With billions to spend in Covid-relief money, school districts and charters in every region of the country have made hiring and paying academic staff their top priority. Summer learning and upgrades to ventilation, heating and air conditioning systems remain popular investments, based on the number of localities planning to pursue such options. And while the internet is rife with stories about public schools using federal relief aid for athletic facilities and other seemingly extraneous expenses, the problem appears to be less prevalent than recent headlines would suggest.

These are among the findings of a FutureEd analysis of the Covid-relief spending plans of more than 5,000 school districts and charter school organizations in 51 states, local education agencies serving some 74 percent of the nation’s public-school students.* Most of the local agencies in the sample are school districts.

The analysis covers districts and charters receiving $83 billion of the $122 billion in Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER III) funds provided under the American Rescue Plan and offers the most comprehensive picture to date of local and regional Covid-relief spending. Burbio, a data service that measures school openings and spending, gathered the local plans from a range of public sources and sorted the proposed spending into more than 100 categories.

[View the charts and resources pages]

The ESSER funding was distributed via the federal Title I aid formula, which supports low-income students. As a result, some school districts serving impoverished communities have received more than $10,000 per student in Covid-relief aid while others have received little or no funding.

Local school districts and charters have wide latitude in using the funds, as long as the spending is geared toward reopening schools safely and helping students recover from the pandemic. States must monitor local spending, and the federal government can audit district and charter school spending, as well.

[Read More: Financial Trends in Local Covid-Relief Spending]

FutureEd identifies national spending trends and patterns in the four U.S. Census Bureau regions, since the demographics and educational profiles of the regions vary. The national trends that emerge from the analysis include:

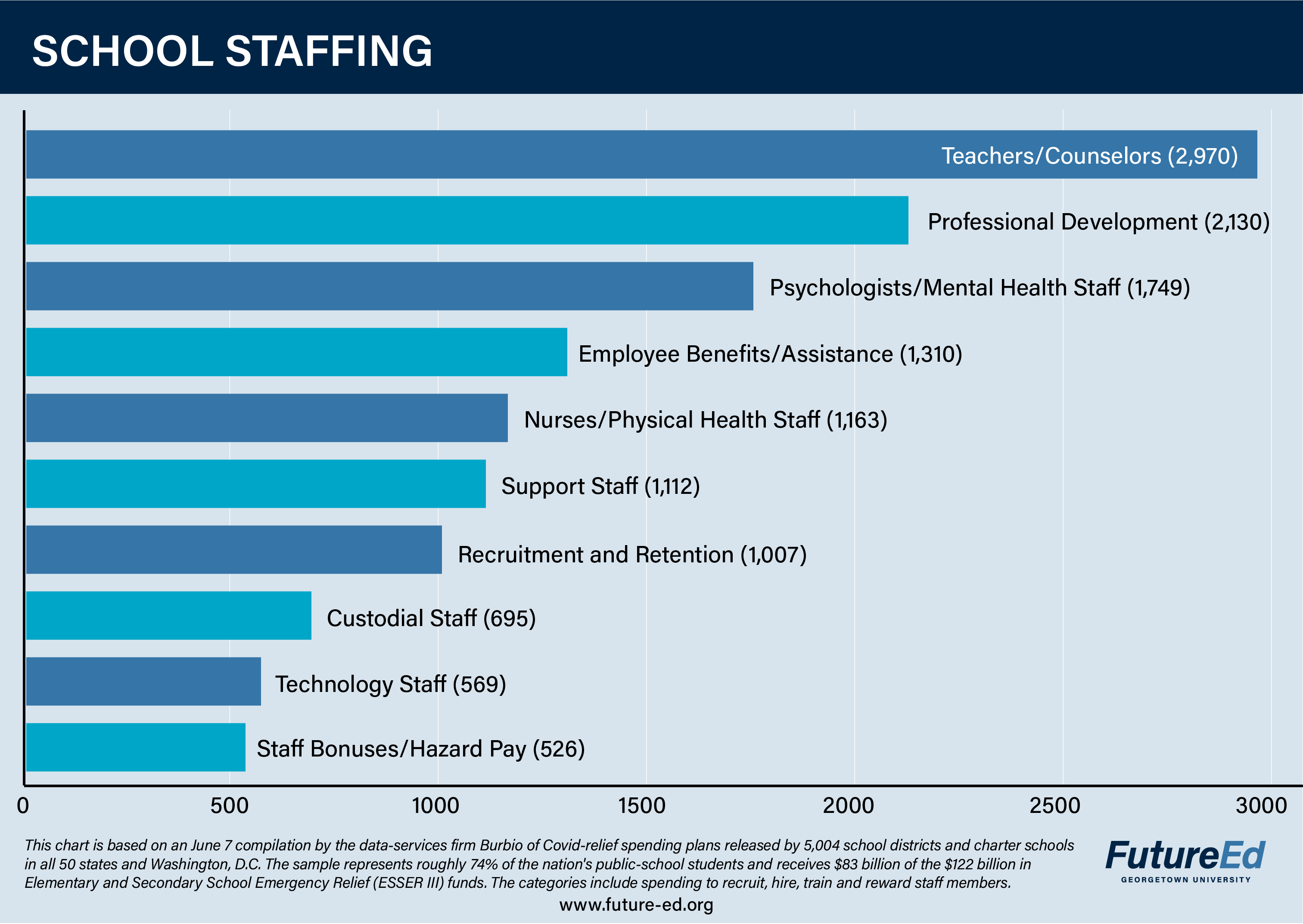

Staffing

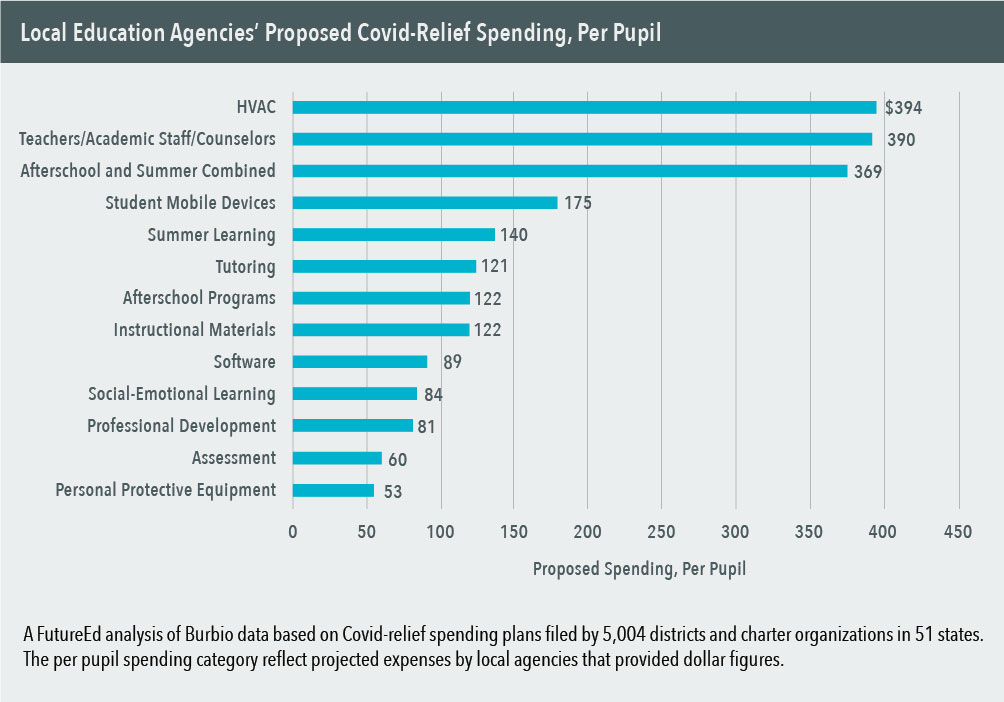

About 60 percent of the school districts and charter organizations in the Burbio sample are planning to spend Covid-relief funds on hiring or rewarding teachers, academic specialists and guidance counselors, making this the highest or second highest priority in each region of the country. Despite concerns about how to sustain such spending when the federal aid runs out in 2024, districts and charters expect to invest an average of $390 per pupil on teachers and other instructional staff.

About 60 percent of the school districts and charter organizations in the Burbio sample are planning to spend Covid-relief funds on hiring or rewarding teachers, academic specialists and guidance counselors, making this the highest or second highest priority in each region of the country. Despite concerns about how to sustain such spending when the federal aid runs out in 2024, districts and charters expect to invest an average of $390 per pupil on teachers and other instructional staff.

About 11 percent local education agencies in the sample to provide staff bonuses or incentive pay, while more than 40 percent plan to pay for training for existing staff members, averaging $89 a student. Bridgeport Public Schools in Connecticut is using $16 million of its $100 million in relief aid to hire new teachers, assistant principals, instructional supervisors, and aides, but will also offer a “teacher leader” stipend for experienced instructors who can guide others. Mission Achievement and Success—a two-campus charter school serving more than 2,000 K-12 school students in Albuquerque, New Mexico—is spending more than half of its $6.6 million allotment on its teachers, including hiring additional special education instructors and math and reading interventionists.

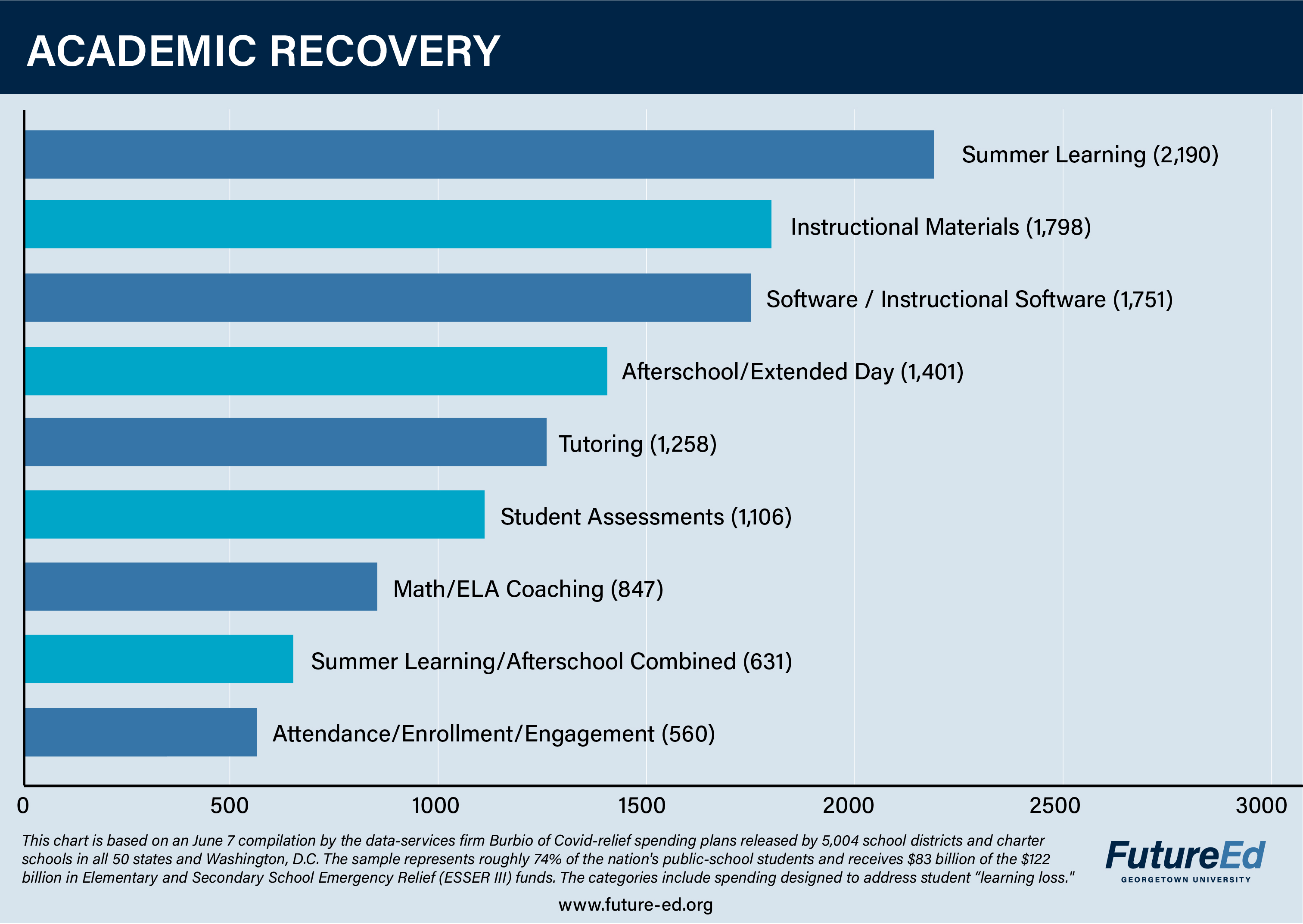

Extending Learning Time

Summer learning and afterschool programs are emerging as key strategies for helping students recover academically from the pandemic’s impacts. More than 40 percent of the school districts and charter schools in the sample plan to spend Covid-relief money on summer programs while about 30 percent plan to fund afterschool learning opportunities. Another 12 percent include summer and afterschool in a combined listing.

Summer learning and afterschool programs are emerging as key strategies for helping students recover academically from the pandemic’s impacts. More than 40 percent of the school districts and charter schools in the sample plan to spend Covid-relief money on summer programs while about 30 percent plan to fund afterschool learning opportunities. Another 12 percent include summer and afterschool in a combined listing.

Among the districts and charter schools that include spending figures, the average was $123 per student for summer learning and $122 for afterschool programming. In Washington, D.C., the KIPP charter school network has earmarked $1.7 million for a summer-learning initiative for its 6,800 students. Georgia school districts, in particular, are budgeting significant amounts toward extended-day programs. For example, Gwinnett County Public Schools is proposing to spend $127 million or nearly half of its federal allotment on afterschool and summer programs; Fulton County Schools is budgeting $98 million or 58 percent of its ESSER III money for summer learning.**

The investments align with the American Rescue Plan’s requirement that at least 20 percent of district-level ESSER III funds go toward evidence-based practices reducing student learning loss. And state education agencies are required to spend at least 1 percent of their ESSER III funds on summer learning and 1 percent on afterschool programs. Somewhat fewer local school agencies, about 11 percent, plan to increase spending on attendance, enrollment and engagement activities to get more students to participate in the regular school day and year.

Tutoring and Assessments

Tutoring, which research has found to produce a substantial return on investment if implemented effectively, is another popular approach to helping students recover from lost learning opportunities during the pandemic; about a quarter of localities are earmarking funds for this strategy, and another 17 percent are planning to fund math and English coaching. In Tennessee, where the state legislature last January established a statewide ALL Corps tutoring initiative, 68 of the 84 local Covid-spending plans submitted to the state include funding for tutors. Chicago Public Schools is spending $25 million of its $1.8 billion ESSER allotment to train 850 literacy tutors. The Houston Independent School District, roughly half the size of CPS, is making a bigger bet, budgeting $113 million for tutoring, roughly 14 percent of its relief funding. One small district in Arkansas, Parkers Chapel, is dedicating its entire $630,000 ESSER allotment to tutoring. Average spending planned for tutoring is $140 per student among the districts and charters in the Burbio sample that provided dollar figures.

Additionally about 36 percent of local agencies are planning to spend on instructional materials and 35 percent on software for instruction and other purposes. The Granite School District in South Salt Lake City, Utah, for instance, plans to put $7.5 million of its $97 million allotment on expanding online learning opportunities for students at different skill levels. Richmond Public Schools in Virginia is devoting $65 million, more than half of its ESSER III total, for a literacy push that includes hiring new staff members, training existing teachers, tapping extended-day partners, and purchasing new instructional materials, software, and books.

Despite efforts by critics of testing to reduce the volume of student assessments in schools, 22 percent of local education agencies in the FutureEd analysis plan to invest in the development or administration of student academic assessments, as they work to understand the extent of students’ learning loss during the pandemic.

Facilities and Operations

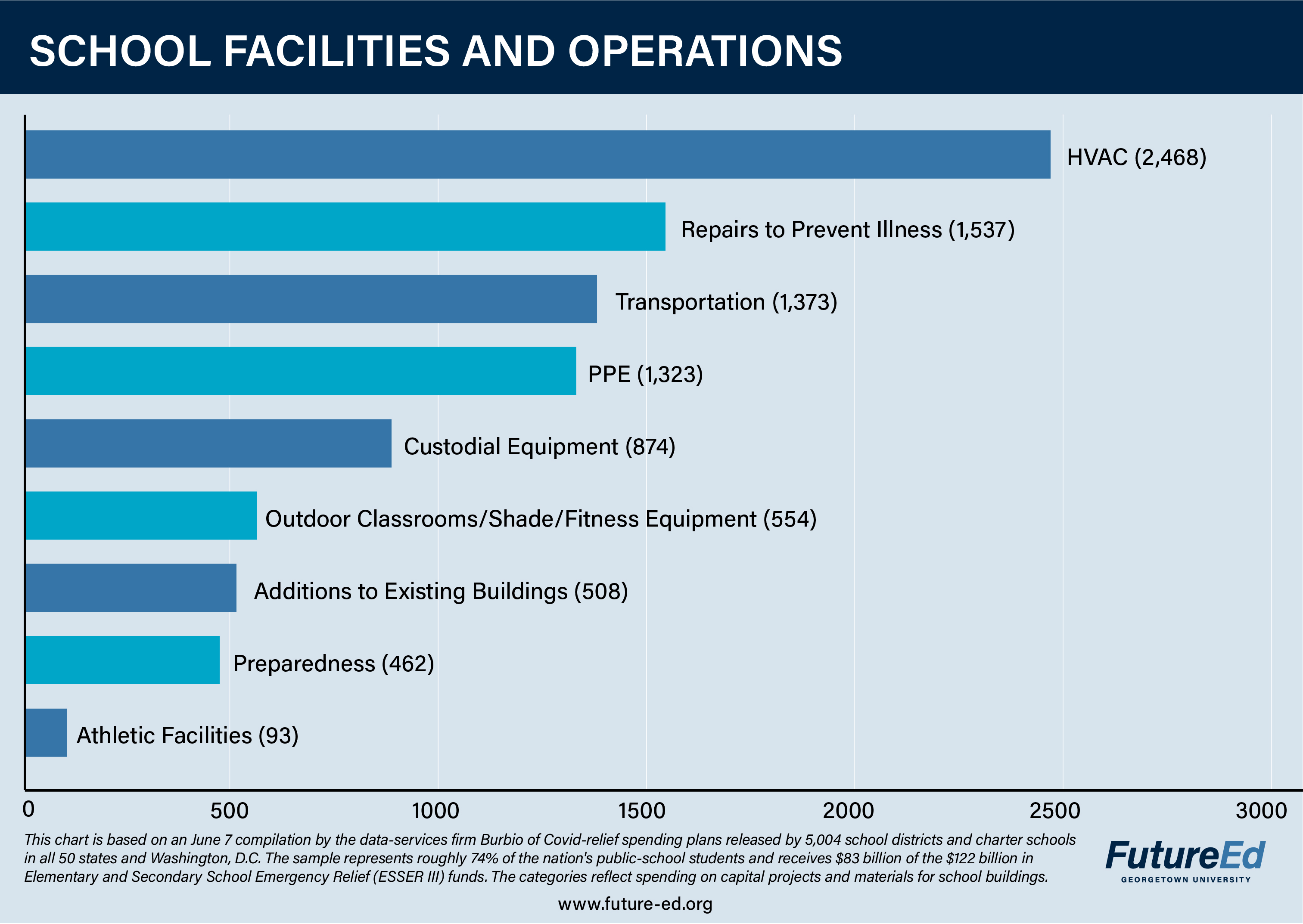

Among the most expensive priorities for school districts and charter schools is improving ventilation and upgrading heating and air conditioning systems. Nearlyhalf the districts and charters in the sample expect to spend money on school climate systems, and HVAC is a top-three priority in every region. The spending averages out to about $394 per student across agencies choosing this option. The plans range from thousand-dollar investments in filters that block the spread of the virus to multi-million-dollar plans for replacing entire HVAC systems. Los Angeles Unified School District, for instance, has budgeted $50 million of its $2.5 billion in ESSER III funding to provide 55,000 portable, commercial-grade air scrubbers for every classroom and commonly used room. St. Joseph’s School District in Missouri is budgeting its entire $25 million for HVAC upgrades. Such improvements are explicitly allowed in American Rescue Plan since they can not only prevent the spread of Covid, but can also guard against other airborne illnesses and provide a more comfortable climate for learning.

Among the most expensive priorities for school districts and charter schools is improving ventilation and upgrading heating and air conditioning systems. Nearlyhalf the districts and charters in the sample expect to spend money on school climate systems, and HVAC is a top-three priority in every region. The spending averages out to about $394 per student across agencies choosing this option. The plans range from thousand-dollar investments in filters that block the spread of the virus to multi-million-dollar plans for replacing entire HVAC systems. Los Angeles Unified School District, for instance, has budgeted $50 million of its $2.5 billion in ESSER III funding to provide 55,000 portable, commercial-grade air scrubbers for every classroom and commonly used room. St. Joseph’s School District in Missouri is budgeting its entire $25 million for HVAC upgrades. Such improvements are explicitly allowed in American Rescue Plan since they can not only prevent the spread of Covid, but can also guard against other airborne illnesses and provide a more comfortable climate for learning.

Mental Health

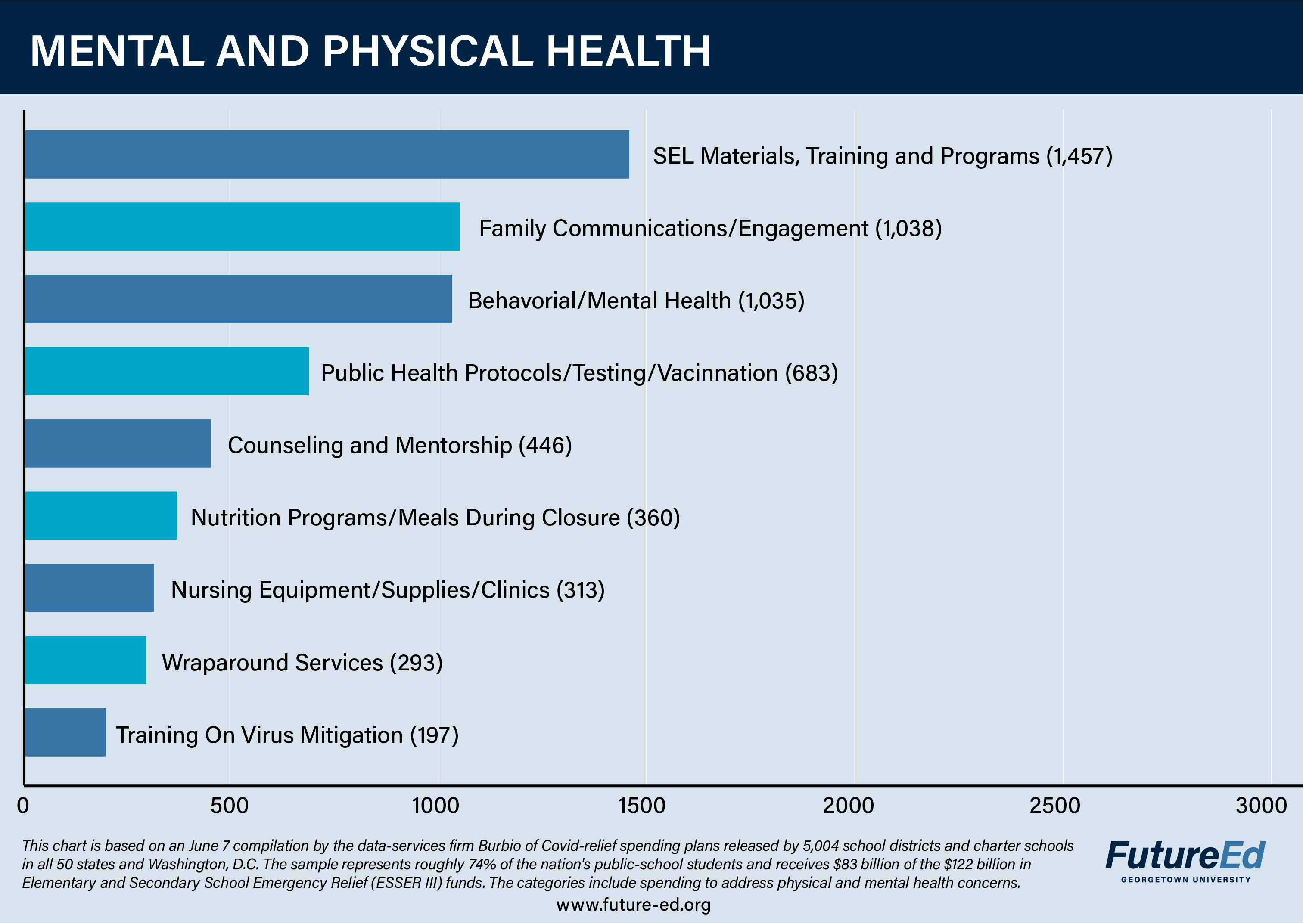

Helping students recover from the isolation and trauma of the pandemic is a priority in many local plans. About a third of local education agencies in the Burbio sample list social-emotional learning in their spending plans, including monies for curricula, classroom materials, and training, at an average cost per student of $84. Social-emotional instruction often focuses on helping students manage their emotions, relate to other students effectively, and develop strong organizational and study habits.

Helping students recover from the isolation and trauma of the pandemic is a priority in many local plans. About a third of local education agencies in the Burbio sample list social-emotional learning in their spending plans, including monies for curricula, classroom materials, and training, at an average cost per student of $84. Social-emotional instruction often focuses on helping students manage their emotions, relate to other students effectively, and develop strong organizational and study habits.

Additionally, more than a third of the sample, are hiring psychologists or mental health professionals. The priority emerges in other spending as well: about a quarter of the districts and charters plan to invest in behavioral and mental health initiatives and 9 percent list counseling and mentoring as priorities. Many districts are pursuing a combination of strategies: the Syracuse, New York, school district, for instance, expects to spend more than $1 million on social-emotional learning curricula, $3.5 million on intensive support for students and nearly $13 million on hiring psychologists, counselors and social workers.

Remote Learning

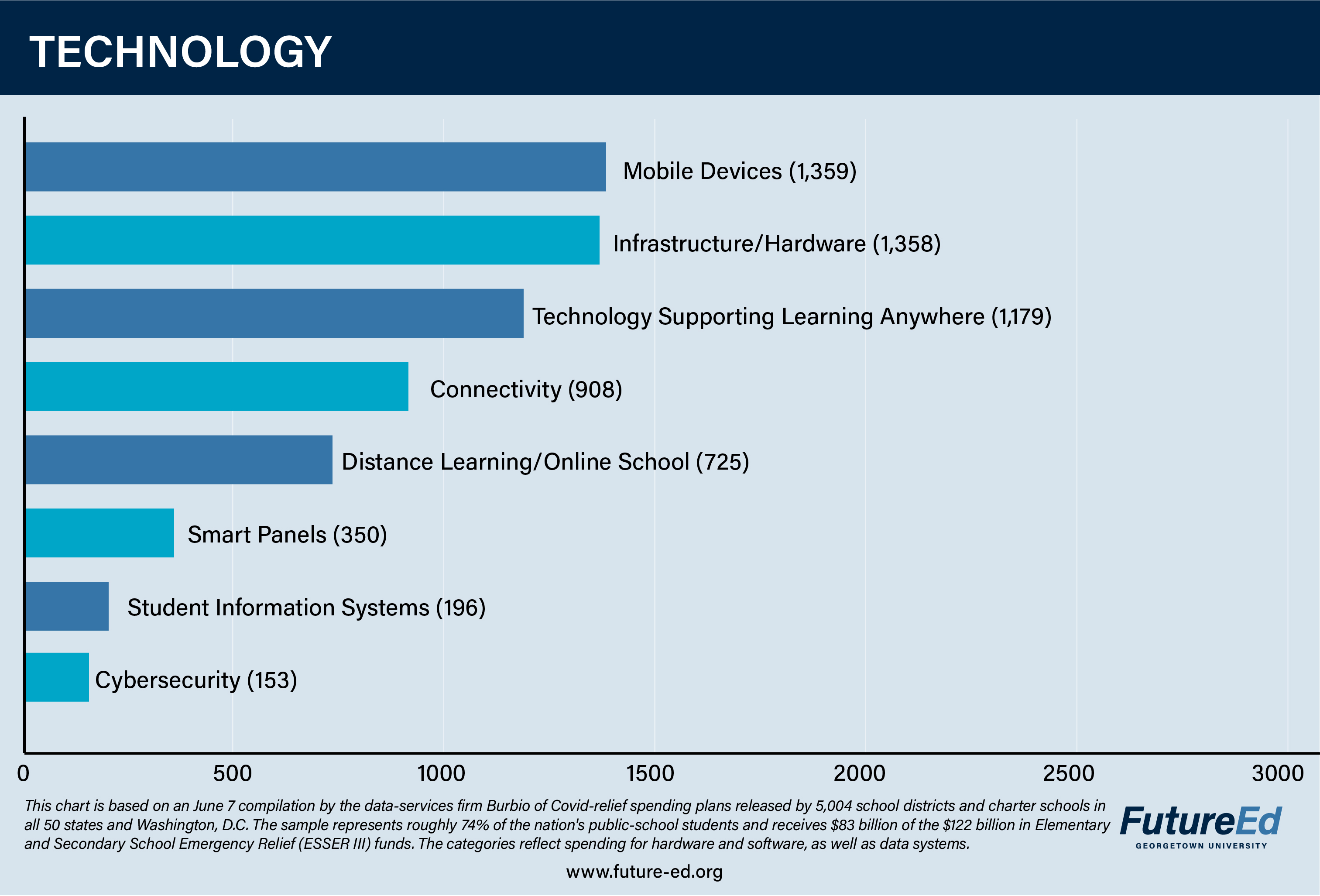

Remote instruction and technology remain key priorities despite the widespread return to in-person school. More than a quarter of the districts and charters in the Burbio sample intend to use American Rescue Plan funds on student mobile devices, and a similar share plan to pay for “technology that supports learning and enables students to learn anywhere.”

Remote instruction and technology remain key priorities despite the widespread return to in-person school. More than a quarter of the districts and charters in the Burbio sample intend to use American Rescue Plan funds on student mobile devices, and a similar share plan to pay for “technology that supports learning and enables students to learn anywhere.”

About 18 percent to invest in improving internet connectivity and 14 percent are spending on virtual models, online schooling or distance learning. Average spending on technology ranges from $68 per student for connectivity to $175 for mobile devices. The McAllen Independent School District in Texas is spending $16 million on mobile devices for its 22,000 students, and Milwaukee is spending $20 million for its 74,000 students.

With many school districts experiencing security problems when they transitioned to online learning during the pandemic, some are proposing to use federal aid to buttress their digital defenses, as allowed under Education Department guidance. The Miami-Dade County Public Schools in Florida, for instance, plans to spend $30 million, or $86 per student, on cybersecurity.

Regional Trends

The FutureEd analysis revealed both similarities and differences in local spending plans across the four U.S. Census Bureau regions. The Burbio sample captures about 26 percent of local districts and charters nationwide but a disproportionate share of the largest districts. It includes 41 percent of the local education agencies in the South, 24 percent in the Midwest, 23 percent in the West, and 18 percent in the Northeast.

The FutureEd analysis revealed both similarities and differences in local spending plans across the four U.S. Census Bureau regions. The Burbio sample captures about 26 percent of local districts and charters nationwide but a disproportionate share of the largest districts. It includes 41 percent of the local education agencies in the South, 24 percent in the Midwest, 23 percent in the West, and 18 percent in the Northeast.

Spending on teachers, counselors and academic staff emerged as the top spending priority across regions, with 56 percent of districts in the South and West and 64 percent of districts in the Midwest and Northeast planning to spend.

In both the Northeast and the South, summer learning was the second highest priority, with spending planned in 53 percent of districts in the Northeast and 51 percent in the South. HVAC spending was the third highest priority for both. After that the regions took markedly different approaches.

About half of the Northeast districts and charters planned to invest in professional development and more than 40 percent support spending on psychologists and afterschool programs. In contrast, nearly 50 percent of Southern education agencies planned to spend on software and instructional materials, with about 40 percent investing in professional development and transportation.

[Read More: With an Influx of Covid Relief Funds, States Spend on Schools]

In the West, ventilation, heating and air conditioning system upgrades was second one the list of priorities, with 51 percent of districts and charters planning to invest in such projects. Spending on professional development listed in nearly half the local agencies and psychologists in 42 percent.

The top three priorities were similar in the Midwest, with nearly 50 percent of districts and charters planning to spend on HVAC and about 40 percent on professional development. Summer learning came in fourth from the top in the West, with 45 percent of local agencies pursuing it, but did not appear on the Midwest list. Instead, about a third of Midwestern school districts and charters were planning to spend on employee benefits, instructional materials, technology expenses, and other facility repairs.

The FutureEd analysis found some instances of local spending priorities that seem at best only marginally, if at all, related to pandemic recovery. The Texarkana, Texas, school district is planning to spend $171,000 on band instruments. The school board in Burlington, Wisconsin, approved $100,000 to buy a 3D cadaver table for a high school’s anatomy course, allowing students to dissect virtual corpses via touch screen. Natchez, Mississippi, is hoping to break off $3 million of its federal aid to supplement a $34 million renovation of a high school and middle school.

But as a percentage of proposed Covid-response spending in the Burbio sample, such expenditures do not seem substantial. While spending on athletic facilities has garnered significant news coverage, for example, only 93 local education agencies in the 5,000-agency Burbio sample—less than 2 percent—are proposing to spend relief funds on athletics.

[Read More: Getting to Yes on Covid Relief Spending]

Importantly, much of the $83 billion covered by the FutureEd analysis has not been spent, the U.S. Education Department and state spending trackers show. Local agencies have until September 2024 to obligate the American Rescue Plan money that Congress approved in March 2021. School districts may change their spending priorities between now and then, and local leaders are undoubtedly going to face pressure from advocacy groups and commercial entities to direct ESSER funding in those directions.

Already, a North Carolina school district that had planned to spend $10 million on ventilation upgrades shifted the money to personnel bonuses in fall 2021 amid severe staff shortages. In Texas, two districts have had their Covid-relief funding withheld until they remove books from their libraries that some have found offensive.

The U.S. Education Department is tracking how much of the ESSER dollars have been spent in each state so far and shows only a small fraction committed so far. The department is asking states and districts for a more detailed breakdown on spending, but the release of such data would come more than a year from now. Some states, Georgia and Washington state, are publishing information on how districts are spending money. In several places they are grouping the data into eight or nine broad categories—and elicit some vague responses.

There’s an important role in the months ahead for state and federal regulators and local media to ensure that spending stays focused on helping students rebound from the pandemic. Ultimately, the effectiveness with which plans on local drawing boards are executed matters most.

[Find district and charter plans here]

Still, at this juncture, this snapshot of spending plans proposed by school districts and charter school organizations educating 74 percent of the nation’s public-school students provides valuable insights into the pandemic-response priorities of the nation’s local education leaders, and the collective plans provide a reason to be optimistic about the commitment to spending ESSER monies in ways that make a difference for students.

*Note: Tennessee local plans include funding from an earlier round of Covid-relief aid, and South Carolina uses a unique set of spending categories. When possible, we include data from the two states in the FutureEd analysis.

**Note: Georgia asked local agencies to combine spending on afterschool and summer learning into a single category, and many of the districts invested heavily in these priorities. Hence, when we calculated the average per-pupil spending on afterschool and summer programs combined, it jumped to $388, more than twice the average for afterschool and summer learning separately.

FutureEd Research Associate Gunjan Maheshwari provided research assistance for this analysis. Jackie Arthur designed the map and per-pupil spending chart. Merry Alderman Design created the five topic charts.