoid having students switch classrooms, set new handwashing protocols and use gyms, auditoriums, cafeterias and the outdoors to provide more social distance.

Most provide a range of options on what a hybrid model would look like. These include having students attend school in half-day, one-day, two-day or weekly rotations and arriving at staggered times. All these models would significantly disrupt the traditional structure of the school day.

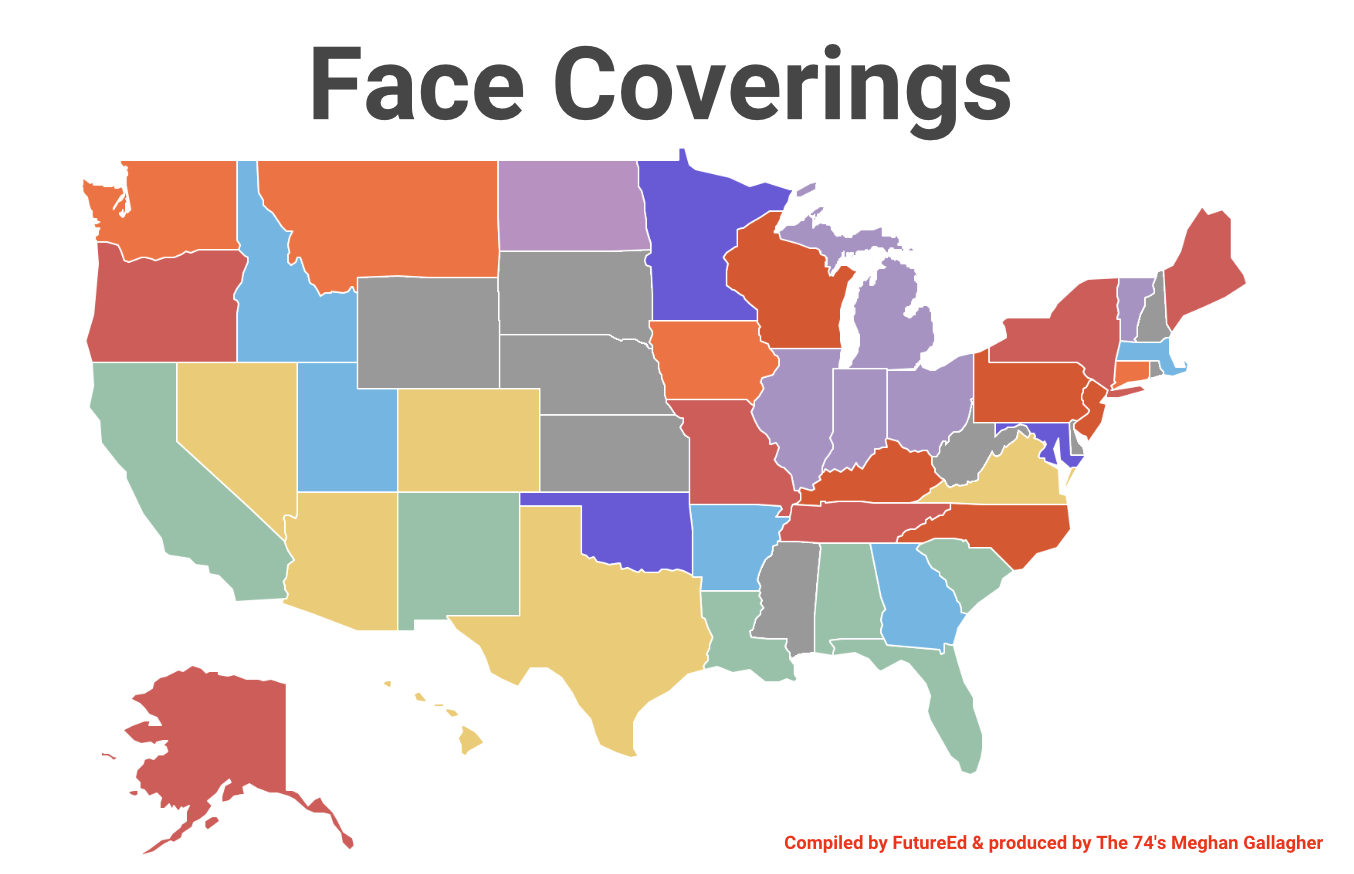

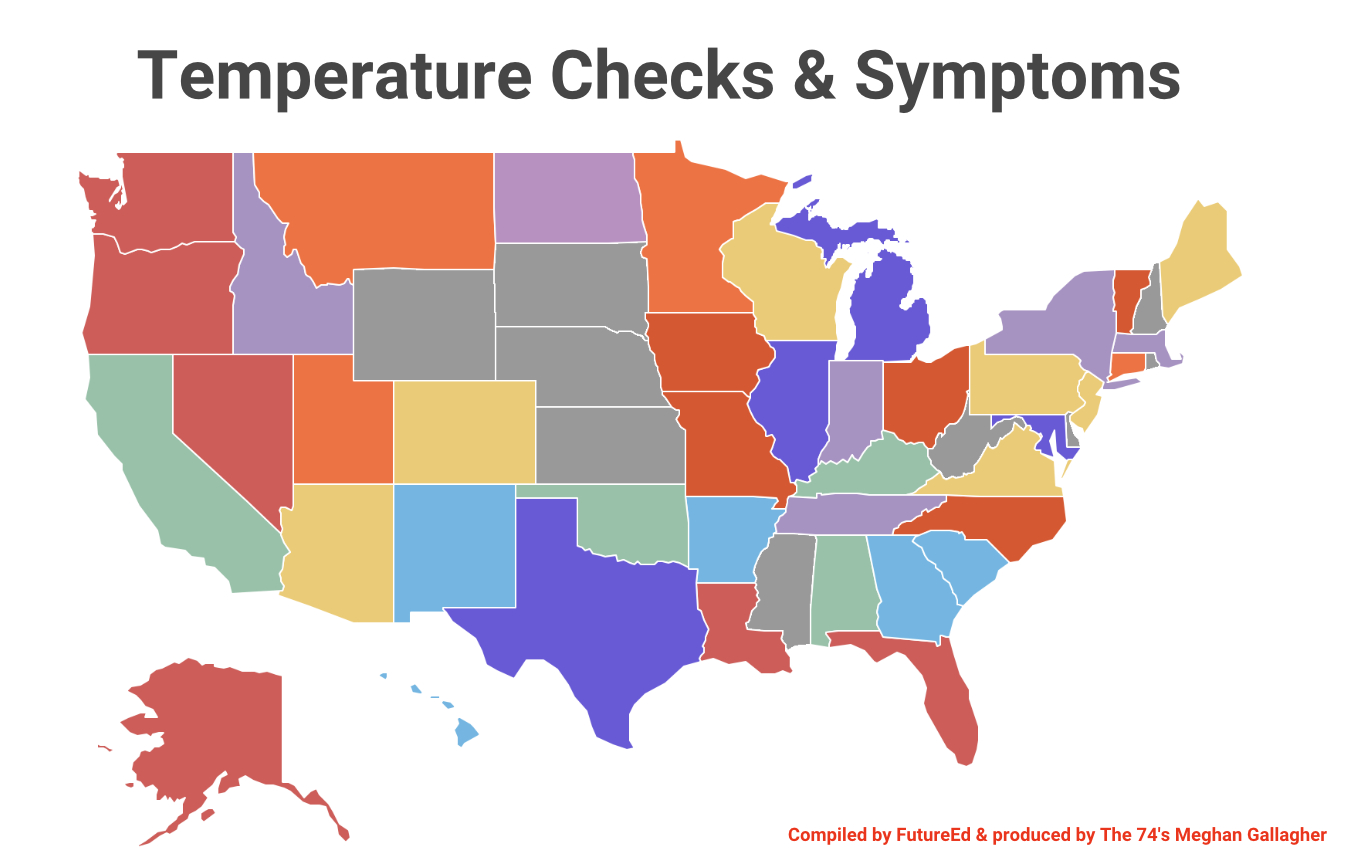

Where the state plans diverge is on policies governing face coverings and temperature checks. South Carolina strongly encourages masks for school staff and suggests districts consider encouraging them for students, while Massachusetts requires them for teachers and staff, and for all students in second grade and up.

Temperature checks require designated staff and thermal scanners. A CDC study of 290 children diagnosed with COVID-19 through April 2 found that only 56 percent had a fever — hardly a reliable result for ensuring school safety. And their new guidance for symptom screens points out that temperatures may be indicative of other illnesses or may be taken improperly, leading to incorrect results.

Because of this uncertainty, state guidance varies considerably. It also sometimes reflects the political divide nationwide. Places with COVID-19 outbreaks early on—New York, New Jersey, Washington state, among them—are among the 22 states urging school districts to require masks. Another 18 states advise districts to recommend mask use, except for young children or those with certain health conditions. Four split the difference—calling for requirements for staff and more discretion for students. Four leave it to districts to figure out their own protocols. And three states led by Republican governors—Florida, Georgia and Iowa—caution districts against mandating anything. In Georgia, where Gov. Brian Kemp has blocked local jurisdictions from imposing mask requirements, the guidance simply calls for allowing students to bring masks from home.

Whatever the guidance, districts can comply only as much as their budgets, buildings and local climates allow. According to an analysis by AASA and the Association of School Business Officials International, the average district of 3,659 students, eight schools, 183 classrooms, 329 staff members and 40 buses could spend nearly $1.8 million to implement and maintain proper cleaning and hygiene protocols — all in the face of steep budgets cuts due to the pandemic.

As a consequence, states are largely issuing recommendations, rather than requirements. At this point, most districts are likely still evaluating guidance and waiting to see how the pandemic unfolds over the rest of the summer.

States are also looking to the federal government for help. In March, Congress approved $13.2 billion in pandemic relief for K-12 schools. The House passed legislation in May calling for another $58 billion for stabilizing K-12 budgets, and Senate Democrats have just proposed $175 billion.

Sen. Lamar Alexander, chair of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, among others, has called for the federal government to help fund reopening costs that he predicts could total $50 billion and $75 billion. Even so, the Senate is not likely to take up another funding measure until late July, leaving little time for states and districts to decide how to pay for the changes needed for a very different return to school.

[Read More: How Do We Reopen Schools?]

Brooke LePage is a policy associate at FutureEd. Editorial Director Phyllis Jordan and Research Associates Caroline Berner and Vasilisa Smith assisted with the research. Meghan Gallagher, a designer for The 74, created the graphics.