Among the dire educational consequences of the pandemic, the impact on student absenteeism stands out. The pandemic’s long months of remote learning, hybrid schedules and repeated quarantines frayed bonds among students and between students and educators and fractured routines of attending school. Chronic absenteeism soared to a pandemic peak of 30 percent—more than one in four American public-school students missing more than 10 percent of the school year.

Among the dire educational consequences of the pandemic, the impact on student absenteeism stands out. The pandemic’s long months of remote learning, hybrid schedules and repeated quarantines frayed bonds among students and between students and educators and fractured routines of attending school. Chronic absenteeism soared to a pandemic peak of 30 percent—more than one in four American public-school students missing more than 10 percent of the school year.

Districts and schools have been hard at work to get students back in school more regularly, leveraging an array of approaches including home visits, text messages to parents, community schools, improving the quality of school buildings, and more.

One state, Rhode Island, has gone further. Under the leadership of Governor Daniel McKee, the Rhode Island Department of Education has built a statewide coalition of mayors, business leaders, hospitals and other stakeholders beyond the state’s education ecosystem to get students back to school—a strategy that is yielding impressive early results.

This report, researched and written by FutureEd Policy Director Liz Cohen, tells the story of Governor McKee’s pioneering response to Rhode Island’s absenteeism crisis over the past year, and its potential to help other states and localities address the absenteeism crisis in public education.

We are grateful to Governor Daniel McKee, his staff, Rhode Island Commissioner of Education Angelica Infante-Green and many of Rhode Island’s local leaders for their willingness to grant us the access we needed to tell Rhode Island’s absenteeism story effectively.

As always, Bella DiMarco, Molly Breen, and Merry Alderman of FutureEd’s editorial team did an outstanding job producing this report. And we’re grateful to Overdeck Family Foundation for its support of the project and FutureEd’s ongoing work to help policymakers address chronic absenteeism.

Thomas Toch

Director, FutureEd

On a Thursday in early spring, Daniel McKee stood at the free throw line in the gym at Woonsocket High School in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, ready to take a shot. At 72, McKee was no longer the player or coach he once was. He had come to Woonsocket as Rhode Island’s 76th governor. And a school gym, along with local community centers and anywhere else people gather in the towns and communities of Rhode Island, is the type of venue he likes best.

McKee was in Woonsocket to speak about the importance of school attendance during halftime of the annual Police Department-Fire Department basketball game. And he’d agreed to compete in a friendly free-throw competition with Woonsocket Mayor Christopher Beauchamp.

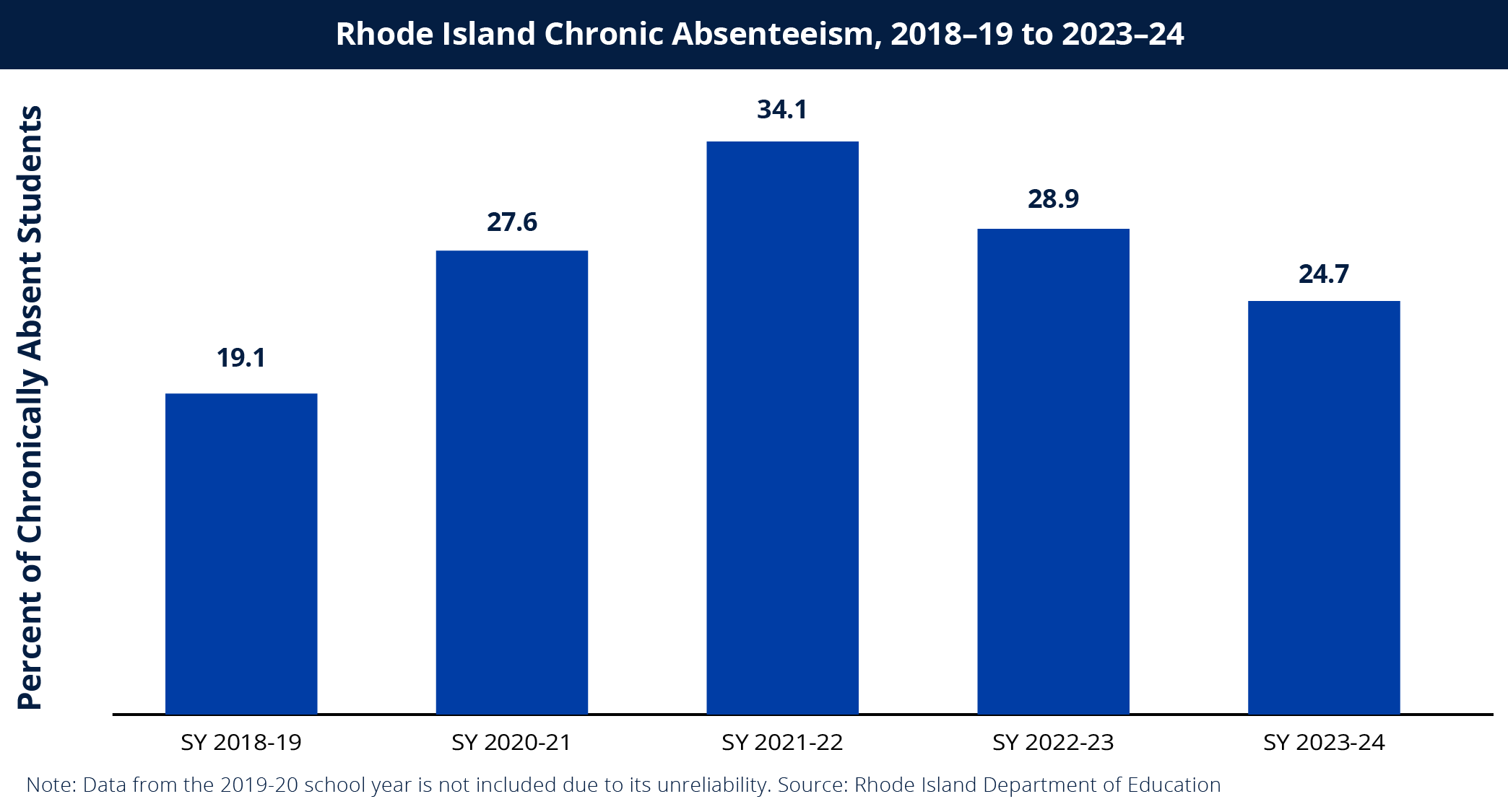

Governor McKee was happy to take his best shots that day, but the outcome he really cared about was raising academic achievement in Rhode Island by prioritizing attendance in every town and school district in the state. Like every state, Rhode Island experienced a tremendous spike in chronic absenteeism in the wake of the pandemic, leaving students less likely to graduate from high school and threatening to depress student achievement well into the future. Chronic absenteeism—missing at least 10 percent of the school year—ballooned from 19 percent in the state pre-pandemic to 34 percent in 2021-22, even after vaccines became widely available and regular in-person school resumed.

In response, McKee launched an unprecedented statewide strategy in 2023 to increase attendance. He began tracking and widely publicizing real-time student attendance data—making Rhode Island the only state to do so—in order to engender a collective sense of urgency among Rhode Island stakeholders. These included not just schools and school districts but mayors, hospital systems, business leaders, and others.

The effort is paying off. Rhode Island’s chronic absenteeism rate dropped to 24.7 percent in 2023-24, the lowest it’s been since the onset of the pandemic. Eighty-nine percent of the state’s 64 school districts lowered their chronic absenteeism rates from the previous year, as did 82 percent of Rhode Island schools.

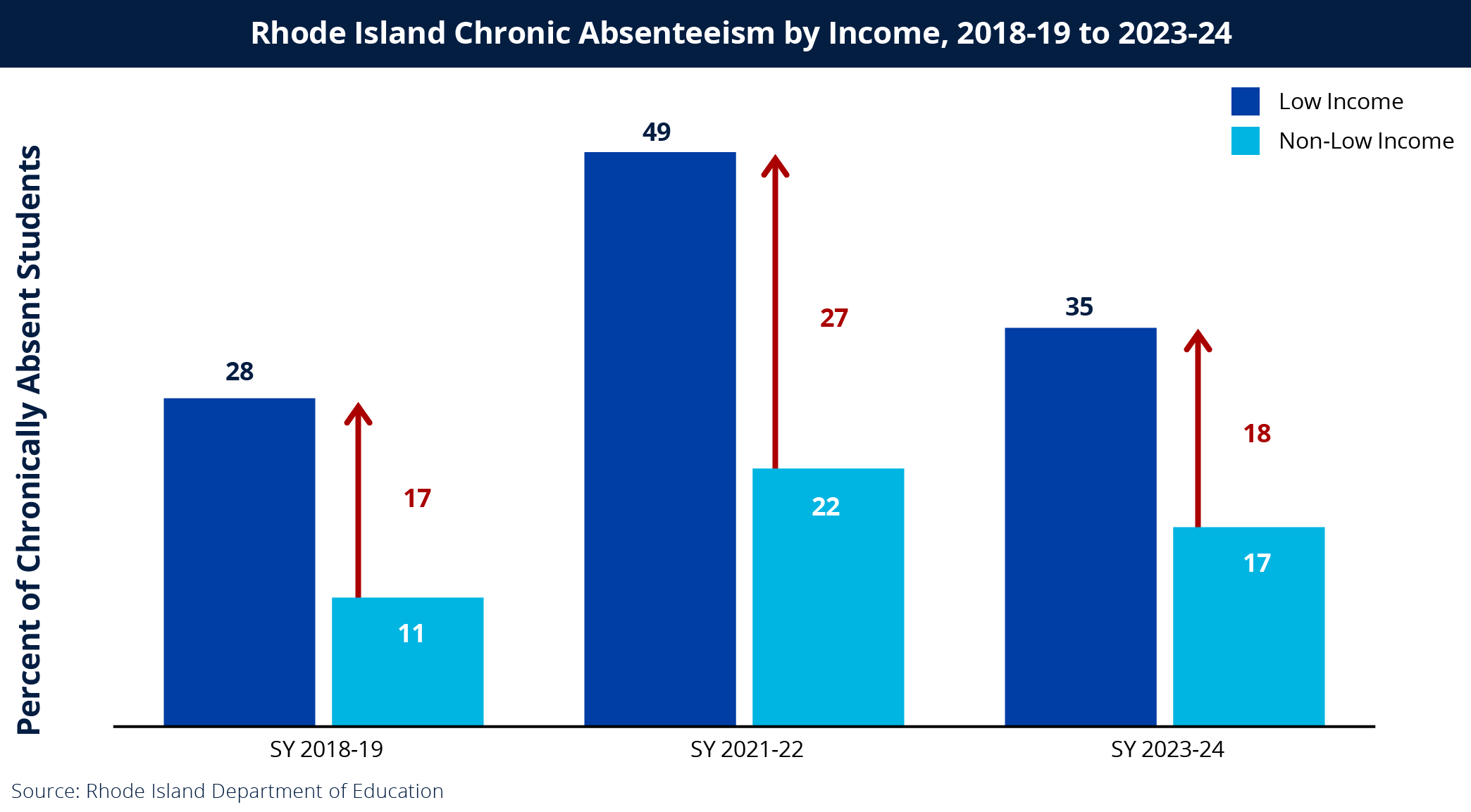

Importantly, Rhode Island has also made strides in closing the absenteeism gap between low-income and more affluent students. In 2021-22, the year the state’s absenteeism rate peaked, almost half of Rhode Island’s low-income students were chronically absent compared to 22 percent of their higher-income peers—a gap of 27 percentage points. Since then, the gap has shrunk to 18 percentage points, suggesting that Rhode Island’s approach to tackling chronic absenteeism is working for its most vulnerable students.

It is too early to know whether Governor McKee’s strategy will ultimately lift student learning in Rhode Island. But its success in bringing students back to school is both a model for other states and a testament to the power of political leadership, data, and community-wide collaboration to address challenges in the education sector.

Changing Habits

Chronic absenteeism has long been a serious issue for American students, driven by inadequate transportation, health problems like asthma, and other challenges. During and immediately after the pandemic, students routinely missed school due to quarantine protocols, exposure to illness, and perceived risk of illness, among other reasons. Many parents and guardians didn’t seem to grasp how much school their children were missing, or that the absences added up to significant lost learning.

But education leaders in Rhode Island and nationally also point to another contributor to the post-pandemic absenteeism spike: following extended periods of virtual or hybrid learning, many students and parents seem to believe that attendance simply isn’t important.

When I spoke with her in her office last spring, Rhode Island State Commissioner of Education Angelica Infante-Green illustrated the problem with an anecdote about a call she made during this past school year to a parent whose child had missed almost three weeks of school in a row. She identified herself only as a representative of the Rhode Island Department of Education and listened to the mother explain that the child had been sick:

“Oh, so you have a doctor’s note?” I asked. And she said, “No, I have just been treating her. She was taking medicine and was sleepy during the day. And then she played video games at night, so she was tired the next day.” When I told her we expect the child to come back to school, the mother said, “She doesn’t listen to me.” What was clear to me is that habits have fallen. People have abandoned the habit of going to school every day.

Governor McKee has bet heavily that casting a bright light on up-to-date absenteeism data can change this troubling new culture.

The idea to publicize real-time data came largely from his own shock at realizing the gravity of the attendance patterns in Rhode Island. McKee has long been focused on education as an important issue, but when he realized that absenteeism had become a significant barrier to achieving the state’s education goals, he sought to create a statewide sense of urgency that matched his own.

McKee’s education department created a public website, the Student Attendance Leaderboard, that displays the percentage of chronically absent students in every Rhode Island public school. The dashboard is updated every night through a direct link between each district’s data system and the Rhode Island Department of Education (RIDE). Two RIDE staff members check the data every morning, looking for obvious errors. On the day I visited the department last spring, Peg Votta, a research specialist at the department and one of the staffers responsible for data accuracy, reported that over 20,000 records hadn’t transferred correctly from the school system in Central Falls, the result of a systems update gone awry. Votta had already contacted the district, and the problem was fixed before lunch.

The leaderboard itself wasn’t new to the department—RIDE had been using a version internally for several years. When McKee asked Infante-Green last year if her department could create a tool that would show every school’s up-to-date absenteeism data, the RIDE team was able to quickly modify the existing edition.

The state data system pushed detailed absenteeism information into every corner of the state and led to some unpleasant surprises for local leaders newly confronted with the information. One municipal leader met with the RIDE team, confident he knew the two schools in his town with no attendance problems. A RIDE staff member recalls the leader describing one of them as a “rock star school” because it had a new facility. “But then we showed him the data,” the staffer told me, “and he said, ‘Oh my God this is a crisis. The schools I thought were fine are the schools that are the most troubling.’”

In addition to the public website, principals have their own dashboards that allow them to look at specific students, see patterns in attendance over a school year or longer, or click a button to send a “nudge.” The nudge, first proposed by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein in their 2008 book Nudge, is a method to guide people in a particular direction without inhibiting their freedom of choice, to suggest a beneficial action without mandating it. Nudging students and families quickly caught on nationally as a cheap and easy intervention to improve student attendance, with research suggesting that it reduces chronic absenteeism by as much as 15 percent, at a cost of about $5 per student per year.

Rhode Island principals can send a nudge either via a text message—automatically delivered in the student’s home language to a parent or caregiver—or a printed letter sent home in the student’s backpack. Text messages are faster, but delivery is only guaranteed if the school has a working cell phone number for a parent. At least 250 of Rhode Island’s 271 public schools have used the nudges offered through RIDE’s dashboards since 2023.

Deepening the Bench

The second part of Governor McKee’s strategy is enlisting local leaders outside of education to help lower absenteeism.

From 2000 to 2012, McKee served as mayor of Cumberland, Rhode Island, where he honed a community-first model to expand and enrich out-of-school opportunities for children. One of his proudest moments as mayor was the public signing ceremony for the Cumberland Education Declaration, a vision statement on the importance of education to the community, followed by the launch of the Mayor’s Office of Children, Youth, and Learning. In 2019, then-Lieutenant Governor McKee shared this reflection on his work in Cumberland: “It’s not just money that gets the [academic] results. It’s the overall commitment that a community … has toward that excellence.”

Education remained a priority for McKee when he became governor in 2021. He began with listening sessions, talking to stakeholders across the state about what could move the needle for students. During these conversations it became clear that attendance had become a stumbling block for other initiatives. Ultimately, attendance became one of three stated goals, along with college financial aid applications and student achievement, in LEARN365, McKee’s education policy blueprint.

The blueprint, framed as a compact with Rhode Island’s mayors, asks municipal leaders to commit to improving attendance along with math and reading test scores. Each signatory agreed to host a community education forum, review data on educational outcomes, and form a Municipal Youth Commission to connect students with leadership opportunities in their hometowns.

LEARN365 also requires a needs assessment for out-of-school programming and emphasizes the creation of ongoing community resources such as after-school tutoring or preschool music classes in community centers and libraries. McKee, a deep believer in the power of community centers, offered grants to build or expand community learning centers to local leaders who signed the LEARN365 compact.

It is not only the substance of the compact that motivates McKee, however—it’s also the symbolism of each mayor committing to improve outcomes for Rhode Island’s students. McKee believes that as each town and region across the state studies its absenteeism trends, identifies where chronically absent students live and attend school, and responds to those challenges, communities will achieve stronger attendance. “What we can do is change the culture of a family’s decision making. Schools can’t do that in the same way that mayors and municipal leaders can,” he told me last spring in his Providence office.

Fully 38 mayors or municipal leaders out of 39 in the state have signed the governor’s compact. McKee’s education policy advisor, Jeremy Chiappetta, says it was easy to get people to sign on. Almost everyone agreed with McKee that education is critical to lifting opportunity for Rhode Islanders. Some valued access to additional resources for their communities, even if they were not politically aligned with the governor.

“When he started saying that this is not just the responsibility of the schools, that changed everything,” Commissioner Infante-Green told me in her Providence office. She believes the governor’s prioritization of attendance matters greatly to the culture shift she sees taking place across the state. “I’m always asking questions—on the radio, in supermarkets, wherever I go. We want everybody to say, ‘Hey buddy, why aren’t you in school? What’s going on? What school do you go to?’ I just think it is a collective responsibility, but it starts with the data.”

Before LEARN365, the only people talking about chronic absenteeism were Rhode Island Department of Education officials and school district leaders. Now, other state officials are addressing the issue. In January, the Rhode Island Secretary of Commerce wrote an op-ed in the Providence Journal aimed at businesses, encouraging them to promote school attendance by taking such steps as employing high school students only after the school day and offering scholarships to students with good attendance. The Department of Health included a question about how many school days a child misses annually to well-visit forms pediatricians must complete. Adds Kystafer Redden, Infante-Green’s Chief of Staff, “Traditionally, state education agencies aren’t interfacing with mayors of cities and municipal folks—that’s just not our bread and butter. But this [effort] has really opened the door to conversation and shifting the way we do business across the state.”

McKee’s personal involvement has spurred this collaboration. McKee’s staff reports that the governor checks the state attendance leaderboard multiple times a day—it’s the default website on his computer—and routinely begins meetings asking if those around the table know what the current chronic absenteeism rates are for schools in their communities. His mantra has become “every home, every day, learning matters.” When a Hollywood film crew rented the statehouse in Providence for six weeks and McKee moved to temporary offices, he took the stack of signed compacts with him.

And no town is too small to matter to McKee. When New Shoreham on tiny Block Island, with its one school and 129 students, signed the compact in June of last year, McKee was there in person to thank the town for its commitment to its children.

Businesses Step Up

Mayors and school districts aren’t the only participants in Rhode Island’s attendance effort. Hospitals are playing a role. In one instance, Hasbro Children’s Hospital, Rhode Island’s only children’s hospital, has added a video on the importance of school attendance to the post-hospitalization care shorts parents watch before their children are discharged.

And business leaders are contributing financial resources to the work.

Tom Giordano leads Partnership for Rhode Island, a nonprofit supported by commitments of at least $100,000 per year by 16 of the largest companies operating in the state. He says research clearly shows that the more hours a student spends in school, the better prepared they are for the workforce, making Partnership RI “happy to raise our hands to help in this effort.” While Rhode Island is a small state, its business presence is not: Partnership RI companies include national behemoths like Bank of America and CVS, regional powerhouses like AAA Northeast, and large local employers like Blue Cross Blue Shield of Rhode Island and Brown University.

In addition to their financial commitment to the Partnership, the chief executives of the 16 companies also form its board of directors. John Galvin, CEO of AAA Northeast, serves as the Partnership’s board chair. AAA Northeast has 3,400 employees serving more than 6 million members across Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and New Hampshire. Galvin describes the business community’s motivation in supporting student attendance as twofold: “It’s a moral imperative and an economic necessity for our state . . . We’re committed to supporting our students so that our businesses can hire more Rhode Islanders today, tomorrow, and into the future.”

The Partnership has funded the production of 25 short videos for the AttendanceMattersRI campaign. Each video features a different Rhode Island leader delivering a lighthearted but clear message about the importance of showing up for school every day. Participants include Governor McKee and Commissioner Infante-Green, as well as congressional representatives, a well-loved sports reporter, a respected pastor, the head of the Rhode Island teacher’s union, and others. The videos, which last less than a minute, air on local television, play on social media, and are widely shared through municipal and other websites. Audio versions play on the radio, and large billboards touting “Attendance Matters” line state highways.

The Providence Plan

The Providence Public School District is Rhode Island’s largest and has faced commensurate challenges. In 2019, after years of struggling to address low academic achievement and troubled management, the district was placed under the control of Commissioner Infante-Green’s office. In the wake of the pandemic, it has built an entirely new approach to attendance guided by Governor McKee’s initiative.

Working with the state education department, the district began by recharacterizing attendance as a crucial issue rather than simply another data metric, and then assigning responsibility for that issue to the Office of Family and Community Engagement. By doing so, the district moved its commitment to improve attendance closer to the families and communities that must also commit to getting their kids to school every day. An important new initiative run by the Office of Family and Community Engagement is the parent ambassador program, through which schools can appoint up to two parent ambassadors to receive an annual stipend of $3,600 in return for approximately 10 volunteer hours each week.

These ambassadors, drawn from local school communities and neighborhoods, provide the Office of Family and Community Engagement with important, typically overlooked information about their communities. The ambassadors keep their ears to the ground at local events and stay connected and responsive to families—learning, for example, whether community members are absorbing the district’s attendance messaging or how well families believe the district is addressing their transportation needs.

Crucially, ambassadors are also frontline workers in the push to convince families of the importance of school attendance. “Our parent ambassadors are all around the school,” Reservoir Avenue Elementary School Principal Cynthia Torres told me during a March 2024 interview. “They’re talking to other parents, saying, ‘You know what? Remember attendance, we need to do this work together.’ So, it’s become a community issue. We’re all going to work to solve it. It’s not just the school leaders or the teacher. No, we’re all going to solve it together.”

Torres says that the ambassadors have also pulled more volunteers into the school—grandparents, neighbors, caregivers fluent in languages other than English—to answer parent questions, read with students, help with filing, serve as mentors, and other activities. Because of the ambassador program, she says these new volunteers now feel comfortable enough to be part of the community and advance the work on ending chronic absenteeism.

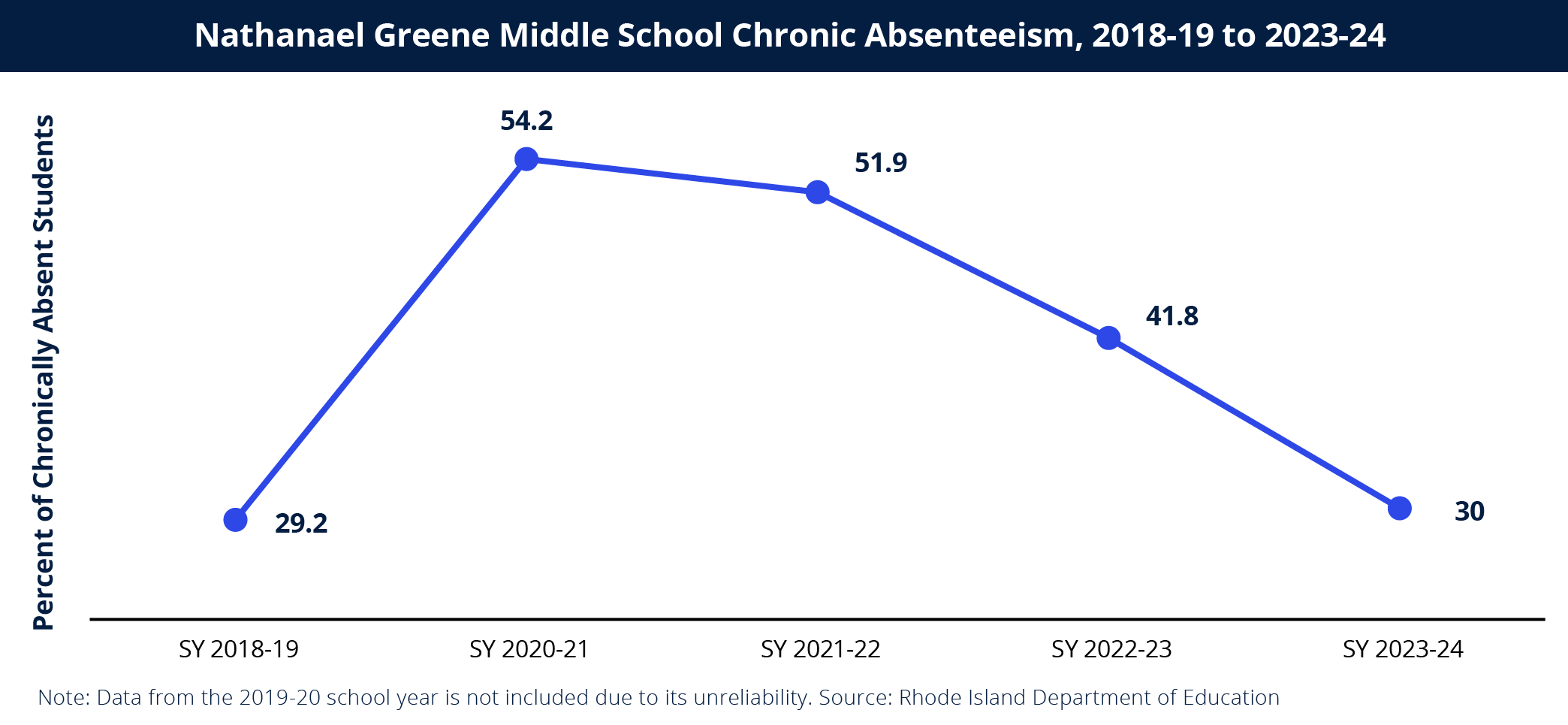

Jackson Reilly has spent his career as a Providence teacher and administrator and currently serves as the principal of Nathanael Greene Middle School, where more than half of the students were chronically absent during the 2020-21 and 2021-22 school years. “Attendance has always been one of the biggest problems we’ve faced,” Reilly told me in a downtown Providence conference room. “But this is the first time it’s truly been a data-driven approach. Last summer, we looked at every single kid who was chronically absent last year and met with every family where the student had missed between 18 and 30 days.”

Reilly and his colleagues asked families to sign attendance contracts for the 2023-24 school year, committing students to attend school regularly. Every Nathanael Greene administrator—including Reilly and his assistant principals as well as counselors—supports five to 10 students, making calls or conducting home visits if a student is absent, and working with families to overcome transportation hurdles. The approach is paying off: by the end of the 2023-24 school year, Nathanael Greene’s chronic absenteeism rate had dropped to 30 percent, less than one percentage point from its pre-pandemic rate.

Thirty-four miles southeast of Providence lies the tiny enclave of Newport. Best known for its long history as a playground for New York’s wealthy families, the town’s small public school district serves a student population three times more likely to live in poverty than the average Newport household. Before the pandemic, about 25 percent of Newport’s roughly 2,000 students met the definition of chronically absent. By the spring of 2022, that number had jumped to 43 percent. “It’s tough to say, ‘Hey, almost half the kids in our school system aren’t showing up.’ That’s jarring,” explains Mayor Xay Khamsyvoravang, who goes by Mayor Xay. “But once it’s out there, I have no choice but to lean into the messaging. That’s what ended up happening as a result of putting that data out there.” Xay credits the attendance leaderboard with opening his own eyes to the attendance problem as well as making it easier to for him to follow the governor’s lead in talking about attendance everywhere and anywhere.

Xay was the first Rhode Island mayor to sign McKee’s LEARN365 compact. He checks the attendance dashboard once a week or so but talks constantly about chronic absenteeism and the importance of regular attendance. When we spoke, he was waiting to deliver remarks at an event celebrating the opening of a new National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration facility in Newport that will result in more than 1,300 families relocating to town. “The federal government has done its job bringing these jobs to my town,” he told me. “My job is to make sure those families have a good public education system, and good housing. That’s what determines whether someone wants to live here, which is what will make my community a community and not a resort.”

According to Xay, the state’s new attendance initiative is central to that work. It has led Xay to amplify the governor’s messaging campaign about the importance of attending school, but also to partner with his school district on steps to reduce absenteeism, including deploying a district staff person with a van to pick up students who miss their morning school bus. And it has led him to enlist local business leaders in the attendance campaign, asking them on the one hand to simply encourage students to be in school, while also challenging them to contribute resources to Newport’s absenteeism work.

The strategy is beginning to pay significant dividends. Newport’s chronic absenteeism rate declined from 41 percent at the end of the 2022-23 school year to 34 percent at the end of 2023-24. While still above the pre-COVID rate of 26 percent, this lower rate represents a significant improvement.

The community-wide strategy for getting students back to school is also playing out in East Providence, a diverse community of almost 47,000 people. Like Mayor Xay in Newport, Mayor Bob DaSilva first learned about chronic absenteeism from the governor. Although he wasn’t sure initially whether the effort would work out, he’s since found that “when you involve the Boys and Girls Club, the library, the senior center, the recreation department, the school department, all working toward making better outcomes for our kids, then everyone’s got a stake in the game. Everyone’s really committed, and they relish the opportunity to get better outcomes for our kids.”

What DaSilva calls a “stake in the game” might also be seen as a collective, unifying goal. The Boys and Girls Club hasn’t started offering different programs and the recreation department is still running the same athletic programs. But a cultural shift has occurred in East Providence—staff at these organizations now have regular conversations about whether the children they serve are making it to school, and they take advantage of after-school and weekend programs to reinforce the importance of daily attendance.

DaSilva and other local leaders say the key is that many community agencies now have a role to play as advocates and communicators on attendance. A former soccer coach, DaSilva likens Governor McKee to a coach who tells everyone that the plan is to score a goal and then lets the players figure out how to get the ball into the net. “He let us, the municipalities, come up with the specifics. But he had the master plan of saying this is where we want go.” Nine out of 10 East Providence schools improved their chronic absenteeism rates in 2023-24 from the previous year.

Hurdles

While many mayors readily signed the LEARN365 compact at the governor’s first request, others were reticent. “Your allies are happy to meet with you,” observes Jeremy Chiappetta, McKee’s education policy advisor. “For people who aren’t your natural allies, it’s a slower process. It takes more explaining.”

That explanation focuses on what McKee and his team call an “outside-in” strategy—their goal is not just convincing mayors that attendance is important, but also that their messaging power is stronger than they realize. Even for early signers of the compact, it was a challenge to help mayors embrace the role of spokesperson for an issue they might not consider “theirs.” Chiappetta notes that throughout the process, there have been leaders saying, “that’s not my lane.”

Those leaders are used to superintendents talking about attendance; either they don’t want to step on district toes, or they don’t know why a mayor should talk about attendance. When we spoke, Chiappetta put it this way:

We would sit down with them and explain that they are validating what schools are already saying, and that it makes a difference … When Mayor DaSilva went on talk radio to talk about attendance, that was powerful. He’s always out in the community talking about issues, but for him to channel his energy and efforts on attendance in particular was new. He really dug into the issue, and I think it showed how powerful messaging from mayors can be.

Few in Rhode Island, and certainly not McKee and Infante-Green, believe talking about attendance and regularly checking absenteeism data are sufficient to completely turn around the state’s school attendance problem. Furthermore, the governor and state education chief see reducing chronic absenteeism as only one step, albeit a crucial one, toward improving student achievement. “Whether students are learning is the ultimate goal,” McKee told me. “We want Rhode Island to be the best in the country when it comes to student learning. Every state should have that same goal.”

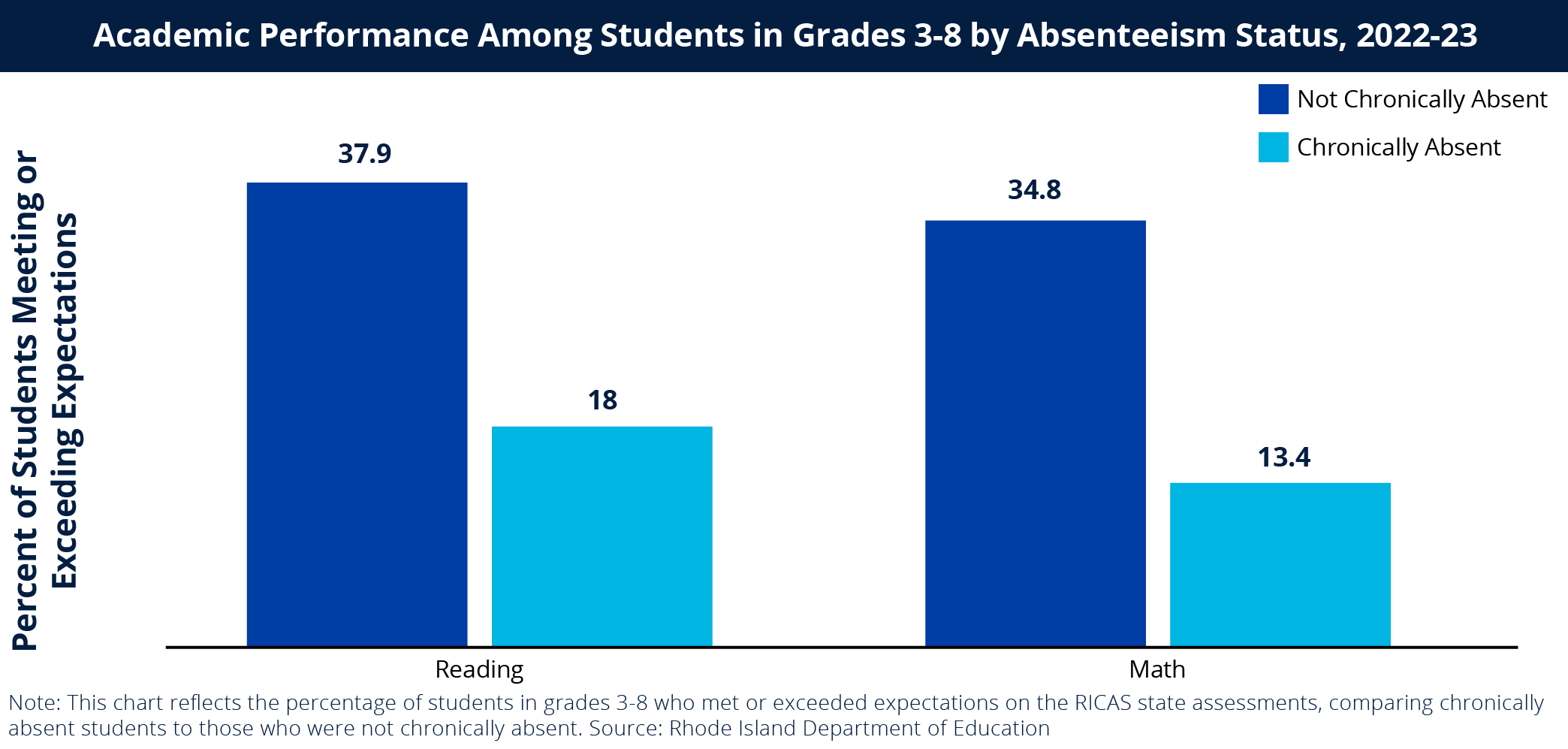

To that end, in addition to the primary Student Attendance Leaderboard, Infante-Green’s agency now produces a wealth of data illuminating the link between attendance and academic achievement, including looking at SAT and state assessment scores and parsing results by students’ economic status, language backgrounds, and other characteristics.

It’s not a surprise that severely absent students learn less, but the magnitude of the relationship between attendance and achievement is striking. Chronically absent students comprised 25 percent of the students taking the state’s standardized math test in 2023, but 40 percent of students scoring at the lowest level. On the other end of the performance spectrum, only 6 percent of students who exceeded expectations were chronically absent.

Rhode Island leaders are waiting for the results of the state’s 2024 standardized tests to learn whether students attending school more regularly has translated into higher achievement. But they’re pleased by another progress marker. In early 2023, just 55 percent of parents responding to the state’s annual survey of public school parents believed that missing at least two days of school a month throughout the school year—the threshold for chronic absenteeism—reduced a student’s chance of graduating high school. By early 2024, less than a year into McKee’s crusade, the number had trended up to 57 percent, a small but important improvement to Infante-Green.

At the Woonsocket High School gym last March, Governor McKee took to the court at halftime to remind the audience that every student needs to be in school, every day. “Education is a community priority,” he told the assembled firefighters, police officers, families, and students. He encouraged Woonsocket to continue building opportunities for students to engage in learning, both by attending school regularly and by attending high-quality out-of-school opportunities in the community.

The governor’s willingness to travel to the high school to highlight the chronic absenteeism crisis in Rhode Island—to recruit allies like Tom Giordano and Mayor Xay, to buttress his messaging with a widely publicized statewide scoreboard on absenteeism—demonstrates the often-untapped power of state leadership to galvanize school reform. It also highlights the fact that many school issues are best addressed by communities working across traditional agency boundaries—an often-under-appreciated concept in education policy circles.