Zahava Stadler is project director of the Education Funding Equity Initiative at New America and has researched and written on school finance reform for Education Trust and EdBuild.

The Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER), the $190 billion fund established to help schools respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, has put school funding back in the national spotlight—a valuable opportunity to think about a critical issue in new ways.

There has been much progress over the past several decades in increasing education funding and directing resources to students with the greatest needs through state and federal school aid. And ESSER funds have been a vital, if temporary, response to students’ heightened challenges during the pandemic.

But these improvements have been built on an unsound foundation. Policymakers continue to rely heavily on local property taxes to fund public schools, leaving many students, especially those from low-income backgrounds and students of color, in under-resourced school districts that cannot offer them the advantages provided to their more privileged peers. We need a new school finance agenda, one that addresses the fundamental problem that schools can’t be engines of social and economic mobility when they place students on such unequal footing.

An Unsound Foundation

Forty-six percent of public school funding came from local sources in 2020 and property taxes contributed roughly two-thirds of that local share. But school districts’ access to property tax revenues varies widely because those serving areas with high property values are able to draw on a richer tax base to raise more local money at lower tax rates, while districts with low-value property tax bases are much more challenged at raising funds locally. The result is that so-called high-poverty districts receive 5 percent less funding from state and local sources than districts with low concentrations of poverty nationally, and districts serving the most English learners receive 14 percent less than those with the fewest—despite their students having far more resource-intensive needs.

And in many states the equity picture is far worse than the national averages suggest. Consider Connecticut. It’s among the wealthiest states in the nation, with one of the highest levels of income inequality. The state’s most affluent school districts raise almost triple the amount of per-pupil funding from local sources than the state’s highest-poverty districts do—$18,936 in local funds per pupil compared to $6,802.

Given the connection between property values and neighborhood affordability, the students who lose out tend to be those from low-income backgrounds. And the problem has a strong racial component. Many years of American discrimination against Black and Latino homebuyers has suppressed the property wealth held by families and communities of color. Since the school district map is layered on top of neighborhoods shaped by this history, districts serving many children of color are more likely to be disadvantaged by a school funding system rooted in local property taxes.

In response, most states employ equalization policies—mechanisms that allow districts to tap a combination of state and local dollars to reach a calculated “formula amount” of funding.These efforts help, to a point. But the inequality persists because so much of districts’ local property tax revenue exists outside these policies, in a kind of school funding Wild West. Again, Connecticut exemplifies the problem. Its highest-poverty districts receive $14,698 per pupil in state education aid, while its wealthy districts receive $5,257. But that still isn’t enough to bring funding levels to parity—the high-poverty districts end up with 11 percent less than their wealthy peers—let alone to meet students’ needs.

That’s because in Connecticut, as in nearly every state, school districts may raise “extra” dollars beyond the state formula’s target amount, usually subject to no equalization requirements at all. The result is a school funding landscape in which massive amounts of local money are completely ungoverned by equity-conscious policy. District property tax revenues may amount to just 30 percent of total public education spending nationally, but they’re responsible for a much larger share of the persistent funding gaps between school systems—and especially the gap between districts that serve predominantly students of color and those that do not.

Building Barriers

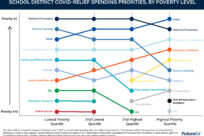

The inequities are even greater advantage in the realm of school facilities, an undervalued ingredient of student success that’s typically financed overwhelmingly with local dollars. Because school facilities financing usually sits outside the main state funding formula and is not subject to any equalization efforts, and since historical disinvestment in school buildings is so expensive to redress, students from low-income communities are at an extreme disadvantage. Districts’ choices regarding the relatively unrestricted ESSER dollars reflect the extent of the problem. High-poverty districts have been much more likely than their affluent peers to use the federal aid to make physical plant upgrades.

The problem they are addressing—and that is still far from solved, despite the ESSER investments—is not merely cosmetic. Extensive research shows that academic achievement is linked to the physical learning environment. Students are more frequently absent from schools affected by infestations or mold, for instance, and scores on tests are lower when they’re taken on hot days in schools without air conditioning. Students should not have to learn in substandard facilities simply because their parents can’t afford a home in a high-priced neighborhood.

And there’s another detrimental consequence to the gaps in local fundings between rich and poor communities: Local money is generally unrestricted, giving school leaders in low-wealth districts far less flexibility in addressing student needs. Federal dollars, in contrast, usually have many strings attached to ensure they are spent on intended student groups. Some state funding comes in the form of flexible per-pupil aid, but much also comes through limited-use grants or reimbursements for specific costs.

As a result, the wealthiest districts, with more local money at their disposal, have the greatest latitude, while high-need districts face the most restrictions. By parceling out dollars to high-need districts in limited-use ways, we tie the hands of those closest to the kids who need the most support and push them to focus on reporting and formal compliance (often tying up funds to pay for entire departments focused on Title I administration) rather than on innovating to meet students’ needs. When high-need districts have flexible dollars available, as they have under ESSER, they can try things that go beyond the standard state-prescribed educational program, like hiring and training family engagement specialists, providing intensive tutoring to the students most impacted by the pandemic, and incentivizing teachers to fill hard-to-staff roles and provide extended instructional time.

It should not require a global health emergency for districts to be given the room to do what’s best for their students. And while it is legitimate for states to implement policies meant to ensure strong budgets or evidence-based uses of funds, these policies should apply equally to districts regardless of their wealth. Flexibility should not be a luxury good.

Solutions

A small number of states have taken important steps to curb or even eliminate the impact of local wealth differences on school budgets and students’ experiences. These and related approaches can point the way toward a more equitable funding system.

Pool funds at the state level

Differences in local tax bases only matter when districts raise and keep funds locally, within the borders of individual school districts. This issue doesn’t arise in Hawaii or the District of Columbia, each of which operates as a single school district. States that have more traditional school district structures can also eliminate the problem by requiring all school taxes to be collected at the state level (as Vermont does) or collected locally but deposited in a state pool for allocation (which Nevada has recently moved to do). As long as state dollars are distributed through a formula that appropriately accounts for differences in student and community need, pooling dollars at the state level can be a powerful way to eliminate inequity.

Limit local dollars

Even when districts keep some funds locally, that only causes inequity when property-rich districts are able to raise funding that exceeds the state’s formula amount. Wyoming is the rare state where school districts are limited to raising the amount of local funding called for in the state formula. Districts must contribute the proceeds of a 2.5 percent property tax toward their schools; they cannot raise less or more, and if the tax yields more than a district’s formula amount, the extra revenue is used by the state to supplement its distributions to other districts. This policy leaves no room for unequal local funding amounts to affect schools’ operations budgets. This approach faces steep political challenges—Wyoming only achieved it under pressure from a court ruling—but it is well within states’ powers, and is among the clearest ways to level the local-tax-base playing field.

Redraw School District Boundaries

The most ambitious, and likely most controversial, approach would be for states to redefine the meaning of “local” in “local school funding” to the benefit of all students. The boundaries of a school district determine more than the area and set of students that its schools serve. They also define the taxing jurisdiction from which a school district raises its local funding. Drawing a district border, then, is one of the most powerful ways to determine what resources will be available to which students.

Today, districts are often drawn in ways that entrench existing problems like residential segregation and inequality, rather than designed to best serve all students in diverse and well-resourced classrooms. But these borders are often the result of historical arrangements or the result of local, often self-interested initiatives to redraw borders.

Unlike with electoral districts, we have neither a norm nor a legal requirement to redraw school districts to ensure more equal governance as populations grow and change. Instead, though state lawmakers have the power to shape and change these boundaries, they rarely exercise it. State laws govern how school districts can and should be drawn. State lawmakers should take a far more active role in ensuring that the school district map produces equitable outcomes.

They could require processes that aim for districts to encompass heterogeneous student populations and be supported by roughly similar local tax bases. No state currently does this systematically. But several states do intervene when school district border changes are proposed. Arkansas and California, for instance, require that new school districts not be drawn in a manner that would hamper racial integration, and six states set requirements so that border changes don’t result in a worse or unsustainable financial position. An extension of these policies would be for states to proactively draw school district borders that produce a more equitable funding system for all students.

States and the federal government have taken important steps over the last several decades to improve the fairness of their distributions and to target funding to student need. But by rooting the school finance system in local property taxes, we have created a situation in which the very first layer of school funding is tied to community wealth rather than to student need, and even the best state allocation policies can only partially compensate for that underlying problem. It’s time to work on solving the problem at its source. No parent should ever have to say, “I can’t afford to live in a neighborhood where my child can go to a good public school.”