Once relegated to those dry, dull school board discussions about facilities, ventilation is having a moment. President Joe Biden mentions it nearly every time he talks about reopening schools. Congressional leaders number it among the important safety improvements that justify billions in Covid relief aid. It makes sense since Covid is an airborne disease, with the virus literally hanging in the air.

But the need to spend some of the windfall of new federal funding on system upgrades and overhauls extends beyond helping students return to school safely: Research suggests that ventilation systems have a surprisingly significant impact on student achievement.

As many as 36,000 schools nationwide needed to upgrade their heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems pre-pandemic, according to a 2020 U.S. Government Accountability Office report. With billions flowing to schools under Congressional Covid relief packages—and another $100 billion promised for school repair and construction projects under Biden’s infrastructure proposal—now is the time to address the backlog.

Classrooms that are too hot can impact learning, according to a 2018 study led by Harvard University’s Joshua Goodman. The research team found that hotter school days in the previous year were linked to lower results on the PSAT, a finding that was particularly troubling for disadvantaged students. For every one degree Fahrenheit of increased heat, the amount of learning dropped by 1 percent; air conditioning helped to mitigate the problem.

[Read More: Perspectives on How Schools Should Spend Covid Relief Aid]

Of course, classrooms that are too cold can also make learning hard. After days of students huddling in freezing classrooms, dozens of Baltimore schools were forced to shut down in January 2018.

Opening windows can help dispel Covid particles in the classroom air, but can complicate student health in other ways, especially if the air outside is polluted by industrial sites or heavy traffic. Air pollution can exacerbate asthma and interfere with brain development, as well as lead to increased school suspensions and absences, several studies show.

A 2020 study led by American University assistant professor Claudia Persico found that children in Florida who lived within two miles of an uncleaned Superfund site had increased rates of cognitive disabilities, school suspensions and repeating a grade. The problem disproportionately affects schools serving children living in poverty.

Poor air quality and poorly regulated temperatures in school also contribute to absenteeism, especially for students with asthma and allergies. In a 2013 study led by Mark Mendell at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, researchers studied 150 classrooms in 28 California schools for two years. They estimated that updating classroom ventilation systems to state standards could bring a 3.4 percent decline in illness-related student absences.

[Read More: Now is the Time to Future-Proof Our Schools Against Outbreaks]

Many districts and states have taken the obvious first step in addressing the challenge: assessing school building needs. The state of Michigan is offering a free HVAC inspection program, and more than 100 schools have replied to their voluntary survey. This could be a model other states should consider.

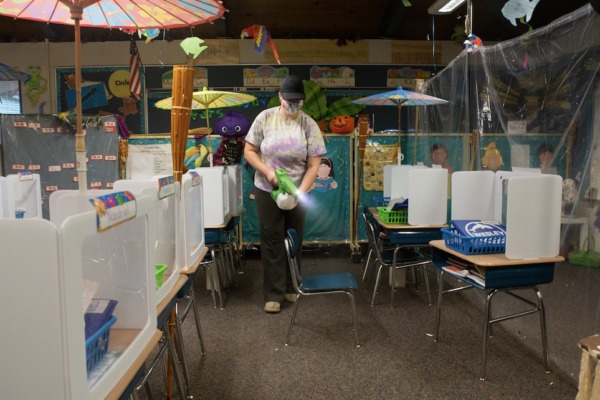

Some school districts have gone low-tech. Philadelphia Public Schools purchased 3,000 fans in preparation for reopening schools in February. Others are investing in higher-quality air filters and UV lights.

Districts using federal relief aid for facilities projects must follow state and federal procurement rules on competitive bids and wages. And American Rescue Plan funding must be obligated by September 2024.

But making these investments now is likely to pay longer-term dividends. “It’s not just a Covid thing,” says Memphis Scholars Executive Director James Dennis of his charter schools’ HVAC investments. “It’s about making our buildings healthier overall.”

[Read More: What Congressional Covid Funding Means for K-12 Schools]