The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), signed by President Obama in late 2015, requires schools and districts to report the number of students missing too many days in excused and unexcused absences, and 36 states and the District of Columbia have included chronic absenteeism in their systems for measuring school performance under ESSA.

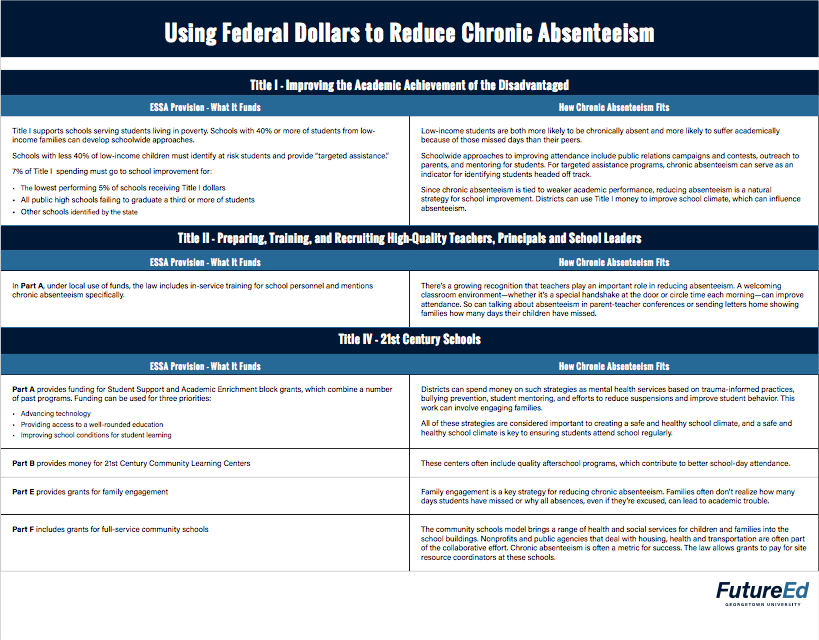

In addition, there are several pots of federal money authorized in the law that states can use to fund efforts to reduce absenteeism, including funds targeted at improving academic success for disadvantaged students, engaging parents and families, and improving “school conditions for student learning.”

Any spending under ESSA must abide by the law’s “supplement, not supplant” rules. If a school district is already spending state and local money on reducing chronic absenteeism, it can’t simply swap in federal dollars and spend the state and local money elsewhere. It has to supplement existing spending.

Also, in some cases, the solutions the schools and districts adopt should be “evidence-based,” a term the Education Department has endeavored to define. It’s also important to know that ESSA recognizes the value of engaging community partners in helping students, explicitly allowing for paying nonprofit and for-profit agencies for needed services.

With these things in mind, let’s look more closely at how law’s provisions could support absenteeism-reduction efforts.

Title I

With upwards of $15 billion to spend annually, ESSA’s Title I is dedicated to “Improving the Academic Achievement of the Disadvantaged.” As such, this money is targeted toward schools serving children living in poverty. As it turns out, these are exactly the students who are most likely to be chronically absent and most likely to suffer academically because of those missed days.

In addition to Title I funds for schools serving low-income students, about 7 percent of each state’s Title I money must be dedicated to school improvement for struggling schools. The law defines these as the lowest performing 5 percent of schools receiving Title I dollars, all public high schools that fail to graduate a third or more of their students, and any other schools identified with low-performing subgroups of students, as defined by the state.

Again, these are likely to be the schools with high concentrations of poverty—and high concentrations of chronic absenteeism. An analysis of New York City elementary schools found a strong and direct correlation between poor attendance and a constellation of 18 factors characterized as “deep poverty.”

This is hardly surprising. The web of challenges facing children living in poverty—housing instability, lack of access to health care, unreliable transportation, and hunger—can make it harder to attend school regularly. And those missed days can erode academic performance. Students who are chronically absent—those missing 10 percent of more of the school year in excused or unexcused absences—often struggle to read well by third grade. They are more likely to drop out of high school and less likely to persist in college. The New York analysis found that schools with high rates of chronically absenteeism typically had lower test scores.

[Read More: Writing the Rules for Tackling Chronic Absenteeism]

Thus, tackling chronic absenteeism becomes a natural strategy both for supporting schools in communities with concentrations of poverty and for turning around schools that are struggling academically. Title I schools where 40 percent or more of the students come from low-income families can develop comprehensive, schoolwide approaches to improving achievement using Title I funds. If a school chooses to do that by reducing chronic absenteeism, there are several approaches that could work: public relations campaigns and contests, outreach to parents, mentoring for students and other approaches. Also, districts can use Title I money to pay for improving school climate, which can influence absenteeism in a number of ways.

In schools that don’t reach the 40 percent threshold, administrators must use Title I money to provide a “targeted assistance program” for students who are at risk of failing to meet the state’s academic standards. In this context, chronic absenteeism can be a powerful indicator for identifying students who need more support.

Finally, low-performing schools that apply for Title I school improvement funds from the state could use those additional funds to reduce chronic absenteeism as part of a school turnaround strategy. However, these funds, unlike other Title I formula funds, must be spent on activities that are supported by strong, moderate, or promising evidence. Connecticut created a helpful guide to evidence-based practices.

Title II

Dedicated to “preparing, training and recruiting” high-quality teachers and administers, ESSA’s Title II formula grant program outlines a series of priorities that local education agencies can pursue. These range from teacher evaluation and recruitment efforts to class size reduction. Much of the section deals with professional development. In that context, ESSA specifically mentions chronic absenteeism as a topic for in-service training using Title II funds, along with a series of non-academic issues considered vital for student learning: safety, peer interaction, and substance abuse.

While tracking attendance has long been the province of the front office, there’s a growing recognition that teachers play an important role in reducing absenteeism. A welcoming classroom environment—whether it’s a special handshake at the door or circle time each morning—can improve attendance. So can talking about absenteeism in parent-teacher conferences or sending letters home showing families how many days their children have missed. Attendance Works has developed a set of training modules to help teachers and administrators.

Title IV

The authors of ESSA stress the flexibility that the new version of the federal law affords state and local education officials. Title IV reflects that with its Student Support and Academic Enrichment grants, which combine a number of past programs into a block grant for states to divide among districts. The grants are designed to pay for three priorities: providing access to a well-rounded education, improving the use of technology to promote academic achievement and digital literacy, and ensuring safe and healthy students by improving school conditions.

The 2018 fiscal year federal budget included about $1.1 billion for these grants nationwide. Local education agencies that received at least $30,000 in grant funding must spend at least 20 percent on well-rounded education and ensuring safe and healthy students. In addition, no district can spend more than 15 percent of their funds on technology infrastructure (though additional funds may be spent on other activities to improve digital literacy).

It is the “safety and healthy” provision where chronic absenteeism has the most relevance. Districts can spend money on such strategies as mental health services based on trauma-informed practices, bullying-prevention programs, student mentoring, and a variety of approaches to reduce suspensions and improve student behavior. This work can involve engaging families.

All of these strategies are considered important to creating a safe and healthy school climate, and a safe and healthy school climate is key to ensuring students attend school regularly. A survey of 25,700 middle and high school students in one urban district found a direct correlation between a poor school climate and absenteeism.

In some instances, students are concerned about safety, either from school bullies or community violence. About 7 percent of high school students said they missed school in the past 30 days out of a fear for their safety either at school or traveling there, according to a survey by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.Likewise, the wrong approach to school discipline can leave students feeling either unsafe or unfairly punished—both of which can lead to chronic absenteeism. In other cases, students stop coming to school simply because they don’t feel connected to teachers, students and the coursework being taught there. Depression and other mental health concerns can keep students from showing up for class.

[Read More: How Did ESSA’s ‘Non Academic’ Indicator Get So Academic?]

Another priority in this grant program—improving the use of technology—might be tapped to pay for software or equipment needed to track chronic absenteeism data. Without good data, regularly updated, schools are often in the dark about the extent of their absenteeism problem or the students who need support. Title I and Title II funds could also be used to help administrators collect and analyze student data.

Beyond the grant funding found in Part A of Title IV, Part B supports 21stCentury Community Learning Centers, which include afterschool programs linked to better attendance. Part E provides grants for promoting family engagement, which when done successfully, can help reduce absenteeism. Parents often don’t realize how many days students have missed or why all absences, even when they’re excused, can lead to academic trouble.

Part F, Subpart 2, includes grants for full-service community schools, which often use chronic absenteeism as a metric for determining success. The community schools model brings a range of health and social services for children and families into the school buildings. Nonprofits and public agencies that deal with housing, health and transportation are often part of the collaborative effort. The law provides grants to pay for a site resource coordinator at these schools.

From its inception, ESSA was designed to go beyond the focus on test scores and academic metrics found in the past version of the law, No Child Left Behind, and consider other factors that contribute to school success. As such, the law recognizes the value of school climate, mental health and other factors related to “safe and healthy students.” Reducing chronic absenteeism becomes both a strategy and an outcome for this focus on improving the conditions in which students are learning.