In the fall of 2019, four high schools in a San Francisco Bay Area district shook up many of their ninth grade math classes. Students had traditionally been separated into more than five math courses by achievement level, from remedial to very advanced, and the district wanted to test what would happen if they combined their bottom three levels into one. Half of the students in those levels were randomly assigned to learn together, and half remained in their traditional tracks so that researchers could compare the difference.

Students in the lowest level who were part of the experiment skipped remedial math and were able to learn algebra with the majority of ninth graders. The experiment also meant that average, grade-level students were learning alongside peers who lacked foundational math skills.

It was risky. Students sometimes end up with lower math scores when they’re pushed to do work that is too advanced for them; that’s why California ended an eighth grade “algebra for all” initiative a decade ago. Grade-level students can also be harmed if teachers try to accommodate weaker students by making the material easier.

But if the heterogeneous class avoided those pitfalls, the new math placement would give hundreds of students with low test scores in seventh and eighth grades a better shot at progressing to advanced math courses and college. Too often, these students feel stigmatized and demoralized. “You’re giving students another ‘at bat’,” said Elizabeth Huffaker, a Stanford University researcher who studied this experiment for her doctoral dissertation.

The results were promising, according to a paper that was made public in October 2024. Half of the remedial students in the mixed class passed the ninth grade algebra course and moved on to geometry with their classmates. The other half still had to retake algebra in 10th grade, which is when they would have taken it anyway, but their test scores in 11th grade were higher than similar students who had learned math in a separate remedial classroom in ninth grade. Eleventh grade math achievement for remedial students who had taken ninth grade algebra was so much higher that the difference was equivalent to an extra year’s worth of math, according to the researchers.

Meanwhile, average students appeared to be unharmed. Those who had been randomly assigned to the new mixed level class had test scores in 11th grade that were no worse than those who had learned Algebra 1 separately.

Some detracking advocates argue that everyone benefits from mixed ability classes, but there was no increase in test scores for higher achieving students in this experiment. The vast majority of students in the mixed-ability classrooms would have been assigned to Algebra 1 anyway and relatively few were low achievers. It’s possible that there’s a point at which the concentration of low-level students becomes so high that it does negatively affect peers, the researchers said.

In between the bottom students and the regular Algebra 1 students, there was a middle group of students who scored just below the cutoff for placement in Algebra 1 and were traditionally assigned to a double dose of algebra in ninth grade. The results were more ambiguous for these students, whose instructional time was cut in half by giving them only a single dose of algebra in a mixed-level class. They were less likely to pass geometry in 10th grade, but they appeared not to be worse off later in 11th grade. “One interpretation is that this was a pretty successful experiment for most students, but if you paired it with more instructional time, it would be even more effective,” said Huffaker. It would be more costly, too, she said.

The Sequoia Union High School District, where this experiment took place, educates a wide range of students. It includes wealthy neighborhoods in Redwood City, Menlo Park and East Palo Alto, and low-income neighborhoods. Roughly a third of the students in the district are poor enough to qualify for the federal subsidized lunch program, and 15 percent are categorized as English learners. Almost half of the students are Hispanic, 11 percent are Asian, and a third are white.

This experiment did not include more advanced students who had already taken algebra in eighth grade or earlier. More than a third of the 2,000 ninth graders continued to be taught in separate geometry or Algebra 2 classes. A handful of extremely accelerated freshmen were in precalculus.

That enabled this limited detracking experiment to avoid the community uproar that had engulfed San Francisco, where advanced students had been prevented from taking algebra in eighth grade and everyone was put into the same ninth-grade math class.

Tom Dee, a Stanford education professor who conducted the math study along with his former graduate student Huffaker, said that this study shows that there are smaller things that schools can do between the two extremes of forcing all students into advanced coursework or barring any students from advanced coursework in the name of equity. “If we accelerate everyone,” Dee said, “it could be harmful to kids who aren’t fully prepared for that acceleration. And if we decelerate everyone, it can be potentially harmful to the achievement of higher performing kids and cap the kinds of things they might do.”

“But it’s not the only arrow in our quiver,” Dee said.

Dee emphasized that this was just one group of students in one school district and the results would need to be replicated in other places before he would recommend the elimination of high school remedial math as a national policy.

Inside the classroom

It’s hard to tell what might have been the key to success in this experiment. It’s possible that half of the remedial students never really needed remediation and they were incorrectly placed because of their middle school math scores. At the same time, the district changed the way it taught in these mixed-ability classes and it could be those changes that made the difference. Better teachers might have volunteered to teach them. These teachers had extra training, and were given an extra non-teaching period each day.

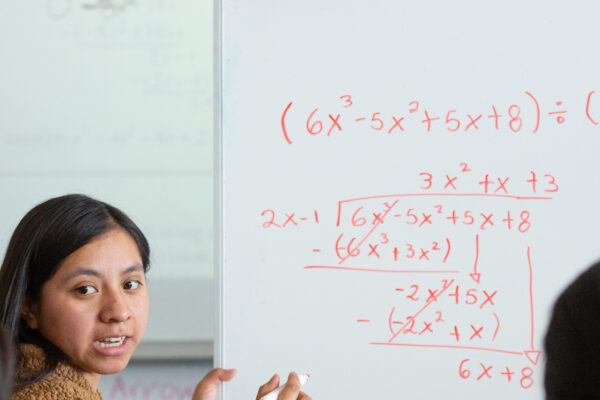

The school handled mixed abilities in an unusual way. Instead of differentiating instruction by giving different practice problems to different students, which is a common approach in U.S. classrooms, the teachers were trained to give the same problems to all students. Victoria Dye, Sequoia Union’s director of professional development and curriculum, told me that the district selected open-ended word problems that even a student with low skills could try, but that also provided a challenge to stronger students. (An analogy would be a game with simple rules, like Othello, which still provides a challenge to expert players.) Dye said that these “low-floor, high-ceiling” problems were selected to supplement the district’s curriculum, which emphasized procedural fluency and computations.

Classroom math discussions took center stage so that students could discuss each other’s analysis. In one exercise, students each wrote down their reasoning and revised it several times. “It’s great because any kid can begin that and improve,” said Dye.

To make time for problem solving and discussion, teachers streamlined the curriculum to emphasize key concepts. That meant cutting some algebra topics. Teachers made their own decisions on how to weave in a review of middle school concepts that students needed for algebra. Dye described this review as happening briefly on a “just-in-time” basis, not a reteaching of a full unit.

Today, remedial math has been eliminated in the district’s main high schools and nearly all students are in ninth grade algebra or a more advanced class, except for students with severe disabilities. The elimination of remedial math doesn’t fix everything. Many struggling students are still failing the subject and need more help. And it doesn’t reduce the huge disparities in math achievement inside school buildings. But it might help a large chunk of the most behind kids, and that’s particularly relevant after the pandemic when even more teens are woefully behind in math.

Jill Barshay is a senior reporter at The Hechinger Report, where she writes the weekly “Proof Points” column about education research and data. This column was initially published by The Hechinger Report.