Campaigns of mass vaccination against infectious diseases represent one of the most successful public health interventions in history, yielding increased longevity, equity, and economic growth. But this success has a downside.

Many families now take for granted that their children are safe from diseases such as diphtheria, measles, and pertussis, also known as whooping cough. This complacency, together with fears about vaccine safety, has depressed immunization rates in recent decades, thus increasing danger to those in a community who are susceptible to the diseases: infants too young to have been vaccinated, children exempted from vaccination, the medically frail, and a share of those children and adults who received vaccinations yet lack immunity—no vaccine is 100 percent effective. In the case of rubella, fetuses in the wombs of women who may themselves have immunity are in danger during an outbreak.

Where is the danger of disease outbreak greatest in the U.S.? The answer depends in part on parents’ school choices.

While all 50 states and the District of Columbia have mandatory school immunization requirements for traditional public, charter and private schools, the vaccination rates are lower in some places for charter and private schools. What’s more, homeschooling is notably disconnected from immunization policy. Twenty-six states with 750,000 homeschooled students place no immunization requirements on homeschooling families, and of those states with some requirement, only Minnesota, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee expect parents to furnish proof.

States’ immunization requirements have withstood numerous legal challenges, with the Supreme Court ruling in the 1905 case of Jacobson v. Massachusetts that mandatory vaccination programs constitutionally preserve public health. For perspective, this ruling came more than 50 years—a couple of generations—before the zenith of the polio scare that rattled the country from the 1930s to the 1950s.

Requirements have evolved over time with advances in science, and they represent the most efficient lever available to state governments for ensuring “herd immunity,” the concept that if most members of the community are vaccinated, a disease cannot spread. But there’s trouble in the herd.

A well-publicized 2015 outbreak of measles linked to Disneyland in Anaheim, Calif., is symptomatic of faltering herd immunity in many parts of the country, and it has become the poster-child of outbreaks. By definition, an outbreak of infectious disease involves an agent (e.g., a virus) and enough susceptible hosts to sustain its spread. Outbreaks can span multiple states and tend to trace back to a single international traveler.

The Geography of Risk

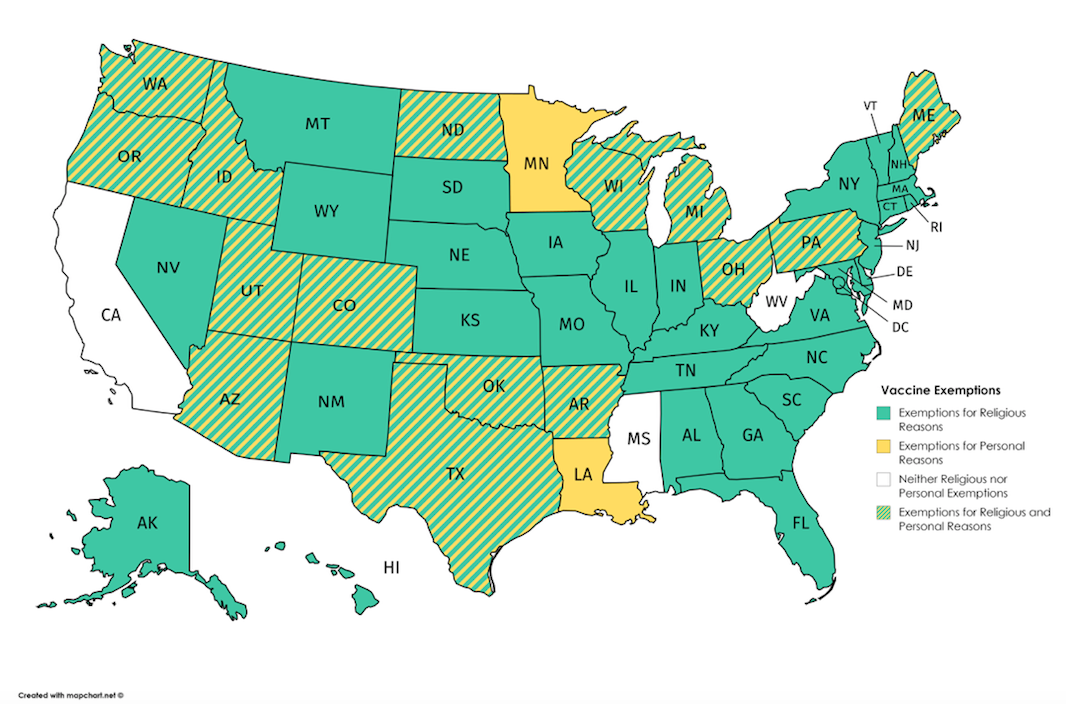

State school vaccine requirements draw from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommendations for infants and children, which include 10 distinct vaccinations, some staggered over time, against 14 diseases. All states allow exemptions for students who cannot tolerate one or more of the required vaccinations for medical reasons, an exemption that is rarely used. And all but five states—California, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, and West Virginia—allow for exemptions based on religious belief.

Additionally, 17 states allow parents to opt their children out based on so-called philosophical or non-religious personal belief. According CDC data for the 2016-17 school year, median elementary school rates of belief-driven or non-medical exemptions for enrolled kindergartners ranged from a low of .5 percent in D.C. to 6.5 percent in Oregon.

The geography of outbreak risk can be sketched roughly using publicly available data on vaccine-exemptions. Public health officials set target school-vaccination rates based on the estimated share of the population that must have immunity to a disease such that the herd has protection from an outbreak. These shares vary by disease, but typically fall in the 90 to 95 percent range for a highly contagious disease like measles. Thus, 95 percent is a prudent overall target for schools, and this is the federal goal set by the CDC for kindergartners. Allowing for a generous 1 percent for medical exemptions, we’d like to see no more than 4 percent of students exempted by belief, religious or personal preference. The national median elementary school rate of exemptions for enrolled kindergartners is about 2 percent.

Washington state was right on the line for the 2016-17 school year with a median elementary school rate of belief-driven exemption for kindergartners at 4 percent—half of schools above, half below. Further over the line were Nevada (4.3%), Maine (4.8%), Arizona (4.9%), Utah (4.9%), Alaska (5.2%), Wisconsin (5.2%), Idaho (6.2%), and Oregon (6.5%). This means that half or more of all elementary schools in these states might not be doing enough to ensure their own community’s herd immunity. No data appear for Colorado, Illinois, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, West Virginia, or Wyoming in the CDC’s 2016-17 vaccine exemption report.

Nationally, private schools have significantly higher rates of exemptions, a 2014 article in the Journal of Pediatrics reported. The report did not address charter schools, which are publicly funded. But more recent state figures suggest that both charter and private schools have higher rates in some places.

Consider Arizona. Sometimes called the “Wild West” of charter school policy, the state is one of six states where charter schools account for more than 10 percent of public school enrollment. The state’s Empowerment Scholarship Account program subsidizes private school tuition.

Its school immunization statute allows exemptions for both religious and personal belief. And it’s among 12 states—the others are Arkansas, Idaho, Maine, Minnesota, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Utah—exhibiting a worrisome trend identified in a paper published recently in PLOS Medicine, a scientific journal. In these states, the proportion of families claiming personal exemptions has increased since 2009, and this trend is behind increasing non-medical exemption rates over the same period. In Arizona for the 2016-17 school year, these non-medical exemption rates stand at 9 percent for charter schools, 8 percent for private schools, and 4.2 percent for traditional public schools. Arizona’s publicly available data don’t account separately for religious and personal exemption.

Washington state is another troubling example. Its non-medical exemption rates for kindergarten students enrolled during 2016-17 rose to 8.4 in private schools and 3.5 in public schools (traditional public and about a dozen charter schools reported together), respectively. Among private schools, the exemption rate breaks down to 8.1 for personal belief and 0.3 for religious concerns. For public schools, the split is 3.3 and 0.2 percent.

Not surprisingly, both states are called out in the PLOS Medicine paper as the home of “hot-spot” metropolitan areas: Phoenix, Seattle, and Spokane. These areas have such high rates of non-medical vaccine exemptions that herd immunity is very tenuous. Moreover, neighborhoods in these areas that contain schools with extremely high exemption rates can be considered hot-spots within hot-spots, or to to use the archipelago analogy, particularly exposed peaks on islands vulnerable to outbreaks.

California’s story is quite different. Its median school rate of non-medical vaccine exemptions among kindergartners in the CDC’s 2016-17 school year exemption report was a mere 0.6 percent. Matched in apparent safety by Alabama, and surpassed only by D.C., this rate represents a vast improvement over those reported in the immediately preceding years. From 2008-09 to 2015-16, the belief-based exemption rates in the state’s charter, private, and traditional public schools hovered around 8.5, 4.5, and 1.8 percent, respectively. What happened in the wake of the 2015 measles outbreak is the basis for the first of four recommendations that follow from this geography of risk.

Four Recommendations

The 17 states still allowing personal exemption should follow the lead of California, which dropped the personal exemption in 2016. (California also put a halt to religious exemptions, but elected officials in other states may be wary of tangling with those for political reasons).

Second, states should commission independently produced, public-facing reports that detail trends in vaccine exemption down to the school and neighborhood levels; requirements placed on parents, including homeschooling ones seeking exemptions; qualifications of school or medical personnel involved in the exemption process; and increased monitoring for exemptions among homeschoolers.

Third, all states should collect kindergarten vaccination coverage data. Only 10 states and D.C. have subscribed to these standards, but many metropolitan areas and communities straddle state lines that outbreaks don’t honor.

Fourth, Congress should direct the departments of Education and Health and Human Services to form a joint task force to guide and monitor states’ progress on these recommendations, and perhaps analogous ones concerning pre-schools and institutions of higher education.

Less than 15 percent of the U.S. population has any memory of the warehouses full of people living in iron lungs or the race to develop a vaccine against polio in the 1950s, the kinds of image and drama that helped the country sustain satisfactory rates of vaccination against disease for decades. Hopefully, it won’t take a massive outbreak, or even a country-wide epidemic of a preventable disease, to bring vaccination rates—national, state, and local—back into safe territory.