FutureEd Policy Director Liz Cohen delivered testimony to the Council of the District of Columbia on December 12, 2023, focusing on chronic absenteeism and truancy in the District of Columbia public education sector.

Thank you for inviting me to testify today. My name is Liz Cohen, and I am the policy director at FutureEd, a research center at the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy focused on K-12 education.

As of today, 31 states and the District of Columbia have released their chronic absenteeism rates for the 2022-23 school year. D.C. is one of the more recent additions to this list, having just released data on November 30. Unfortunately, of these 32 jurisdictions, D.C. has the highest chronic absenteeism rate for the 2022-23 school year.

We already know that chronic absenteeism is one of the biggest problems D.C. schools face. One-third of schools saw their truancy rates increase during the 2022-23 school year, including 49 elementary schools. Yet we are now almost four months into the current school year, and we are only just seeing data from last year. There is no information about what absenteeism looks like right now to guide policy, practice, or resource allocation.

If I leave you with one idea from my testimony today, I hope it is that more timely public data on absenteeism is an important policy adjustment that will greatly help the District of Columbia address this serious problem.

Before jumping further into solutions, I’d like to provide some important context for D.C.’s chronic absenteeism and truancy statistics.

As you all know by now, D.C. did see an improvement in the rate of students chronically missing school last year. D.C. is moving in the right direction. But when over 40% of students are missing at least 10% of the school year, moving in the right direction might not be good enough.

Only three states on that list of 32 had a higher increase in chronic absenteeism during COVID than D.C., where the chronic absenteeism rate jumped from 30% in 2019 to 48% in the 2021-22 school year. We might thus understand that D.C. has more ground to make up, but we might also ask: why did absenteeism jump more here than other places, and why isn’t it coming back down as quickly as we would hope?

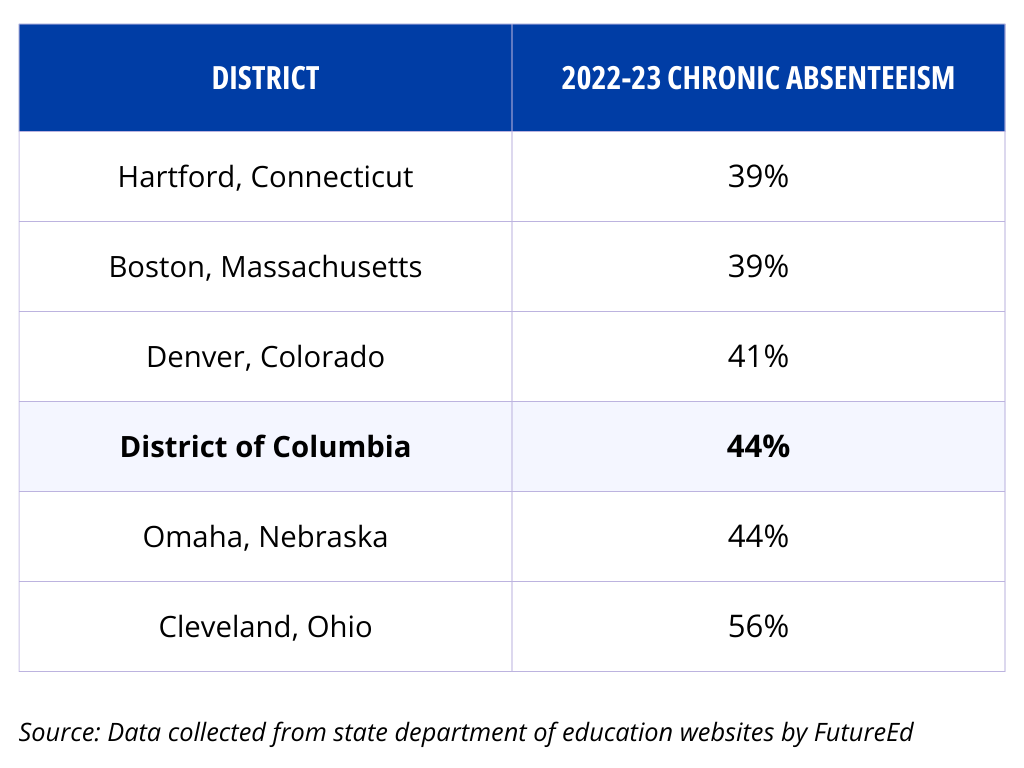

D.C. is different than many states because, of course, it is a city. What happens if we look at other urban districts? I’m including with my testimony a table with the 2022-23 chronic absenteeism rates from five urban districts across five states. This isn’t an official tally of all districts, since not all states have released district-level data—including, I might add, D.C. But by looking at cities with similar size and populations as D.C., like Boston, Cleveland, and others, we can see some districts doing marginally better than D.C., and some, like Cleveland, that are in fact doing much worse.

We might therefore understand that while facing a substantial problem, D.C. is in fact in the same boat as many American cities when it comes to school attendance trends. But that’s hardly encouraging news. There are too many students in D.C. missing too much school.

When it comes to solutions, most of what works boils down to this: relationships and information. Both parents and students need trusting relationships in the school building, and parents need information to understand the true costs of absenteeism.

I already mentioned more timely data as a priority. Let me stress this again: we can’t solve a problem when we don’t know if what we’re trying is working.

In Rhode Island, even as the state waited to release official numbers from last year, the education department launched a public-facing website that shows each individual school’s current absenteeism and truancy rate, updated daily directly by district data systems. A solution like this preserves the state’s ability to validate the full year’s data while ensuring everyone in the broader community has current attendance data at their fingertips.

Council, the Deputy Mayor, and others could also potentially work together to answer the very fundamental question of why absenteeism rates remain so troublingly high. We can’t solve a problem when we don’t understand its root cause. We can hypothesize many things, but it would behoove the District of Columbia to talk to parents and students across the city, in formal and informal ways, to understand why school attendance behaviors have changed so much since the pandemic.

Similarly, we need to bring schools together across DCPS and the charter sector to understand what’s happening and what’s working. Take the examples of Jefferson Middle School and Two Rivers Public Charter Middle School. Both had a 49% truancy rate last year. But Jefferson improved that rate by 14 percentage points from the previous year. Two Rivers saw their truancy rate increase by over 22 percentage points in the same year. Both schools now have the same truancy rate, but for very different reasons and are on very different trajectories. What can these schools learn from each other’s successes and challenges?

My organization, FutureEd, has written extensively on state- and district-level solutions to attendance. Some of them, like requiring attendance teams for schools who aren’t improving absenteeism rates, are important, but also expensive and can be challenging to implement. D.C. should certainly consider these ideas, but while deliberating, the city could begin with some low-cost, low-effort solutions.

The most common low-cost approach is one D.C. is already taking, using nudges to communicate with parents about their child’s attendance. This is the work that the DME’s office is leading with Everyday Labs. For about 7000 chronically absent students who received this intervention last year, their attendance improved such that they were no longer chronically absent. Importantly, it only costs the city about $5 per student. It’s true that there was no impact on about half of the participating students. But if you consider the cost as $30 per student for those 7,000 kids, that is a decent return on investment that should be continued.

Another low-cost action is better health messaging. Qualitative data suggest that parents are more likely to keep kids at home for perceived illness since the pandemic, even when in fact the child could be at school, especially in elementary school. Our partners at Attendance Works developed new health guidance with the National Association of School Nurses and Kaiser Permanente to help parents understand when they can and should send their child to school and to help teachers understand when children can and should stay in school. The D.C. Department of Health could work with OSSE to adopt a version of this guidance for D.C. schools.

Chronic absenteeism doesn’t get fixed overnight. But there are evidence-based solutions which, when paired with more rapid data and a better understanding of parent and student behaviors, should help the District of Columbia get all kids in school every day. Thank you.