The relationship between student poverty and academic performance is well-established: On average, economically disadvantaged students have lower levels of achievement than their peers, a gap that has not narrowed in the past 50 years.

What’s more, when poverty is concentrated in a school—that is, when a significant portion of students in a school come from low-income households—the impact on performance is compounded. A body of research suggests that there is a ‘tipping point,’ somewhere between 50 to 60 percent of a school’s students living in poverty, where performance for all students there drastically declines.

Not surprisingly, schools and districts with high rates of poverty need more resources to educate their students; one recent study found that in some states it would cost three times more per pupil just to achieve average student performance in districts with higher poverty rates than in more affluent districts.

This is no small problem. More than one-third of districts nationwide have schools with concentrated poverty, accounting for 44 percent of all students. Concentrated poverty in schools disproportionately impacts students of color. More money enables school districts to invest in what matters most. Yet when it comes to state funding, districts with concentrated poverty are still getting far less than they need, despite decades of efforts to improve funding disparities.

In many ways, poverty compounds the inequity. While the federal government provides some support for schools with concentrated poverty, communities with more low-income families tend to have less local tax revenue to devote to education. That leaves state funding formulas to address the greater needs of districts with concentrated poverty.

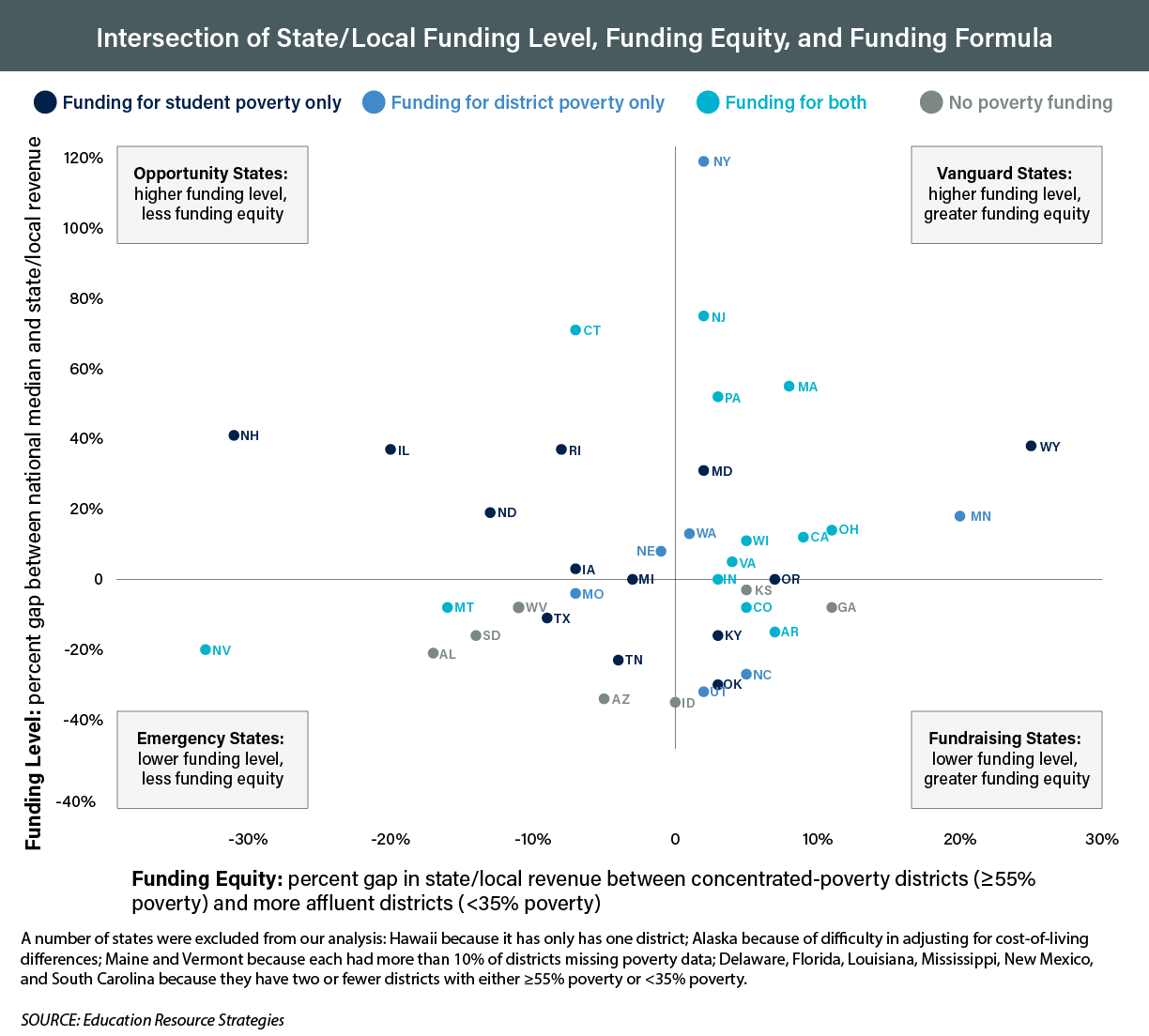

The success in doing this varies dramatically by state: Some states fund their schools more fully and distribute more resources to districts with higher levels of poverty. Another set of states have higher funding levels overall, but don’t address equity. Others have equitable systems, but not much money. And in too many states, education spending is both low and inequitable.

The following graphic reflects our analysis of each state’s funding profile. To assess the level of funding, we looked at how close the state and local revenue in each state came to the national median. To determine the level of equity, we looked at the gap in state and local revenue between districts with concentrated poverty—that is, those where 55 percent or more of students qualify for free and reduced price meals—compared to districts where less than 35 percent are from low-income families. Click here for more on our methodology.

While 41 states have policies on the books that specify additional dollars for students living in poverty and 22 allot additional money for districts with concentrated poverty, in nearly all cases this additional funding is so low that it doesn’t come close to what research suggests is necessary. Also, it isn’t enough to mitigate inequities resulting from differences in local resources.

Adding to the challenge, many states experienced declines in per pupil funding following the 2008 recession. Although revenues are bouncing back in some states, many states and districts still face revenue shortfalls, affecting their ability to invest in essential education resources such as high-quality teachers and principals, rigorous curricula, and targeted student support. And districts with concentrated poverty tend to be hit the hardest since they often can’t rely on local revenue to make up for state cuts.

The right solution depends, in part, on where states fall on the funding spectrum:

Emergency States—Lower funding level, less equity: Boosting education revenue and directing more of those additional dollars to districts with concentrated poverty requires making the case for education as a key driver of a state’s economy and redoing the funding formula with an emphasis on equity. In Arizona, last year’s #RedforEd movement pushed legislators to bolster the education budget, but not nearly enough to address teachers’ low salaries and poor working conditions, and not designed to direct more dollars to districts with concentrated poverty.

While creating additional revenue is a challenge, these states may be able to avoid the political hurdles associated with reallocating resources if they can direct new resources strategically into districts with concentrated poverty rather than shift resources away from more affluent districts. A key solution here is the longstanding practice in school finance reform of increasing funding for underfunded districts rather than expecting affluent districts to reduce their spending levels, a politically unpalatable position.

Opportunity States—Higher funding level, less equity: These states should adjust their funding formulas to enhance their support for schools and districts with concentrated poverty, as well as how those formulas account for local communities’ ability to raise revenue. These states may have a political challenge around shifting dollars among districts.

Illinois historically had the largest funding gap because the state’s system relied primarily on local property wealth; in 2017, a new formula was signed into law, intended to ensure each district’s resources align with student needs, and providing more state money to districts with higher poverty rates.

Fundraising States—Lower funding level, greater equity: These states should focus on raising more revenue to put into education, while continuing to value equity. Currently, most of these states provide some additional dollars for low-income students, districts with concentrated poverty, or both, yet the impact of those dollars varies considerably.

Georgia’s school districts have been underfunded for years, and its formula doesn’t provide additional resources to students in poverty or districts with concentrated poverty; yet its districts with concentrated poverty receive more revenue as a result of its equalization grants, which provide more resources to districts with lower wealth.

Vanguard States—Higher funding level, greater equity: These states are ahead of the pack, and they can do even better. They can lean further into their equity investments to bring the resources that districts with concentrated poverty receive closer to what’s recommended by research.

For example, Maryland, gives districts nearly double the per-pupil rate for students living in poverty—by far the highest of any state—yet this analysis shows Maryland districts with concentrated poverty receive only 2 percent more in state and local revenue than more affluent districts. That’s likely a result of wealthier local jurisdictions raising additional revenue beyond that required in the state formula; the state recently established a commission that is working to determine how to revise the funding formula to provide best-in-class schools for all students.

Funding inequities have long been a problem in public education; the fact that significant gaps still exist speaks to the difficulty of changing entrenched funding structures and addressing the often-politically divisive issue of re-allocating resources to meet student needs. Yet changing this reality is critical to changing the trajectory for students in schools with concentrated poverty.

Nicole Katz is a principal associate at Education Resource Strategies who focuses on district-level strategic resource use and state funding systems.